Estimated reading time 15 minutes, 41 seconds.

The Kitchener-Waterloo (K-W) area, about 90 kilometres southwest of Toronto, has matured into a global centre for technology and innovation. Tech companies are on a high in Canada, attracting funding and initial public offering (IPO) traction in hubs like K-W.

I take certain liberties with the K-W short form; arguably, it’s growing beyond the tri-cities of Kitchener, Waterloo and Cambridge, and is perhaps really a corridor extending back to Toronto.

Southern Ontario centres are among the most successful examples of fertile territory for the Canadian entrepreneurial spirit. BlackBerry and Research in Motion (RIM) are no longer the only big names to call the K-W region home.

Some believe the Toronto-Waterloo corridor has the potential to become Canada’s first technology supercluster. Local post-secondary institutions are generating graduates who may see being an entrepreneur, and a disruptive entrepreneur at that, as a viable out-of-the-chute career path.

You can feel the energy in the downtown area pubs, just listening, as I did.

I shamelessly admit the title of this piece spins off “Fightertown U.S.A.,” the colloquial name of U.S. Naval Air Station (now Marine Corps Air Station) Miramar, home of the flight school immortalized in the movie Top Gun.

I just don’t remember having seen a faster-developing sector of aviation, with greater potential for producing new jobs and growth–and frankly, more exciting–than unmanned aircraft (or “drones”).

Unmanned aircraft generally may include large aircraft similar in size and complexity to manned aircraft, all the way down to very small consumer electronics aircraft.

“Unmanned aerial vehicle,” or UAV, is another common term used today in conversation about drones. “Unmanned aircraft system” (UAS) or unmanned aircraft (UA) are terms perhaps used more often in the United States than by Canadians.

But we’re all talking about the same thing.

Drones are here to stay. They can perform hazardous work, like inspections of the normally inaccessible spaces of a nuclear reactor plant. In civil construction, they are used to survey sites and gather data for progress reports for investors.

The cost of maintenance inspections for tough jobs like wind turbines, hydro transmission lines and pipelines can be halved when compared to traditional means. Add in deliveries and airborne 3D printing repairs–the list of what is being done today is longer than we have room for here.

The global incremental opportunities for drones are seemingly limitless. Drones are set to revolutionize major industries such as mining, insurance, agriculture, infrastructure, and e-commerce.

Delivery by drone is a disruptive technology that may set new benchmarks for the traditional shipping business. A common theme in conversations with people who know this exploding industry well, is the growth seen in the last five years.

In 2016, consulting firm PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) estimated the global market for business services using drones at an astounding $127 billion.

FIRST-HAND EXPERIENCE

I spent some time recently taking the UAV ground school course at the Waterloo Wellington Flight Centre (WWFC), located at the Region of Waterloo International Airport (CYKF).

You could feed off the energy in the classroom, and it seems applications for drones in Canada are limited only by our imaginations.

A father-and-son duo in real estate plan to shoot their own aerial video for property listings, bringing a crucial marketing capability in-house instead of hiring someone to do it for them.

A man with his own roofing business wants to introduce thermographic imaging via drone to help with inspections. Another man from Environment Canada was exploring drone use for soil erosion surveys.

The most intriguing or unique idea was from a woman with a local conservation authority. They have a drone now and want to use it for such missions as looking for beaver dams and the associated damage, substituting a camera on a drone for slogging it on foot.

So why has K-W become such a hub for drones? To find out, Skies spoke with Sarah Spry, WWFC’s UAS business manager and one of its UAV ground school instructors.

“It’s a technology hub and such a talented pool of people,” said Spry. “And we’re close to Toronto. Communitech is here and helps tech start-ups. And, it’s a great quality of life here.”

K-W has an extremely high density of technology workers and start-ups, second only to California’s Silicon Valley.

Communitech was founded in 1997 by a group of entrepreneurs wanting to make Waterloo Region a global innovation leader. It has since grown into a public-private innovation hub helping start-ups grow and succeed, supporting a community of more than 1,400 companies.

WWFC’s UAV training works hand-in-glove with the flight school’s well-established fixed-wing pilot training. UAV training classes run once a month, and specialized courses are offered in conjunction with local community colleges at their request.

Real estate boards and insurance companies have also benefited from custom courses. Insurance companies are working to understand the industry. Companies and individuals providing home inspections are being trained to use drones, as some inspectors may have challenges with climbing.

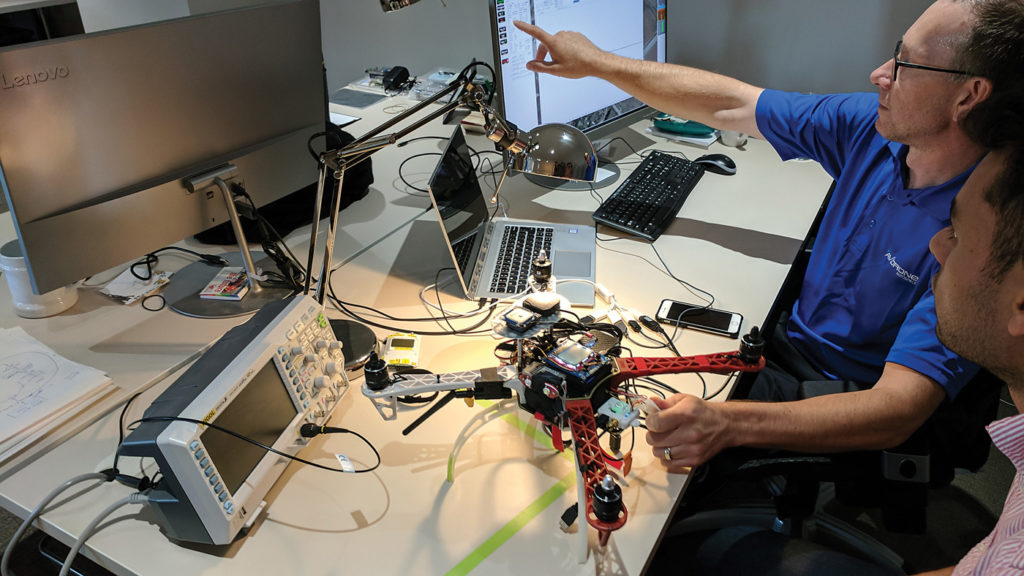

Skies spoke with Scott Gray, a K-W-based UAV entrepreneur and president and CEO of Avidrone Aerospace.

Avidrone recently moved its drone technology research and development offices and manufacturing centre to Chartright Air Group’s 50,000-square-foot Hangar 53 at CYKF.

Gray launched the company with his wife in 2007, designing and manufacturing fully-automated drone systems for commercial applications around the world. He moved into this from a mechanical engineering background and also spent time as a sponsored demonstration remote control model pilot.

Gray feels Avidrone’s niche is based on a few factors, including its proprietary flight control and autoflight system; range, efficiencies and control algorithm software; and the ability of Avidrone UAVs to lift heavier-than-normal and multiple payloads.

A current focus is on aerial delivery. A tandem-rotor UAV nearing completion in Avidrone’s final assembly hall can lift a 50-pound payload with arms that can fold down and grab a box.

It’s interesting that this particular model has a synchronizing drive shaft scheme, similar to that of a Boeing Chinook helicopter.

When asked about the possibility of having the good folks at Amazon deliver to your door, with you putting a big X on your front lawn to mark the spot, Gray predicted: “That’s the part that is a little far-fetched. More likely is delivery along predetermined corridors, hub-to-hub or hub-to-smaller hub. The driver is speed and often there are places where the trucks can’t go.”

Military applications are broad, too, and a consideration driving military planners is the fact a drone might be costly, but it’s ultimately expendable for missions in non-permissive environments.

Avidrone’s future lies in the provision of smart UAVs that don’t require such a high level of skill to operate. Gray also spoke highly of the help the Communitech hub provides in support and mentoring.

So, why K-W?

“It’s a cool place to be, and this is the view we have every day,” said Gray, gesturing at Chartright’s busy hangar.

Avidrone’s products are all custom-built to solve customer needs and specific missions, with turnaround times ranging from around six months to more than a year from agreed concept to delivery.

“We’re spending a lot of time talking customers through what can be done; the industry is still so new, there is no norm,” said Scott. “All these vehicles are tools to carry out a task.”

A turbine engine originally used as an aircraft auxiliary power unit (APU) rests on a pallet in the Avidrone shop, ultimately destined for a large-scale helicopter drone.

Another model has a spray tank fitted and can fly all day long, singly or as a swarm, along pre-programmed tracks to spray pesticide or other agricultural products. In these cases, the octocopter form of a UAV–which has become the common image in the media–makes sense because it doesn’t have to fly far or fast.

Scott said he could comfortably operate a UAV from the Region of Waterloo International Airport to Toronto autonomously, today.

What’s the strangest task for a drone operation he’s heard about?

“Carrying people,” said Grey. In other words: Uber by air.

FUNDING AND SUPPORT

There are other UAV players in the K-W area.

Skies also spoke with Bruce McPherson, dean of unmanned systems training at Clarion Drone Academy in Kitchener.

When asked the reason for the growth in this geographic area, McPherson said: “The politicians here really get it. The funding and support, it’s all here. And the people, the universities.”

He described typical clients participating in Clarion’s core training offering, saying: “Clients come to us either already operating commercially or needing to make a decision about whether to do so. After they train with us, we realize we can do more together. We often wind up assisting with things like developing standard operating procedures (SOPs).

“We walk them through the aviation side of what they are doing or are thinking about doing. And work to educate them that training isn’t just a one-time thing; rather, it is continuing education. We also would really like to work to bring more women into the industry.”

McPherson said they are happy to recently provide more First Nations students with UAV training.

Aeryon Labs, also based in Waterloo and previously profiled in Skies, designs and builds high-performance drones for military, public safety, and commercial customers around the world.

To have a look at the operations side, Skies was invited to observe a real-world mission, courtesy of UAV inspection services provider Industrial SkyWorks.

Five years in operation, this company provides the oil, gas and petrochemical industries and building owners with asset inspection drone technology solutions.

Skies met up with Industrial SkyWorks’ UAV pilots and thermographers, Chris Spagnola and Jordan McPhail, early one evening as they were setting up for a UAV thermal inspection of structures at the Highland Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant in Toronto.

When asked to describe the job that night, Spagnola said: “The client [a consulting engineering firm] has hired us to assess [within this project] over 700 buildings, taking still thermal images of the facades and roofs and doing some post-processing. What we actually do is stitch the individual images together to form a single large image. They are looking for any type of defect: cracked mortar, spalling brick, efflorescence. We’ve probably been here six or seven times and this will be our last visit [to this site]. Tonight we are doing rooftops.”

Both Spagnola and McPhail are bullish on Industrial SkyWorks’ BlueVu software.

“No one wants to go through thousands of images,” said Spagnola.

BlueVu, while not being used on this evening’s tasking, can automatically organize, analyze and select the most relevant images. When asked what else differentiates their company, both pilots stressed safety.

“They love the safety aspect,” said Spagnola. “They are huge on that. It’s giving them the opportunity not to go up on the roof. Just to give you an idea, we scanned 3.5 million square feet of roofing inventory in three hours.”

Previously, this might have taken three to four weeks of climbing on roofs with associated fall risk, doing this with handheld thermal imaging equipment.

Safety was clearly paramount for the flight operation itself as the drone takeoff and landing site was carefully prepared with pylons and flashing beacons in a parking lot outside the plant perimeter.

Preparation time was ample and allowed for powered paraglider enthusiasts in the vicinity to head home for the night, and for the winds to calm down.

A sustained wind speed of 40 kilometres per hour was the pre-set wind-warning limit for the Aeryon SkyRanger R60 UAS equipped with a thermal imaging camera. A thorough safety briefing by McPhail was followed by Spagnola’s pre-flight inspection of the drone.

No-fly zones had previously been programmed.

“We block off certain areas and we’ll also program a ring boundary where if we lost control it would have to stop,” said McPhail. “But we’ve never experienced that.”

Checklist completion and takeoff and climb-out to 75 metres looked ultra-smooth, with McPhail acting as pilot-in-command and Spagnola as the spotter, a typical arrangement with Spagnola in constant contact with McPhail, calling out clearance to roads, people, an active railway line and other areas to avoid.

Spagnola, as the spotter, had to ensure he always had the drone in sight as this was a visual line of sight (VLOS) mission. McPhail controlled the drone using a stylus and a tablet running Aeryon’s Mission Control Station (MCS) software.

Control of the drone was through a combination of manual inputs for altitude, heading and airspeed, via modem to the drone.

Dragging the drone icon to a pre-planned grid around the largest plant structure launched the autoflight segment.

Return to the landing site was manually controlled and equally smooth. A mission like this can last around 15 minutes and wrapped up with a check of the sensor’s SD card files on a laptop to ensure the imagery was captured.

“We were the first to get a night approval,” said McPhail.

The deliverable for the night’s work was a series of around 45 thermal images stitched together to form a mosaic.

REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

Make no mistake: Our regulator, Transport Canada, treats UAVs as aircraft. They are unmanned aircraft, plain and simple.

Changes are coming to regulations covering drone operations in Canada.

Transport Canada continues to work on developing the regulatory framework to ensure that drones will be used in a safe, secure and business-friendly way. Regulatory changes targeted to hit Canada Gazette Part II are expected to remove any remaining distinction between recreational and commercial use. When contacted by Skies, Transport Canada could not confirm a date for publication of the new regulations.

It’s anticipated there will be a minimum threshold centred on weight, below which operators can go fly and have fun. Beyond that threshold, it’s expected there will be delineation between simplified and complex airspace operations.

Simplified will simply mean, “stay away from an airport.” It won’t matter if the [airspace] is controlled or uncontrolled. The definition of built-up areas will go away, replaced by the restriction to stay 100 feet away from people not involved in the flying operation. This category will require a mark of 80 per cent on an online exam. Requirements for liability insurance will go away.

Complex operations will require passing a different exam and a practical flight test. The currently all-important Special Flight Operations Certificate (SFOC) may go away for the most part, with exceptions such as operations beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS), and extraordinary operations like dropping explosives.

SFOCs have been used in a somewhat random way up to now. Originally, they were meant to be used to document the approval of airshows and other special operations of manned aircraft.

Operators will be allowed to fly near an airport, still following all the necessary cautions, guidance and planning as with SFOCs. Drone registration is also likely on the horizon.

WHAT’S NEXT?

The final outcome of proposed new drone regulations for operations in Canada will to some degree pace the industry in the coming years. How the potential for an ADS-B Out mandate for Canada will affect drone operations remains to be seen.

Miniaturization of ADS-B Out avionics won’t likely be the determining factor. We’re already seeing ADS-B Out avionics developed that are small enough to be packaged inside a replacement position light for general aviation aircraft.

Transport Canada recently initiated a beyond visual line-of-sight (BVLOS) pilot project with multiple industry partners, to develop risk models. BVLOS will be pivotal to the expansion of commercial drone operations and a key to these operations will be viable detect-and-avoid technologies.

BVLOS has the potential to reinvent commercial drone operations, enabling data gathering, for example, over much larger areas without the pilot or the spotter needing to see the drone. We will need to trust the technology.

Lighter, longer-endurance battery development is a pacing item for further drone development and expansion of operational possibilities. Drone detection and warning systems for aircraft and air traffic control are under consideration.

An incident endangering the operation of a manned aircraft involving a drone is an offence under the Canadian Aviation Regulations. Penalties for violations include maximum fines of $3,000.

Insurance unknowns and privacy challenges are still to be addressed. A recent U.S. proposal would make encroachment over another person’s land by a UAS a form of trespassing that conveys a presumption of damages, so long as the altitude of the flight was 200 feet or below.

We’re witnessing a business re-spin as drone technologies shake up business models in sectors ranging from filmmaking to crop-spraying.

In the very near future, clients in all areas of the economy will begin to see the impact of drones on their operational processes–from the way they receive deliveries to how they interact with their insurers.

Norm Matheis is a freelance writer with extensive experience in the avionics industry.