Estimated reading time 10 minutes, 40 seconds.

Editor’s note: This story appears in the Skies special issue Aviation in the Face of Covid-19. Access the full issue here.

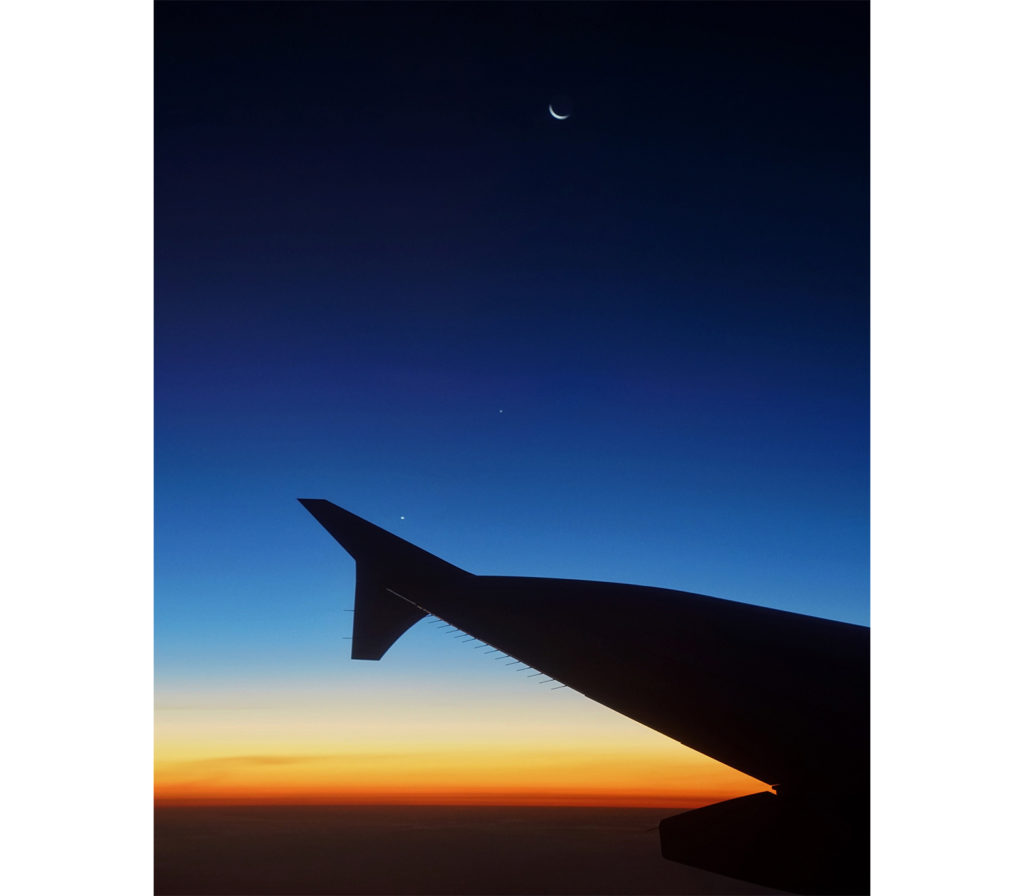

From the window of a commercial airliner, familiar icons scroll into view at an unhurried pace, like leaves floating down a lazy river. The Eiffel Tower creeps out from under the wing, the Seine snaking along beside it. Yosemite Valley materializes like a secret garden amid the vast, rocky terrain of the Sierra Nevadas, the mighty Half Dome a mere stitch in a quilt. Even the deep heart of the Grand Canyon — an easy get while flying between Denver and L.A. — can catch you by surprise at 35,000 feet.

People say they love window seats because of the view, but that usually means intermittent glances during lulls in the movie or while picking at meals with half-scale utensils. They’ll catch some clouds, patchwork farmland, and snowy peaks, along with the easy targets during departures and arrivals, like Manhattan or the Golden Gate. But they’ll miss the tougher targets, the pleasant surprises, and the insights — where things are, how they fit into the larger puzzle of geography, geology, and civilization.

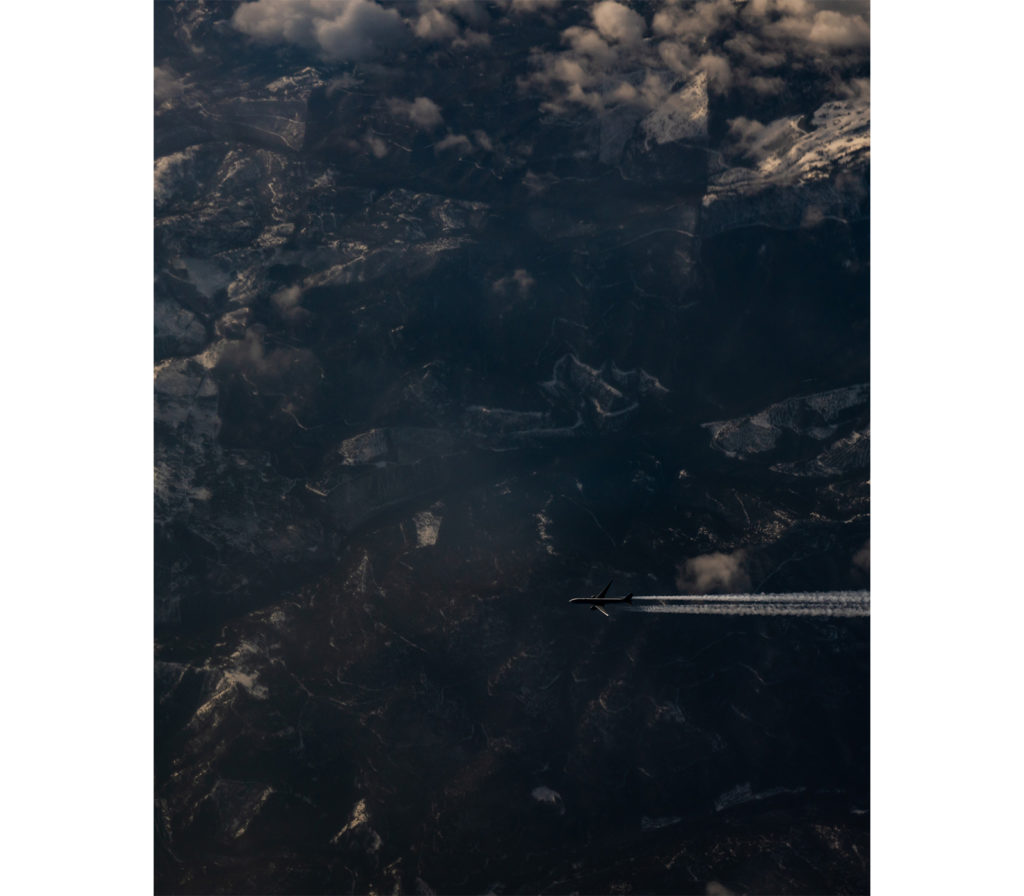

I learned on a flight from Frankfurt to Oman, for instance, that Bucharest, in Romania, is a buzzing metropolis and a labyrinth of massive, communist-era buildings mixed with modern skyscrapers. On another flight I saw that the glaciers of Greenland look like Play-Doh being extruded from a mould, which they kind of are. I spotted Monument Valley in a sea of buttes and mesas, watched the nighttime glitter of Seoul terminate at the darkness of North Korea, and noted that, at the equator, the crescent moon sits like a level bowl above the horizon, absent the tilt seen at more northerly latitudes. Approaching Ulaanbaatar, deep in Mongolia, and Dakar in West Africa revealed remote rural communities that I suddenly wanted badly to visit, to see what there was really like. You have to pay attention to really see the world you’re flying over.

I know this because aerial sightseeing — and window-seat photography in particular — has become my obsession while travelling. (All of the aerial photos accompanying this article were captured from the windows of commercial airliners.) While other passengers read, tinker with spreadsheets, or watch movies, I’m glued to the window like a man-child relic of the early Jet Age, gaping slack-jawed at the wonder of flight. I long ago gave up any hope of being productive in the air. Instead I keep two cameras ready, along with a large black rubber disk that sits on my lens and blocks cabin reflections in the window, and I just watch. If there’s Wi-Fi, my browser squats permanently at Flightradar24.com, where I track what I’m flying over and other aircraft in the vicinity — in case something interesting wanders by. I once snagged, over the Italian Dolomites, the private 747 of the royal family of the United Arab Emirates.

At the moment, of course, this pastime is on interminable hold — and the travel that enables it may never come back to what it was. All aspects of our lives are being impacted by the coronavirus pandemic, and air travel is taking a particularly hard hit. Companies that once flew their personnel easily and often might be more judicious about it as they rebuild their businesses. Vacations will be few and far between for travellers recovering from the sickening economic downturn. Airlines will have to rebuild, as well, a process that in itself might impact travel options due to overcrowding, limited routes, or, well, who knows what? This is completely new ground for everyone, and while we can count on people to want to resume exploring, interacting, and adventuring, it’s not remotely a foregone conclusion that life will be anything close to business-as-usual on the other side of this thing.

My own work, too, might necessarily shape-shift to something different, though I desperately hope that it will retain some semblance of my prior mobility. As a transportation, science, and technology journalist and photographer, I’ve enjoyed a years-long run of travel that routinely sees me top 150,000 miles per year in pursuit of innovations in these fields. Many groan at the prospect of such globetrotting, and I admit it can be draining as well as a challenge at home, but I also find it energizing and enthralling. It helps, of course, that I’m doing cool stuff out on the road — from reviewing new cars to visiting airplane factories — and often have the benefit of business-class accommodations, but even when flying in economy and toughing it out in long lines here and there, my infantile enthusiasm doesn’t wane. It’s weird, I know.

I’ve even grown to love the minutiae of air travel, its broader, time-skipping rhythms, and the bits that most travellers truly loathe, including airports and early departures. For me, a 3:30 a.m. iPhone alarm is, at worst, a summons to another possibly awesome view from above. Making it through security provides entrée to a comforting closed-loop of (mostly) clean and modern, steel-and-glass airport infrastructure, familiar shops and restaurants mixed in with one or two local options, energetic forward momentum, and, yes, the ever-present promise of interesting misadventure.

On a trip last year to Chile to see a solar eclipse, my flight into Santiago aborted its approach due to wind, hopped over the Andes, and landed somewhere in Argentina, where we sat for six hours on a taxiway before being cleared back to Santiago. I dozed, sat out on the “porch” of the mobile staircase, and goofed off with the crew while watching the sun rise. On the way back, the bonus views of the mountains were spectacular. I can be as crabby as the next guy as glitches stack up in transit, but I’ve found that being easygoing and open-minded greases the mental skids significantly.

This is true even when things go well. Despite my fastidious packing and prep — including a preflight checklist that’s as rigorous as anything that goes on in the cockpit, complete with routine self-pat-downs to ensure my phone, noise-cancelling earbuds, passport, and zippered, waterproof travel wallet are each still in their assigned pocket — I’m a remarkably chill boarder. I don’t get flustered, I have my app ready, and I’m unfailingly polite. I’ve seen enough people who haven’t been to know that being an angry jackhole or a disorganized hot mess while boarding only earns you well-deserved contempt. Besides, being nice to crew members pays off when, say, you want to change seats later because Mount Rainier is coming up on the left side of the aircraft instead of the right, as you’d planned.

In fact, if you want to grasp the true depth of my discombobulation at being so definitively grounded, consider the bonus prep I go through for each trip — including the careful selection of said seat for optimized viewing. Once a trip is on tap, I take a look at all the route options, including different stops. What points of interest do they fly over? What are the approach and departure paths for each airport? What are the time-of-day and aircraft options? That’s important: The 787 has magnificent windows, but the massive A380’s are like looking through a tunnel, and older aircraft windows can be scratched-up messes. Once I book the flight, I gauge which side of the airplane to sit on, and which rows I should target. Typically, all the way in the front is ideal — if I’m in business anyway — or all the way in the back. The goal is to only have the wing visible if I think it might be useful, such as when shooting approaches into airports and you want the lights on the ground to streak past the wing and engine.

I could go on, but suffice it to say that my prep extends all the way to travelling with little packets of glass-cleaning towelettes I can use if some gross traveller on a previous flight leaned on the window while dozing, smudging up the glass with his greasy hair. I also won’t bore you with details like camera settings and lens selections, though I can talk for days about those, too. The point is, my calendar is clear all the way through the turn of the next century, as most of ours are, and that’s left me fearful that this sliver of my life into which I poured so much effort and from which I drew so much pleasure might never return. My peripatetic inclinations — and my little side-hustle — must yield to the collective good.

I’m genuinely OK with that, as we all have far greater problems right now, myself included. But air travel brings something quite special to our lives — beyond the obvious speed of travel — that I, for one, have never taken for granted and which I miss greatly: The fact that these highly complex, utilitarian tools of commerce, which also happen to be highly sensitive to any sort of structural compromises, nonetheless come drilled with dozens of tiny holes along each side that exist for no other reason than to allow us to enjoy the view along the way.

Eric is a longtime transportation and technology journalist and analyst, a regular contributor to Wired, Popular Science, Gear Patrol, Forbes, and The Drive, and a professional photographer. Follow him on Instagram and Twitter at @EricAdams321, or visit his website.