Estimated reading time 9 minutes, 58 seconds.

When you step off the plane, it’s like you’ve landed on the moon. Your eyes have no perspective as they gaze at a stark white landscape that seems to stretch to infinity. The air is crystal clear and breathtakingly cold, without moisture, and the sun shines around the clock.

This is Antarctica in the summertime. And when you’re a pilot flying over that inhospitable but stunningly beautiful continent, it can feel like the last frontier.

“It’s up to the pilot to make a lot of the operational decisions down there,” said Brian Burchartz, co-founder and chief pilot at Oshawa, Ont.-based Enterprise Aviation Group. “There isn’t a whole lot of support. And of course, the snow conditions can be a problem. You can get a three-day storm where it’s blowing 50 knots. That’s when you really have to make sure the planes are tied down.”

Burchartz has been flying for decades, racking up more than 17,000 hours of flight time on various aircraft types, with more than 20 years of experience operating in polar regions.

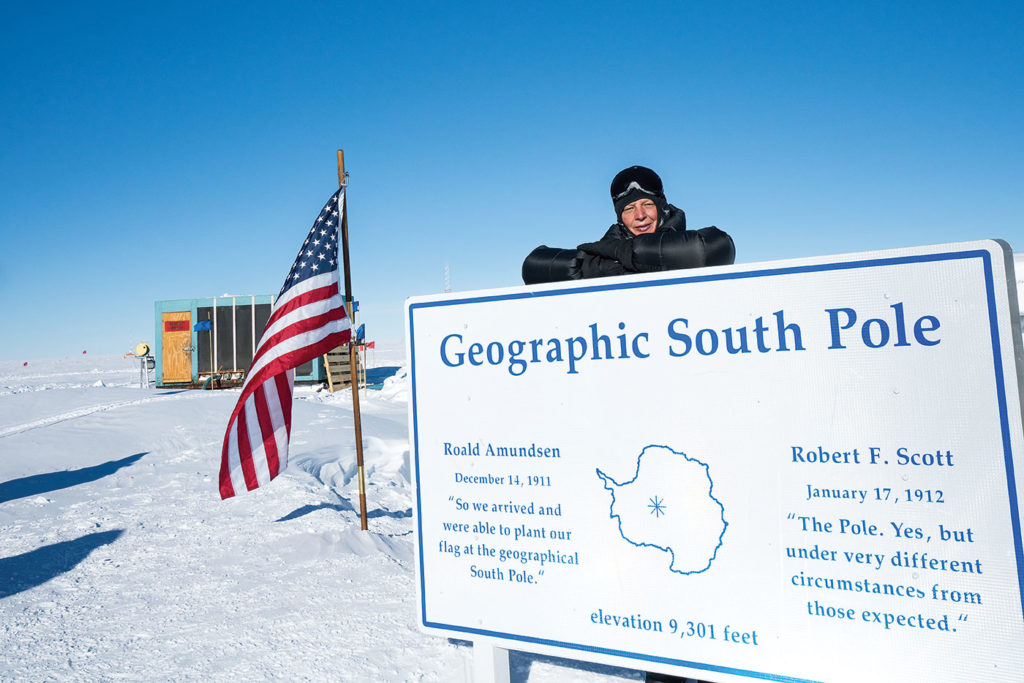

In March, he returned from his 11th season flying in Antarctica, the ice-covered land mass that is known as the home of the Geographic South Pole and Emperor penguins–and not much else.

Burchartz has been flying Douglas DC-3 aircraft for 33 years. A former employee of Skycraft Air Transport in Oshawa, he flew piston-powered DC-3s that hauled car parts for the nearby General Motors plant. When Skycraft closed in 1994, he and business partner Manny Rosario founded Enterprise that same year, picking up the expedited air cargo work for GM until things slowed down post-9/11.

“We then got involved with a tourism company in Antarctica, and operated a turbine DC-3 for them in 2001,” he recounted. “We started working for a few other companies down there; we’ve done 11 seasons there in total. The last couple of years have been with a company called White Desert.”

White Desert is a luxury travel provider that offers one- to eight-day excursions to Antarctica during the austral summer months (November to January).

Departing from Cape Town, South Africa, groups of up to 12 guests are flown on the company’s Gulfstream G550 jet to Wolf’s Fang Runway, a private 8,200-foot blue ice runway owned and operated by White Desert.

That’s where they meet Burchartz and his fellow crewmembers, who fly them to their camp. Guests are loaded onto an Enterprise-operated Basler BT-67–a beefed-up version of the DC-3 that boasts Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6A-67R turbine engines with Hartzell five-blade aluminum reversing propellers.

The characteristics that made the original DC-3 legendary–rugged construction, impressive short-field performance and admirable payload capacity–have been augmented by Basler Turbo Conversions of Oshkosh, Wis. The company improved upon an already good thing with the addition of several upgrades, including all-new avionics and electrical systems, the aforementioned turbine engines, a fuselage stretch with structural reinforcement, and an improved fuel system.

“The turbine DC-3 is really robust,” said Burchartz. “These planes were originally designed as bush planes and they are certified on skis, which makes them perfect for operating in Antarctica. Other than Wolf’s Fang, we need to land on skis pretty much everywhere else.”

The flight from Wolf’s Fang to the guests’ quarters at Whichaway Camp takes about 20 minutes. Situated on the coast beside a 200-foot ice cliff, the outpost consists of six double-occupancy luxury sleeping pods, about 20 feet in diameter, that contain a bed, writing desk, wash area and toilet.

Whichaway also offers shower and kitchen pods, as well as lounge and dining room structures. The camp operates according to strict environmental guidelines to minimize its impact on the environment.

Adventurers wanted

At eight days in length, White Desert’s signature US$92,500 excursion includes two big highlights: a visit to the Geographic South Pole and a 2.5-hour flight from camp to Atka Bay to see more than 6,000 majestic Emperor penguins and their young chicks.

“We do two flights for them. The South Pole flight is a two-day trip with a stop for fuel on the way back. We get rest there and continue back to Whichaway the next day,” said Burchartz.

That “night”–the continent is bathed in 24-hour sunlight at that time of year–is spent in small tents pitched on the Antarctic Plateau, where guests exercise their adventurous spirit while dining on rehydrated food. The experience is not for the faint of heart, with temperatures at the South Pole averaging -30 C in the summer months when tours are operated.

Burchartz and the other pilots are used to sleeping in tents, however. During the Antarctic tourism season, they camp out at Wolf’s Fang, where conditions are decidedly more basic than at Whichaway.

“It does take a bit of getting used to,” he said. “We stay in little mountain tents and there is a mess and lounge. There is no Internet. We have occasional email through a sat phone, so it’s quite limited.”

The Wolf’s Fang camp is home to about 12 people, including pilots, a cook and two aircraft maintenance staff. There is no hangar to shelter the planes, so inspections must be done outside in the open air–hopefully on days that are less windy. A Herman Nelson heater is used to warm up the tools.

When bad weather does roll in, crews hunker down and pass the time reading books, watching previously downloaded movies, listening to music, and catching up on sleep.

But the isolation doesn’t seem to bother Burchartz, who told Skies he enjoys Antarctic flying.

This year, he said the weather at Wolf’s Fang was quite good and none of the excursions were cancelled. For this season, the Enterprise team had one leased BT-67 on site as well as a backup DHC-6 Twin Otter leased from Yellowknife, N.W.T.-based Summit Air.

“We have to fly the planes down, and that takes about a week to get there. We go through South America to Punta Arenas [Chile], and make our way around to our base at Wolf’s Fang.”

He said that two BT-67s will be needed next year to handle planned White Desert expansion, especially because a Twin Otter doesn’t have the range to do the South Pole excursion.

Diverse operation

In addition to its work in Antarctica, Enterprise Aviation Group operates several divisions from its headquarters at the Oshawa Executive Airport (CYOO), including a fixed-base operation (FBO) and Durham Flight Centre flying school.

The company’s approved maintenance organization (AMO) services a wide variety of aircraft, among them the Beechcraft King Air, Douglas DC-3 and Basler BT-67, de Havilland DHC-6 Twin Otter, Piaggio P-180 Avanti, Pilatus PC-12, Dassault Falcon 10, Falcon 20, Falcon 50, Falcon 900, and smaller piston-powered planes. The AMO also holds ratings for avionics, components and sheet metal structures.

Aircraft charters are available on Enterprise’s Dassault Falcon 10 business jet or Beech King Air 90 turboprop.

The company also offers private aircraft management services, including managing three Basler BT-67s for Bell Geospace. Often, it is one of those aircraft that is flown to the South Pole for the White Desert contract.

In total, Burchartz said Enterprise employs about 40 staff members and operates 15 aircraft, including those at the flight school.

But although the company is incredibly diverse, he still prefers flying in Antarctica. This year his son, Cullen Burchartz, joined him.

At age 24, Cullen has about 600 hours on the BT-67 and 1,600 total hours. For someone who has been hanging around the airport as long as he can remember, it was a thrill to ship out to Antarctica last year when a second crew was needed.

This year, he went down for a full season, leaving Nov. 16, 2018, and returning on Feb. 2, 2019.

For a young person accustomed to today’s uber-connected world, Cullen said working in Antarctica was a strange experience.

“It was kind of neat but definitely weird for the first while,” he said. “It’s interesting. You’re not on your phone. There is no Internet. Sometimes you just accepted it, the boredom. You could go out cross-country skiing and try to help out around camp. But once the chores are done, you’re just sitting around.

“One thing I did find out is that Spotify accounts stop working after 30 days of not being connected!”

Crews at the Wolf’s Fang camp do get over to Whichaway for occasional meals and showers, but for the most part they are roughing it.

While it’s definitely not for everyone, Burchartz told Skies he enjoys Antarctic flying.

“You’re in control. It’s the scenery, and the people you work with. It is like flying the last frontier.”

Beautiful plane. I have more than 6500 hours in Douglas DC3 (16000 in total) …. If you are interested in an experienced pilot …. you can write to me at vicentefuentesgonzalez@gmail.com. I live in Miami, Florida.