Estimated reading time 14 minutes, 53 seconds.

At 11 a.m. on Sunday, Sept. 3, 1939, the citizens of Great Britain were gathered around their radios as a humbled British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain told them that “… this country is at war with Germany” and then, somewhat selfishly, “You can imagine what a bitter blow it is to me that all my long struggle to win peace has failed.”

In 1939, newspapers did not publish on Sundays, so most Canadians would not learn the details until city broadsheet papers hit the streets on Monday. Though no one would know it then, the war had already claimed two Canadians — both pilots with the Royal Air Force (RAF).

Just four hours after Chamberlain’s broadcast, Pilot Officer Ellard Cummings of Ottawa, a boyish and recently winged pilot in the RAF, was ferrying Westland Wallace K6028, a target tug of No. 1 Air Observer School, from Aberdeen to RAF Evanton through Scottish fog, when he slammed into a granite peak in the Bennachie Hills. He and his air gunner, LAC Ronald Stewart, were killed instantly — the second and third Allied servicemen to die in the war. (The dubious honour of being first went to Pilot Officer John Isaac, whose Bristol Blenheim crashed near RAF Hendon two hours before.)

Cummings was the first Canadian to die in the war, and his mother Edith would be the first of more than 45,000 Canadian mothers to suffer the loss of a child to the war in the next five years.

At 4 p.m. on Monday (11 a.m. EST), with the war just one day old, five Blenheim bombers of the RAF’s No. 107 Squadron lifted off from RAF Wattisham, bound for the North Sea coast of Germany. They were to attack the German pocket battleship Admiral Scheer and cruiser Emden, reported anchored at Wilhelmshaven. Of the five, only a single Blenheim would make it back. One of the four shot down was piloted by Sergeant Albert Prince of Montreal. He managed to ditch his aircraft and though all three crew members got out, he died of his wounds.

The deaths of these two Canadians would be largely lost in the media blizzard that surrounded the declaration of war and the same-day torpedoing of the liner SS Athena northwest of Ireland. Before the week was over, Canada issued its own declaration of war, and soon Canadians would hunger for news of their countrymen in the fight.

With the Royal Canadian Air Force in the throes of expansion and training, no Canadian fighter unit would be dispatched to Europe for nearly nine months. In order to show folks on the home front that Canadians were indeed fully engaged in the war, it was decided, as a public relations effort, to bring together Canadian pilots who were already serving in the RAF into one squadron — 242 (Canadian) Squadron. The squadron was formed in late October 1939, but only converted to Hawker Hurricane fighters in February of 1940. It would be in training or flying convoy patrols until the beginning of the Battle of France. A detachment from the squadron deployed briefly to France and Belgium in May, then returned to England in time to participate in the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force at Dunkirk. At the beginning of June, the squadron was back in France where it suffered heavy losses before leaving in haste ahead of the advancing German army.

In England, the squadron licked its wounds and prepared for the start of what would soon be called the “Battle of Britain.” By the beginning of the “Battle,” the squadron had a new commander — Douglas Bader, the inspiring and legless fighter pilot known for his tenacity and leadership. The number of Canadians in the squadron had by then declined, but there were still several outstanding fighter pilots among them, including the irascible Stan Turner of Toronto (then with seven victories of his final total of 15), and the enfant terrible of No. 242, Willie McKnight of Calgary. McKnight was, by then, already a double ace with 10 confirmed victories, and Bader recognized his aggressive spirit and talent, routinely having him as his wingman.

McKnight scored three victories on Aug. 30 and a further two on Sept. 9, making him a triple ace by the end of the Battle. Squadron Leader The Reverend Guy Mayfield, Anglican Chaplain at RAF Duxford during the Battle of Britain, would write of McKnight in his wartime diary: “MacKnight (sic) was short and wiry and tough. If anyone had asked me what a typical pilot of [F]ighter [C]ommand was like, I could not have done better than to introduce MacK.” McKnight would disappear on a patrol over France in January 1941.

In June, RCAF No. 1 (F) Squadron arrived in England with their Hurricanes and set to work getting ready for the coming battle. By mid-August, the squadron was operational and joined the fray. In all, 27 Canadians posted to this squadron took part in the battle in the nearly two months it was active. Several squadron pilots are worth noting. Squadron Leader Ernie McNab of Rosthern, Sask., the squadron’s commanding officer, was the first member of an RCAF squadron to claim a victory. Hartland de Montarville Molson, the Montreal brewery scion, would go on to command two different fighter squadrons back in Canada and Arthur Nesbitt, also of Montreal, would later command wings in the Aleutians and in Europe. After the war, he helped create Canada’s largest investment bank, now BMO Nesbitt Burns.

Canadian pilots accounted for 194 Luftwaffe losses during the Battle. The top Canadian was Flight Lieutenant Mark “Hilly” Brown of Portage La Prairie, Man., Canada’s first air ace of the Second World War with a total of 15 victories during the Battle of France and Battle of Britain flying with 1 Squadron of the RAF. At 39, the oldest Canadian pilot to take part was Flight Lieutenant Gordon McGregor of Montreal, whose score was 5.5 enemy fighters. Retiring as a Group Captain, he is also remembered as the future inspired leader of Trans Canada Air Lines. The youngest Canadian pilot in the Battle, Leo Ricks from Calgary, was just 19 years old when he flew with 235 Squadron, RAF.

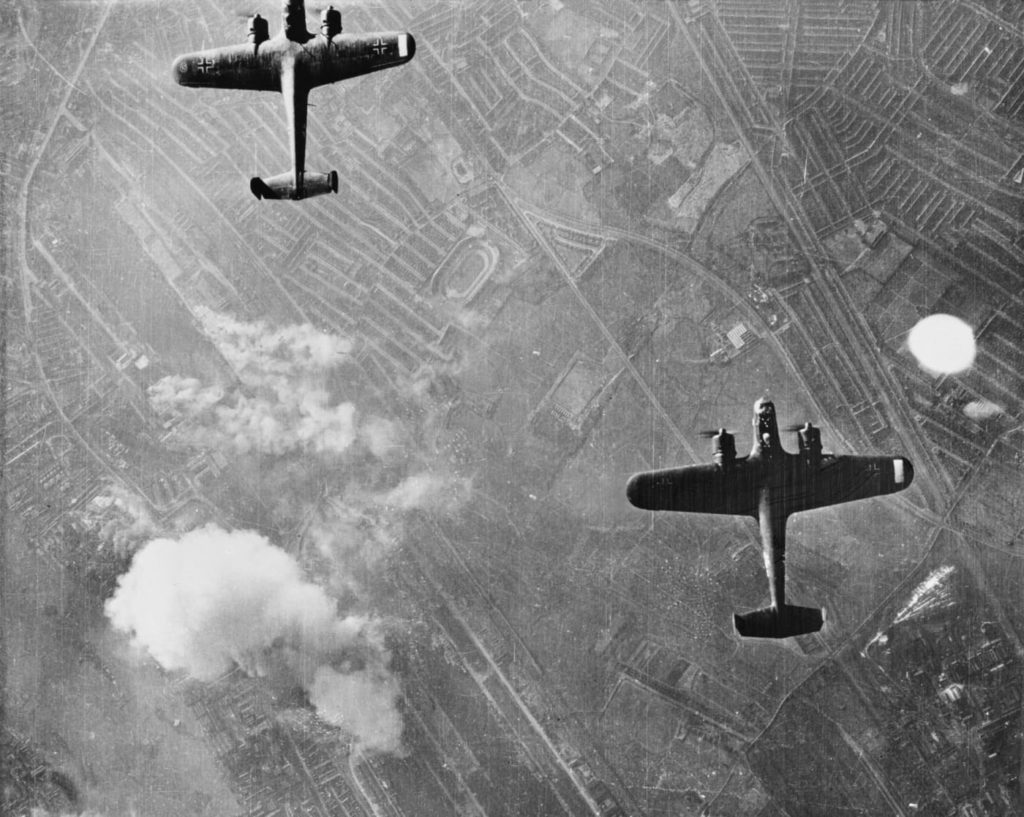

On Sunday, Sept. 15, 1940, the day Great Britain and the Commonwealth now celebrate as Battle of Britain Day, the Luftwaffe launched its largest and most concentrated aerial attack to date on London and Southern England. This day is widely considered to be the climax of the Battle itself, and though it would wind down slowly over the next month and a half, the Luftwaffe would never again attack in such numbers.

Perhaps the defining moment of that day’s aerial combat (and perhaps of the entire Battle of Britain) was the very public downing of a Dornier Do 17 bomber that was swarmed by Spitfires and Hurricanes from several squadrons. The aircraft would later be credited to Sergeant Ray Holmes, an English Hurricane pilot who, after running out of ammunition, rammed the Dornier from behind, cutting off its empennage and sending it spiralling out of control. Shedding its wings, it plummeted vertically and crashed onto the forecourt of Victoria Station, while thousands of people watched from below.

One of the pilots who helped bring it down was Ottawa native and ace Keith “Skeets” Ogilvie of 609 Squadron, RAF. Gun camera film from his Spitfire clearly shows large components of the Dornier breaking away as he hosed it with his machine guns. Charismatic, scrappy and good looking, Ogilvie, who would later sit for RAF portraits by famed photographer Cecil Beaton and war artist Cuthbert Orde, had a penchant for showing up at key moments — he was the last man out of the tunnel known as “Harry” in the Great Escape. Luckily, he was not among the 50 recaptured airmen who were executed.

Of the 574 foreign pilots who are listed on the Battle of Britain Monument in London, 111 were Canadian, with 22 killed in action (including one Newfoundlander) during the battle — 18 with the RAF and four with the RCAF. A further 36 would not survive the war. Their legacy, however, was much more than the competent and aggressive fighter pilots they most certainly were. Theirs was ultimately to be a story of inspiration and leadership.

Young boys coming of service age in the first years of the war were fuelled by newspaper stories and newsreels depicting heroic Canadians flying Spitfires and Hurricanes, standing up for what was right and saving Britain from Nazi domination. They flocked by the hundreds of thousands to recruitment centres across Canada dreaming of wearing the dashing blue RCAF uniform and flying a Spitfire. The majority of Canadian combat pilots and airmen who would risk their lives with Bomber Command, Fighter Command and Coastal Command, who participated at D-Day or who fought the Germans, the Italians and the Japanese to their knees in theatres of war around the world, were inspired to do so because of the courage and sacrifice of those 111 Battle of Britain pilots.

Later, several of these pilots would find themselves leading fighter squadrons during the Siege of Malta — another protracted and strategic aerial conflict rivalling the Battle of Britain. Mark “Hilly” Brown, Canada’s first ace, would lead the wing at Malta in the early stages of the siege, but was eventually killed in action over Sicily. Robert “Butch” Barton of Kamloops would lead 239 Squadron, RAF on Malta; and while in India after the war, helped to found the Pakistan Air Force.

Many Canadian fighter pilots who survived the Battle of Britain would go on to lead squadrons and wings in the RAF, as well as the rapidly-expanding RCAF, as the war grew to global proportions. Thirteen pilots, including Edwin Reyno, Hartland Molson and Ernie McNab, would return to Canada to command one or more of the 37 RCAF squadrons of the Home War Establishment. These squadrons were created to protect Canada’s coasts, but were also the pipeline training ground for fighter pilots who would eventually see action in North Africa and Europe.

Ed Reyno (a relative of Skies publisher Mike Reyno) would rise in rank to Air Marshal and help lead the post-war RCAF. A further 12 would command frontline RCAF squadrons in Malta, North Africa, Europe and as far away as Gujarat, India, while 10 others would go on to command fighting units with the RAF. Seven, including highly respected leaders such as “Johnny” Kent, Stan Turner, Arthur Nesbitt and Dal Russell, would lead entire fighter wings in the coming years.

The strength and fighting spirit of any squadron comes from the top down. The willingness to press attacks aggressively and the skills needed to survive are taught by flight, squadron and wing leaders, whose experience in battle is fundamental to the success and safety of the airmen under their command. There is no doubt that the Battle of Britain was a crucial victory, but it was also, and perhaps more importantly for Canada, the furnace in which the core of experienced, courageous and motivated leadership of the future RCAF was forged.

Fighting tenaciously and dying violently alongside their British counterparts in the Battle of Britain won Canadian pilots the professional respect of the RAF and a firm footing in the command structure under which future Canadian squadrons would operate. It also won them the eternal gratitude of Britons.

On Sept. 15 (Battle of Britain Day), Flying Officer Ross Smither of London, Ont., a Hurricane pilot with 1 Squadron, RCAF was shot down and killed near London. In a heartfelt letter to his parents, the squadron chaplain described the details of his funeral: “… During the morning, the sun shone brightly, but as we entered the funeral service it seemed that the heavens over England could not contain their weeping, and the rain came.”

Great piece of work on the proud and professional Canadian fighter pilots of the RCAF and RAF. And not to be forgotten should be included with Hilly Brown and the Battle of Malta “George Frederick “Buzz” Beurling, DSO, DFC, DFM & Bar (6 December 1921 – 20 May 1948) was the most successful Canadian fighter pilot of the Second World War. Beurling was recognised as “Canada’s most famous hero of Second World War”, as “The Falcon of Malta” and the “Knight of Malta”, [1] having been credited with shooting down 27 Axis aircraft in just 14 days over the besieged Mediterranean island.” Credit Wikipedia