Estimated reading time 13 minutes, 49 seconds.

When Dave Olesen goes flying, his basic survival kit is always right in his flight coverall.

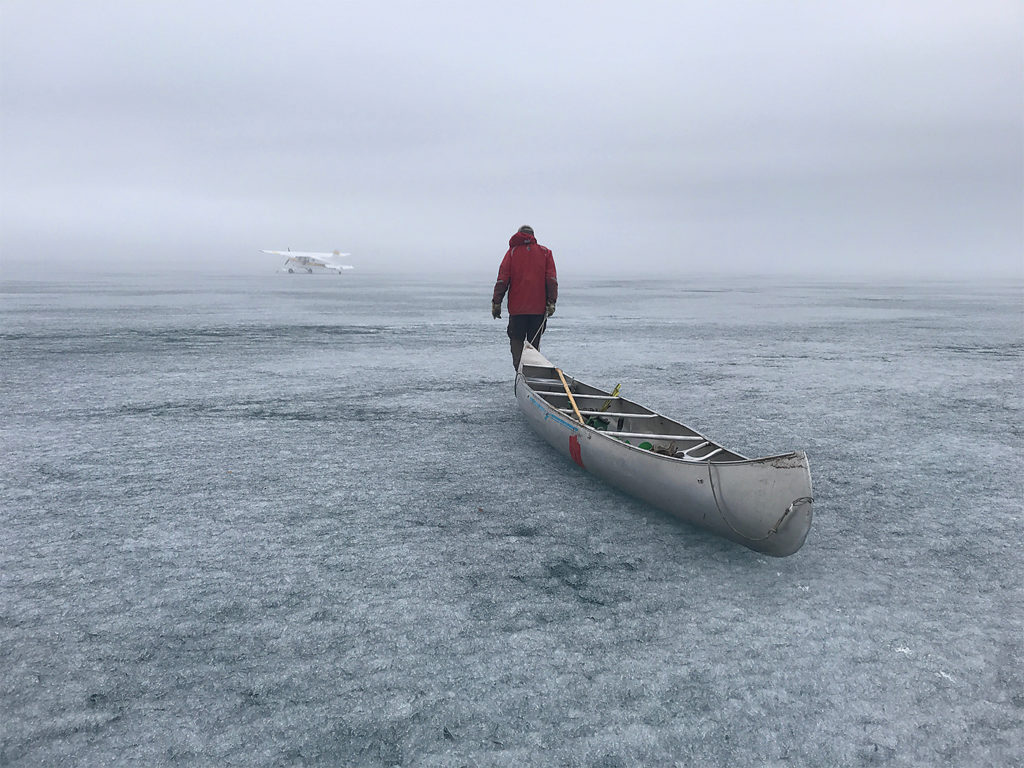

Before he takes off in his single-engine Aviat Husky or Found Bush Hawk, he stuffs his pockets with the necessities of life: waterproof matches, a lighter, string, pliers, a belt knife, signal mirror, water and a compact survival blanket. In the back of the plane are an Arctic tent, food, campstove, a rifle, snowshoes and a snow shovel.

A southern pilot might wonder why so much gear is necessary. But if they were to take off with Olesen from his remote home base on McLeod Bay at the northeastern tip of Great Slave Lake, they’d immediately understand. Once he is out over the tundra two hours or more to the north and east of home, a GPS query for “nearest airport” come back as “none.”

Olesen – whose company, Hoarfrost River Huskies, offers northern air charters and dog team expeditions – knows that his own safety and that of his passengers depends on being prepared for an unexpected campout.

Since 1987, he and his wife, Kristen, have carved their homestead into a starkly beautiful plot of land on the bay at the mouth of the Hoarfrost River. Their home is 265 kilometres (165 miles) northeast of Yellowknife, N.W.T., as the raven flies, and 337 km (210 miles) by lake from the nearest highway.

The couple raised their two daughters there, home schooling them in not just academics but wilderness living as well. Nowadays, the girls are off at university and work and Hoarfrost River is home to just Dave and Kristen and their 30 sled dogs.

Born in Illinois, Olesen became a dog musher in the 1970s and was drawn to the Canadian North. He participated in expeditions across the top of Canada, from Yellowknife to Baker Lake, Nunavut, and up the coast of Hudson Bay.

Olesen immigrated to Canada in 1987, chucking his jobs as pilot and guide in northern Minnesota, and cashing it all in to buy the Hoarfrost River property.

Just to be there

“When I first came north, aviation was simply a way to move us around,” said Olesen, who came to the N.W.T. with a 1946 Piper Cub. “It was an old-time airplane. People looked askance at me – ‘Who is this guy?’ ”

Kristen joined him in 1989 and by 1992, the region was in the thick of the diamond rush.

By then, the Olesens had become good friends with Peter and Teri Arychuk, co-founders of Yellowknife-based Air Tindi. The company had recently acquired several Twin Otters to support mining exploration in the region.

“Peter and I were dog sledding to town one December night and he said, ‘Come and fly in the right seat of a Twin Otter,'” recalled Olesen.

He flew as a co-pilot for two summers, before buying an Aviat Husky in 1994.

“I just wanted to continue an outfitting business and racing sled dogs. I was convinced that if I bought it (the Husky), they (Air Tindi) could operate it in their fleet. It became a really good thing.”

The Husky was an attractive and cost-effective option for wildlife surveys and geological exploration. Olesen flew it under the Air Tindi banner until 2005.

In 2006, he and Kristen decided to launch their own air operator business and base it from their home at Hoarfrost River. Their location on Great Slave Lake meant that fuel and other heavy shipments could arrive by water.

“Over the years, two things have become obvious to us,” Olesen told Skies. “One, you can in fact base a charter business at the Hoarfrost; and two, if you really want to grow that charter business and jump in wholeheartedly, you’d need to move to Yellowknife.”

For the Olesen family, the answer was simple.

“Our take has always been that aviation is the thing that allows us to live where we live. Our years there have been all about being out there – a bigger charter business is a workable dream, but it’s not our dream.”

Making it work

Olesen, 62, is the textbook definition of “bush pilot.” He’s an outdoorsman who is more at home staking out a tundra wolf den with a researcher than sitting in a meeting room at The Explorer Hotel in Yellowknife, where he spoke with Skies.

Aviation has always provided the family’s bread and butter, and Olesen hires out for a variety of missions. One day he might be gathering lake sediment samples; the next, he could be flying over a herd of caribou with a wildlife biologist.

Between them, Olesen’s two aircraft fly about 700 hours a year. That includes many 4.5-hour ferry flights for maintenance, which is done at Tim’s Air Maintenance in Fort Nelson, B.C.

“If we can do about 550 revenue hours between the two planes in a year, we’re fine,” said Olesen. “The biggest headache over the years has been maintenance logistics. If I could do it all over again, I would get my AME [aircraft maintenance engineer’s licence] as well as my pilot licence. On the other hand, it’s really good to have an outside set of eyes on your aircraft.”

Both of his planes are equipped with tundra tires or wheel skis and operate from the ice or a sandy landing strip until mid-June, when Olesen flies his aircraft to Fort Nelson to have the floats installed. A mere three and a half months later, it’s time to equip for winter all over again.

Hoarfrost River Huskies still relies on the Olesen family’s passion for dog mushing. Both Dave and Kristen were “hard-core” mushers back in the day, training and competing in the Iditarod, the Yukon Quest, and other big races.

“We’ve continued to have dogs and do some guiding and outfitting,” he explained. Through connections to the University of Alberta and Wilfrid Laurier University, the Olesens welcome a class of students to their homestead in winter. Half the class sleds out to the tundra with Olesen for a week while the other half stays at Hoarfrost River to work on academic credits – then they switch.

Sometimes, the temperature during those trips drops to -50 C (-58 F). Students sleep in expedition-type tents equipped with woodstoves. “Two mornings while they were out in 2018, we were the coldest spot in the country,” recalled Olesen.

Quiet skies

These days, Olesen wonders about the future of bush flying. He said the skies and the VHF radio are “eerily quiet” on any given day.

“The biggest challenge nowadays is being out there without a lot else going on,” he added. “I can get this nervous feeling. The other day, I was up northeast of Bathurst Inlet dropping off supplies in the Husky. If something even minor goes wrong, you know it’s going to be a big headache. I’m not terribly worried nowadays about being rescued, since Kristen is tracking the plane, but more uptight about getting fixed, way out there.”

If you fly, it’s a given that your aircraft will eventually be grounded. Repairs might be simple close to urban centres, but they present a big logistical challenge at and beyond Hoarfrost River.

“When things happen, it basically costs you a pile of money,” said Olesen. “I’ve bent a prop, blown a cylinder, and once had a broken ski axle. That little ski part was just $500, but it had to come from Ontario and then we had to get it to the plane, which was way out on the tundra. These are not things you claim from your insurers. You just fix them.”

That last repair ended up costing the Olesens over $10,000. They had to hire other aircraft to fetch the passengers who had been on board, get Olesen back to base, and then to meet up with the mechanic, fly back in, install the part, and finally get everybody back to where they started.

“Early on in our years of running on our own, we quickly realized we had to build up a big reserve – it almost can’t be too big. Because it’s not a matter of if in this business. It’s a matter of when! If you’re operating up here, you’d better be prepared for an ongoing string of expensive fixes. There is always something coming.”

Aside from the lack of help in an emergency situation, Olesen is uneasy about the quiet skies for another reason.

“It’s really interesting now to see the evolution of the industry in remote areas. I don’t see the next generation coming up behind us showing any strong interest in bush flying as a career, and it baffles me.”

That lack of interest can perhaps be attributed to the ongoing pilot shortage. It’s no longer necessary for newly minted pilots to log hours in the North before getting their “big break.” Instead, airlines are competing to hire as many pilots as possible, creating a vacuum that affects smaller operations first.

And, of course, the economy plays a big role.

“In the North there’s not a lot of [aviation] activity right now – with mineral exploration down, everybody is struggling,” observed Olesen. “And that just compounds my sense of, ‘OK, if we do break something out where I work, it will be wildly expensive to get it fixed.’ There are very few piston singles on skis [to fly a part in if needed].”

While the Olesen daughters, aged 20 and 23, have shown some interest in aviation, mom and dad aren’t pushing the issue.

“I think pilots in aviation families have to tread carefully,” he said. “You can’t assume anyone wants to do something. They have to find their own path.”

Steering the course

As Olesen contemplates the future, though, he is mostly pleased.

“We’re really in a situation now where people like us and we can charge what we need to charge, per hour or per mile. And that makes a big difference.”

Kristen holds down the fort as base manager, tracking the planes as Dave flies, answering inquiries, sending out invoices and paying bills. As often as she can, she’s outside feeding her photography business with a never-ending stream of northern subjects.

“I think we’re both of a mind that we’d be quite happy to have an uneventful course to steer for the next few years. There are some aspects of this business that are a pain in the neck. So, when I’m finally out there flying, I have made a resolution to try to enjoy every minute.”

From his unique vantage point, Olesen has watched two wolves take down a caribou from 1,000 feet above. He’s seen caribou migrations, beautiful and strange atmospheric conditions, and the wild and variable weather brought on by climate change.

“One of the lessons of living out where we do is that we know so little. Living somewhere for 33 years – that’s just a blip.”

It may be but a blip, but for the Olesens it’s the story of their family – filled with both good memories and bad.

In the summer of 2014, their homestead was destroyed by a wildfire. The family spent five winters living in their workshop, but finally moved into a new two-storey log home on Jan. 11, 2020 – at 43 degrees below zero.

In July 2017, Olesen’s Bush Hawk capsized in gale-force winds while doing survey work on floats in the Central Barrens. The plane was recovered, undamaged except by its immersion, but one week before it was to return to work, six months after the flip, the hangar facility and office at Fort Nelson burned to the ground, destroying two planes – one of them the Hoarfrost Bush Hawk – and gutting a longtime centre for aviation maintenance in the North.

“When the news of that came in the next morning, you could have knocked me over with a feather,” Olesen recalled.

He said after those major setbacks, he and Kristen are finally beginning to feel that they are “ahead of the curve.”

But there’s never been any illusion that smooth sailing lies ahead.

“Running a little air service in the North is a pretty good gig. It’s not for the faint of heart or for anyone who wants guarantees. It sure keeps your interest up.”