Estimated reading time 20 minutes, 33 seconds.

Shortly after midnight on Thursday, May 30, the phones in the Royal Canadian Air Force Combined Aerospace Operations Centre (CAOC) in 1 Canadian Air Division (1 CAD)/Canadian NORAD Region Headquarters at 17 Wing Winnipeg, Man., started ringing. A massive forest fire over 3,300 hectares in size was bearing down on the Pikangikum First Nation, a community of 3,800 people in northwestern Ontario only accessible by air or water, and the provincial government was starting to fear for their safety.

The request for military assistance wasn’t yet official, but the staff in the CAOC that night immediately began searching for resources. At 424 Rescue and Transport Squadron at 8 Wing Trenton, Ont., technicians began stripping a CC-130H Hercules of its air droppable search and rescue (SAR) kit and configuring the aircraft to transport passengers.

By dawn, the Hercules was lifting off with a flight plan for, but little else. It was still unclear if the gravel airfield could support the weight of a CC-130 or if it had the necessary wingtip clearance from obstacles for a bird that size.

The aircrew was instructed to gather information about the fire and the runway, provide a situational awareness report, and then land in nearby Red Lake for gas. By midday, a hasty operational airworthiness assessment had been completed by 1 CAD staff, and the crew had approval to attempt a landing, albeit after a couple of low passes. They were also cleared to keep the engines running while they loaded passengers.

At the same time, staff in the CAOC began locating and coordinating additional aircraft, re-tasking them from other duties to join the airlift. By Thursday afternoon, a CC-130 J-model from 436 Transport Squadron in Trenton was flying sorties between the Pikangikum airfield and Thunder Bay, Ont.

At 435 Transport and Rescue Squadron in Winnipeg, crews had also begun reconfiguring a SAR H-model Hercules for passenger transport and by early Saturday morning it was airborne for Pikangikum, taking over for the Trenton-based H-model and joining four Trenton-based J-models in the airlift.

That same day, two RCAF captains were on the ground in Pikangikum with backpack radios managing the busy airspace overhead, while one of the J-model Hercs was postured to operate with night vision goggles if evacuations were required through the darkness. In addition, two CH-147F Chinooks from 450 Tactical Helicopter Squadron in Petawawa, Ont., were dispatched to Red Lake on Thursday as “an ace in the hole” if reduced visibility or weather prevented fixed-wing operations.

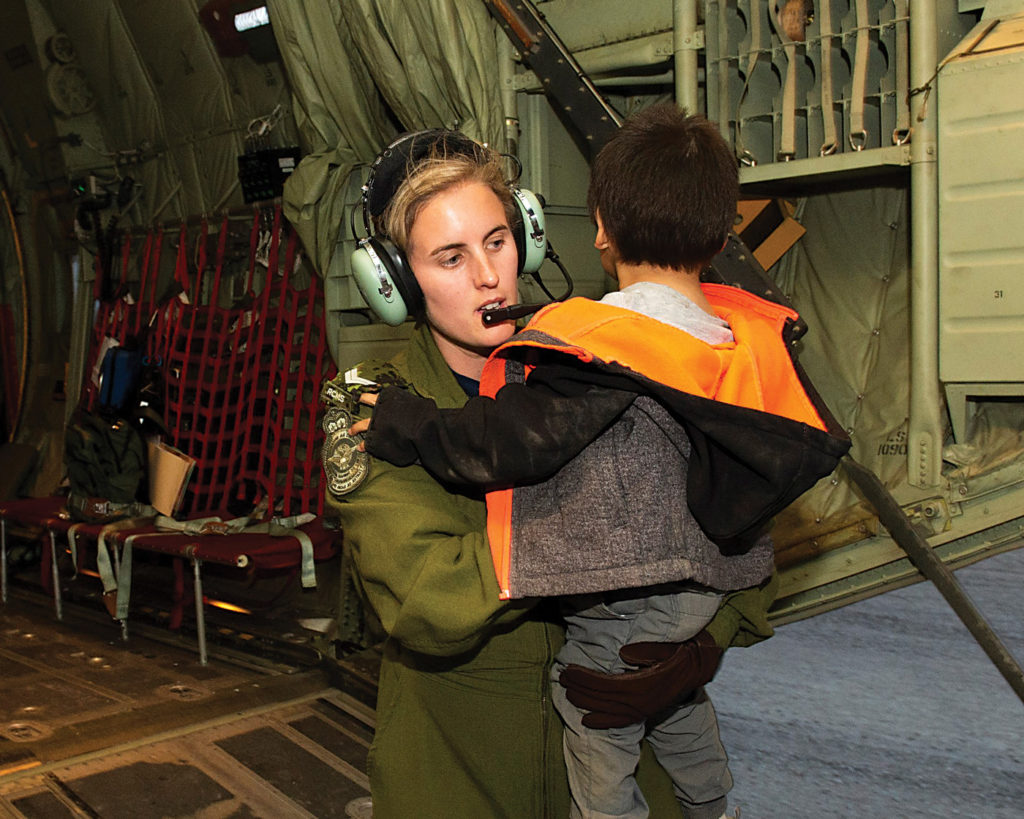

Over a 96-hour period, five Hercules would participate in the airlift, transporting almost 1,800 residents to safety.

Remarkably, conducting the orchestra of Hercules was just the first challenge that weekend. By Friday morning, the CAOC was being advised that the Alberta government was about to ask Ottawa for military assistance as a forest fire threatened its northern communities.

No sooner had the staff begun a divide-and-conquer strategy to obtain the necessary approvals to respond to Ontario while simultaneously deliberately planning for Alberta, a third call from the Canadian Air Defence Sector at 22 Wing North Bay, Ont., put everybody on edge: The Canadian NORAD region (CANR) surveillance operations centre and Nav Canada were tracking an unidentified and noncommunicative aircraft in Quebec showing abnormal altitudes.

Though it did not appear to pose an immediate danger to population centres, CAOC staff began a process to evaluate the possible threat. It eventually turned out to be a small aircraft with a faulty transponder showing it at 60,000 feet, but the call prompted the CAOC to consider an intercept from a CF-188 Hornet on NORAD quick reaction alert (QRA) duty.

“That is our daily existence,” said BGen Christopher Ireland, who was on the floor that weekend. “On any given day, the CAOC is bouncing between the defence of North America and providing air power to take care of Canada’s needs domestically and internationally. And then we’re on call for the other no-fail mission, search and rescue.”

Ireland, a U.S. Air Force officer, is the deputy CANR commander and deputy Joint Force Air Component Commander (JFACC) for Canadian Joint Operations Command (CJOC) in Ottawa. He said the Air Force effort that weekend was illustrative of a structure that is both highly responsive and extremely compressed.

The CAOC is under the direct command of the commanding officer of 1 CAD, who also serves as the JFACC for CJOC, the CANR commander for NORAD, and the commander of the Trenton search and rescue region, which covers approximately 10 million square kilometres of Canadian territory. Those four hats were all in evidence as events unfolded.

When the first call came in, staff were able to immediately harness SAR resources that are on high alert every day. By Thursday afternoon, the response had transitioned to a domestic operation, known as Op Lentus, and responsive to CJOC under the JFACC hat. All the while, the NORAD mission was never out of mind.

“All the same people in the headquarters working the same problem, but doing it with the commander’s different hats on,” observed Ireland. “In a bigger air force like mine, all those things would be divided amongst multiple headquarters…all having to coordinate with each other and with the headquarters that would be the force employer, negotiating which aircraft and when they would start working.”

“At the CAOC, it is all done on the move because it is the same people representing the same boss. In a military scheme where the scale is not enormous, you get a massive amount of efficiency and effectiveness of having that multi-hatted relationship, because you can pivot quickly and not be burdened by your institutions and bureaucracies,” he said.

“You do it safely and professionally, but at great speed, which is phenomenally unique for me from an American perspective. The speed at which the RCAF does business, the agility and the flexibility that it has to go in different directions, has been eye-opening.”

EYES ON ALL AIRCRAFT

The CAOC was stood up in July 2009 as part of a modernization of air force operations and the need for more coordinated command and control over a range of air assets. Its first major operation was under the NORAD banner, monitoring and defending the airspace over the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics. A decade later, it is often described as the nerve centre of the RCAF, with an eye on every aircraft conducting operations in Canada, North America and overseas, and on aircraft supporting training exercises at home and abroad. Part air traffic control, part mission management and logistical support, part obscure problem-solver, it never sleeps.

When Skies visited on an overcast spring morning this year, the CAOC was actively coordinating the movement of six CH-146 Griffon helicopters from bases in Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick as Canadian Armed Forces joint task force commanders in the Atlantic, East and Central regions of the country requested reconnaissance and surveillance of swollen rivers and flooded towns and cities in all three provinces on behalf of civilian agencies.

The six helicopters were just a small part of the aircraft picture on the four massive screens that dominate the secure room. In Mexico, a broken CC-177 Globemaster was still on the tarmac, waiting for a part and mobile repair team. The plane had been participating in an exercise with the Mexican Air Force and had served as the transport for RCAF commander LGen Al Meinzinger, who was now heading home on a CC-130J Hercules.

In addition, two CP-140 Auroras were participating in a United Kingdom anti-submarine warfare exercise called Cable Car and CH-147F Chinook and Griffon helicopters as well as CC-130 Hercules were preparing for Exercise Maple Resolve in Wainwright, Alta., the Canadian Army’s largest annual training and validation exercise.

Over the Caribbean, an Aurora was conducting counter-narcotics and human smuggling operations as part of Op Caribbe from El Salvador; in Mali, Griffons and Chinooks were providing transport and medical evacuation to coalition forces on Op Presence; in Iraq, Griffons were transporting special forces and other military leaders and equipment on Op Impact; in the Mediterranean, a CH-148 Cyclone helicopter aboard HMCS Toronto was supporting Op Reassurance; and various CC-177s and C-130Js were helping sustain operations in Mali, Iraq, Latvia and the Ukraine.

That air traffic didn’t include the two most critical national sovereignty operations, SAR and Noble Eagle. That morning SAR assets from Griffons to CH-149 Cormorants, CC-115 Buffalo and CC-130H Hercules were on 30-minute standby at bases from Greenwood, N.S., to Trenton, Winnipeg and Comox, B.C. On average, SAR crews respond to over 10,000 incidents a year. And in Cold Lake, Alta., and Bagotville, Que., pilots and CF-188s were on alert to be scrambled under the NORAD mission.

Aircraft may belong to the squadrons and Wings from which they operate, but when the CAOC receives a request for an air asset from CJOC, a Regional Joint Task Force commander, an Air Task Force commander or the Army or Navy, that asset becomes CAOC responsibility. Flight plans, diplomatic clearances, dangerous goods requirements–all coordination and paperwork are managed and tracked from the CAOC.

And if an aircraft breaks down on operations? That, too, is often handled from the Centre, which processes almost every request from a theatre of operations on behalf of the RCAF. In fact, when Joint and Air Task Force (ATF) commanders depart for foreign soil, the CAOC telephone number is never out of reach.

“Before they go out the door, we give the ATF commander a brief. They are told, ‘If ever there are any doubts, call the CAOC. We will figure it out’,” said Col David Proteau, an Aurora air combat systems operator and the CAOC director.

He had doubts about preserving his sanity after the first few months in the Centre. Today, though, “it is by far the most rewarding job I have ever had,” he said. “It’s the most dynamic job I have had and the most challenging in my 32 years. But the sense of accomplishment is unlike anything else. We get great people. No matter where or what trade they come from, they all develop this operational mindset.”

Added Col Chris Shapka, deputy CAOC director and mission support division chief: “It’s different every day. You don’t know what you are going to be working on until you come in each morning.”

LARGE SCOPE, LIMITED PERSONNEL

The CAOC includes the Air Operations Centre (AOC), which is staffed at all times by a senior operations duty officer (SODO) on a 12-hour shift, a defensive duty officer, and two defensive duty technicians. An on-duty Chief of Combat Operations, or CCO, is continuously in touch with the CAOC, and a general officer is always either in the building or on call.

As things heat up, computer stations arranged in an inner and outer ring are staffed by experts in combat plans, air mobility, mission support and intelligence, each linked to a cell elsewhere in the building. There are also advisors constantly on-call: a Division Surgeon to advise on health requirements for deployments or coordinate medical evacuations, legal and public affairs officers, a CBRN (chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear) defence specialist, and others.

For an operation like Lentus, a crisis action team often fills the room to handle the varied requests from the military and civilian agencies such as the RCMP and Nav Canada.

By managing the many operational details, the CAOC allows the RCAF’s wings to concentrate on generating aircrews and commanders in theatre to focus on their mission, explained LCol Justin Boileau, an aerospace controller and the CAOC’s regular CCO.

But the Centre is “stretched pretty thin,” he acknowledged. An international study conducted in 2013 concluded the optimal establishment for a CAOC was about 225 personnel. Given the size of the RCAF, a more realistic number would be around 135. The CAOC currently manages with just over 50 staff, said Proteau.

“The scope of the work is no different than what it is in the U.S. Air Force,” said Ireland. “It is a massive scope. In my air force there are thousands of people on different staffs taking on those problems. On the hard, deeper, more complex problems, the lack of scale is challenging.”

Sufficient staffing could be addressed through a CAOC modernization project, which is in the early stages of assessing requirements, facility improvements, connectivity of secure and nonsecure communications with NORAD and CJOC, and investments in technology. It will also deal with continuity of operations if the CAOC is forced to relocate to another building or another base.

The current limit on available personnel is mitigated somewhat by a robust planning process. Deliberate long and short-term planning is handled by a team at 1 CAD, but once those plans are complete, they feed into the Total Air Resource Management plan, a document detailing exercises and operations that will need support over the next 12 to 18 months. That is updated with a biweekly Master Aerospace Action Plan that includes new Requests for Effects (RFE) from operational commanders and sister services and the current SAR posture, which is in turn translated into Air Tasking Orders for the commander of 1 CAD to sign off. The cycle is ratchetted up to every 72 hours during a NORAD mission or a war.

As the old adage goes, no plan survives first contact. “It always gets disrupted,” said Squadron Leader Richard Cooke, a British exchange officer and the combat plans division chief, but the overall plan provides a common starting point on which to pivot when the CAOC is required to adapt on the fly.

Every RFE is entered into a database that feeds the CAOC. Commanders may request a specific fleet to satisfy their airlift request, but the air mobility division determines what is available and the most effective way to move passengers, equipment or supplies.

“We are maxed out, so we don’t want to fly an airplane empty if we can avoid it,” said Maj Dana Sponder, who oversees a team of 12 people to monitor and task all RCAF airlift, whether it is via CC-150 Polaris or CT145 King Air. “We’ll fit in as many jobs as we can.”

One of her challenges is that different countries have very different reporting requirements for aircraft and dangerous goods transiting or entering their airspace. Sponder’s team coordinates diplomatic clearances, but the reporting timelines vary from one hour for some countries to 30 days for others. If an aircraft is delayed or the schedule is changed, it can result in a new request being filed or new routing, clearances and approvals.

“I didn’t realize how many fingers I have in everyone else’s business,” she said.

Operations Presence and Impact are currently her most demanding, but even the deployment of a CP-140 Aurora on an operation or exercise can tax resources; the maritime patrol aircraft require a CC-177 Globemaster just to move their support equipment, a challenge given that the fleet is the most in demand but has limited crews to fly them.

“The big piece is last minute changes,” she said. If a high priority task is activated on short notice and a mission must be canceled, or even if a plane brakes down anywhere, “we are forced to rejig the Tetris puzzle.”

“A lot of different factors determine how to get people and parts into theatre,” acknowledged LCol Chris Shapka. As the mission support division chief, he and a small team problem-solve issues with aircraft maintenance, logistics, telecommunications and construction engineering. A desk officer for each functional area resides in the CAOC, a phone call away from any theatre.

When he spoke to Skies, his team was sourcing parts for the broken CC-177 in Mexico, trying to resolving an IT problem with SAP-based resource planning program in Mali, and ensuring a mobile repair team was on its way to Oman to repair a Cyclone helicopter.

The Cyclone, he admitted, was “the fleet with the greatest discovery at the moment.” Any problem with the new maritime helicopter, which only achieved initial operating capability in June 2018, is often the first experience for maintenance technicians. “Every time something happens, it is the first time it has ever happed,” and the Air Force works with manufacturer Sikorsky and its suppliers to get parts into theatre.

The CAOC even keeps tabs on all aircraft involved in special events, from flyovers of the NBA championship celebrations, the Grey Cup and Canada Day to the Snowbirds and CF-18 Hornet Demonstration teams. Those events might not seem like core missions for the Centre, but they require planning, logistics and support, said LCol Darryl Shyiak, a current Reservist and a former Snowbird lead who serves as the special events division chief.

As with any other RFE, special events are incorporated into the master plan and often supported with a ground team that can include a flypast director to coordinate timing and a safety pilot to provide a second set of eyes for demonstration pilots.

“Everything to support the team is done here,” said Shyiak, noting that if the Demo Hornet breaks down, sourcing spares is an immediate priority.

While each division of the CAOC can take centre stage at times, the stage manager behind the curtain is the senior operations coordinator. Michel Tremblay, a former aerospace controller and the deputy director of the CAOC when it was first stood up 2009, monitors all requests from across the Canadian Armed Forces.

“We have the pulse of the centre,” he said of his team during a brief pause in Op Lentus requests. If an aircraft breaks or is delayed, disrupting the plan, he must be aware of contingencies and which Wing or squadron can “plus up.”

The centralization of expertise in CAOC and the multi-hatted construct of 1 CAD has significantly improved decision making, he observed. “We (the CAOC) are there to facilitate all these different hats. We don’t have that many aircraft and there are a lot of competing taskings.”

MITIGATION AND RISK MANAGEMENT

Balancing competing demands for resources is a constant challenge that is “more art than science,” said Proteau. The no-fail missions of SAR and NORAD might take precedence, but even then, the CAOC has to be conscious of robbing force generation to pay for force employment, and the longer-term consequences when training is compromised.

The master planning process attempts to factor squadron training requirements into aircraft availability, but the Air Force will often push ahead if a job needs to get done, he said. The CH-147F Chinook is probably the best example of a new fleet that deployed to meet an urgent demand. Consequently, some of the maintenance is being learned in Mali, he said, and “deployment has had an impact on [450 Squadron’s] force generation capability.”

Even recurring support missions will face difficult decisions. If a J-model Hercules is providing sustainment to Op Impact, but needed by Special Operations Forces Command in Africa, “do I cancel Impact to support SOFCOM or wait several days because Op Impact is too critical?” asked Proteau, noting the answer is “rarely clearly defined” and often involves accepting some risk.

While that may mean the CAOC drops a ball from time to time, “we will pick up on the first bounce. Rarely do we say no to something critical. We often scratch our heads and find a way we can do both.”

The binational relationship of NORAD mitigates some of that resource management, said Ireland. Canada and the U.S. can share fighter response and air-to-air refueling capabilities if other aircraft and crews are unavailable.

“Those decisions are fully informed by the context of the moment,” he said. If a scenario like Thursday’s unfolds, “we will check with the intelligence division [about potential threats], and then assign resources, after consulting with NORAD and CJOC. I can do that knowing I’m not robbing any one mission to pay the other.”

Thank you for the article, I would like to point out that it should read “in Ukraine” not “the Ukraine”.