Estimated reading time 14 minutes, 47 seconds.

I’ve been married to Robin for 37 years. It would be misleading to say I won her in a Stampe biplane, but it’s true, in a way.

It was 1980. Robin had begun flying training and had met a group at Maple Airport (in Vaughan, Ont.) who intrigued her with loops and rolls in a Decathlon and a Pitts. She became an accredited judge at aerobatic contests.

I was a young DC-9 first officer borrowing my Dad’s Stampe-Vertongen SV-4B and learning the Sportsman sequence.

Our paths crossed at the Canadian Open at Centralia, Ont. I noticed she arrived in a Pitts S2. She noticed I was there with the Stampe. Each of us thought the other owned the airplane! We were both wrong, but we didn’t let that stand in the way.

Two months later, we were buying a house together and a year later, we were married. And we have been flying together ever since.

But the Stampe named “Mam’selle” was key.

Dad (Roger Hadfield) bought the elegant biplane in 1977, when he was 43. Almost no one in our neck of the woods had ever heard of one before. But aerobatics fascinated him. At the time he was inverting the family Citabria, but itching to do more.

Stampe #16 served as a basic trainer with the Belgian Air Force from 1948 to 1968. A few years later, it was purchased by RCAF personnel serving nearby, and along with four other machines was brought to Canada in the belly of an empty CC-130. (The good old Air Force!)

De Havilland guru Watt Martin peeled the fabric, repaired as necessary, recovered it, and overhauled the late-model Gipsy 10 engine. After only a year or two the owner, Glen Beiderman, decided to move on, and Dad bought the aeroplane, registration C-GOMD.

Like a Tiger Moth, only better

Jean Stampe was a First World War aviator and King Albert of Belgium’s personal pilot. In peacetime, he formed a company with financier/pilot Maurice Vertongen and designer/builder Alfred Renard, and started a flying school. In 1927, they became the Belgian dealer of De Havilland products. But by the 1930s, he decided to build a better trainer. The story is he wanted to create a biplane with none of the faults of a Tiger Moth–he wanted to take its strengths and improve upon them.

Renard had left to form his own company by then, and Georges Ivanow was hired to design the new aircraft. It was called the SV-4. Only about 35 were built before the Germans invaded, but after the war the Belgian Air Force contracted for 65 more, with the latest DH Gipsy 10 engine. They served as basic trainers until the late ’60s. The French Air Force also liked the design and 840 of them were built by Farman as the SV-4C, powered by the Renault 4 Pei.

When you first see a Stampe, you tend to ask, “Which model Moth is that?” There is certainly a general resemblance. But it’s subtly different in every line. There are four ailerons, not two. The wing sweep and dihedral have changed. A different airfoil was used. The fin is larger and so is the rudder. All the tail feathers have significant airfoil sections. Control gearing is utterly different–the strange De Havilland aileron rotary gearing was scrapped. The aircraft is shorter in wingspan and length.

The result is a far more nimble beast. It delights. There is a wonderful quality of grace in the way it flies, a feeling that comes to you through the stick. Its roll rate doesn’t match modern fire-and-brimstone airplanes, but it goes up on a wingtip on a mere whim. All you need to do is guide it around. Control forces are fingertip-light. It’s impossible to fly one straight and level. You merely think about manoeuvring, and you’re there.

The late ’70s and early ’80s saw Dad in the sky west of Milton, Ont., on most of the flyable days that he wasn’t piloting a DC-8. In his first year, he won in the Sportsman category. In 1978, he won Intermediate, beating seven Pitts aircraft for the trophy. (He’d learned to “fly for the judges.”) In 1980, we each won in our categories.

A Stampe has nothing like the vertical performance of a Pitts. Each foot of altitude must be laboriously gained and preciously husbanded. Any crude mistake costs. To match one up against a modern aerobatic aircraft–and win–requires you to finesse every manoeuvre. Each pull to the vertical must be just right; too hard and the drag kills your speed, too gentle and you don’t have time to draw an upward line. You nurse it around the tops of Cubans–it seems to keep flying with zero airspeed. It can be “floated” through some manoeuvres. The roll rate is good for a ’30s biplane, but it doesn’t compare to a Pitts. For Dad to gain competition victories in the Stampe was a testament to skill and smoothness and endless practice.

He was also ruthless about weight, yanking out the starter, generator, front cockpit instruments, battery–everything he didn’t absolutely need. We boys learned to hand-bomb a prop–safely!–as soon as we were tall enough to reach it.

She’s a quirky one

The Stampe does have some quirks: The brakes are like the early De Havilland aeroplanes, applied with a hand-bar on the left side of the fuselage. Pull that and both wheels will be braked evenly if the rudder is centred and the cables are set up correctly. (Two big “ifs!”)

If you pull it when the rudder is displaced, you get braking on that side. In real-life, especially in a crosswind landing, that system only works if you have three hands (throttle, stick, and brake). Dad learned quite early to rig the brakes so that if you went hard-over with the rudder, right-to-the-stop, you got almost enough braking to stop a wheel. (And that’s without pulling the brake lever at all.) This allows instant correction. No fumbling. It has kept the aircraft intact during many troublesome crosswinds.

Another weirdness is the “inverted” fuel system. It’s controlled by four levers on the quadrant on the cockpit left side. The top lever is just the butterfly-valve of the throttle, like most carburetors. The lever underneath it [black] controls a needle-valve which squirts raw fuel under pressure into the manifold intake. This is the pressure “inverted” system. When in use you handle the two levers at the same time in the palm of your left hand. If you want a richer mixture, you lead with the heel of your hand pushing the lower lever forward. If the engine is making black smoke–running too rich–you lead with the upper lever; the ball of your hand. (This is a similar concept to some First World War rotary engines.)

And all that would be fine except that this pressure system is too crude to allow the engine to idle. For idle-power manoeuvres, such as spins, you must be on the normal system! Which means you have to consider how long it takes for the carburetor bowl to fill, or empty (because you can’t run on both) during your display. An example: If you want to loop after a spin, you must start out on the normal system. But well before entering the spin, you must push the bottom lever [orange] forward, which shuts off fuel to the carb bowl. If you time it right, the bowl empties as the aircraft recovers from the spin. The engine quits but instantly you bring the pressure-system lever forward and the engine immediately catches again. Quite something to remember during a sequence!

The other lever, third from the top [blue], is the mixture control for normal flying, but in inimitable De Havilland fashion it works not by reducing fuel, but by adding air to the fuel-air mix. It’s moved back for rich.

For another 30 years, the Stampe was part of the family. All five of us siblings knew it intimately –through wiping oil off the belly, and lovely cavorting flights off the farm or cottage strips. My son, Austin (now an Airbus A320 captain with Air Canada) spent a month in it with his grandfather during summer break from Sault College. They tried to visit every grass strip in southwestern Ontario. Austin soloed it — a rare honour.

Sparkling and renewed

By 2015, C-GOMD was getting tired. It was clearly time for rejuvenation. I put Dad in touch with Stan and Sheila Vander Ploeg of Grand Valley Aircraft Restorations, northwest of Orangeville, Ont. I’d seen them repair and recover the Edenvale Classic Aircraft Foundation Tiger Moth in just one winter. They are wood-and-fabric specialists, a great team, and I was impressed.

After a few meetings, a deal was struck. OMD was disassembled in the hangar at the farm and trucked to their place.

It’s vital to have a clear understanding between all parties before starting a project like this. Both Stan and I made it very clear to Dad that the work would cost much more than the resale value of the aircraft. And, it would occupy two winters.

His solution was to say, “Get started,” and then he bought a C-170B to fly while he waited.

This turned out to be a great move. It had been a long time since Dad had owned a cabin airplane. With only him and Mom on board, the 170 made easy work of the 1,600-foot farm strip. They ranged all over southwestern Ontario, chasing the perfect lunch. Fly-ins, airshows and pancake breakfasts lured them out.

We had a hangar built at the strip near the cottage (Corunna, Ont.), and parked the aircraft indoors, along with my Fairchild 24W or Robin’s RV6A. Chris woke up his taildragger feet in response to Dad’s thorough checkout, and soloed it. (Which in September 2018 led to flying Mike Potter’s new Spitfire.) So did brother Phil, a 787 captain.

In the meantime, the Stampe progressed. Stan looked a little blank when I presented him with full drawings and notes written in Belgian technical French, but persevered. There were endlessly time-consuming repairs to the 75-year-old wood of the wing ribs and trailing edges. Sheila became an expert at drawing 25W60 engine oil out of the fuselage wood.

I sourced parts all over the world and Stan put his contact list to good use for items that needed specialist repair. But there were no surprises, just labour, and she came together steadily.

The ceconite fabric went on beautifully. (“A couple that stitch together, are fixed together!”)

The doping was interminable, particularly when the coloured coats began to go on. Dad wanted exactly the same paint job, which meant miles of masking tape. Stan and Sheila worked together, hands-on, and it showed.

The wings went on and the engine first fired up in June 2018, right on schedule. The brilliant new paint and the sweetly-barking Gipsy 10 were a feast for family and friends. For us, it was like stepping back in time.

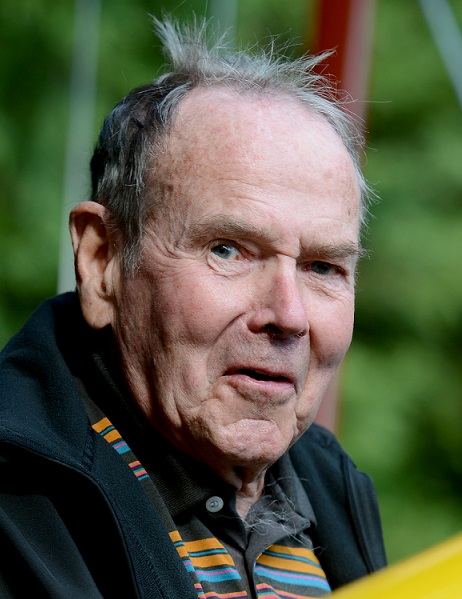

Dad is well into his ’80s, but no one knows a Stampe better, and he did all the test flights. “Dave,” he later said to me, “it flies better than it ever did. They got the rigging right–first try!”

Soon the Stampe was at the cottage airstrip, and the summer of 2018 saw the aeroplane gamboling over the fields south of Sarnia like it always had!

Recently, at a gathering south of Tillsonburg, Ont., we linked up with Eric and Bernadette Dumigan for an air-to-air photo session. Eric had captured the Stampe 20 years ago during a similar flight from Geneseo, N.Y., and it was sweet to do it again with the aircraft fresh and new. Chris flew the 170 as the camera plane, and Bernie and I flew chase in the RV6A.

We landed and felt a wonderful sense of turning back time. We shook hands, laughed, took photos, and delighted in the moment.

To share in the return of the Stampe, still in the hands of her owner after 42 years, sparkling and renewed, was a life memory to treasure.

Dave Hadfield is a 27,000-hour retired airline pilot who recently flew Mike Potter’s Spitfire IX on a 5,000-mile trip from Gatineau, Que., to Comox, B.C., and back. A singer-songwriter, his most recent album, “Climbin’ Away,” was released at Oshkosh last summer. He lives near Barrie, Ont., flies his Fairchild 24W, and his wife Robin is a director of the 99s, and flies her RV6A. www.hadfield.ca

Sidebar by Roger Hadfield

The Stampe: A joy to fly

The Stampe is a luv!

The aircraft’s appearance is similar to a Tiger Moth in that it is a swept wing biplane with a Gipsy Major inverted engine. But there the similarity ends!

It has a shorter span, shorter chord, four ailerons, and an inverted fuel system, but most important is its flying tail. Both tail surfaces are airfoil both ways, which allow the pilot to make something out of nothing in aerobatic displays. The airflow from the prop flows undisturbed back along the flat sides of the fuselage and keeps the tail effective well below minimum speeds.

With the meagre 142 horsepower (on a good day) you can’t power your way through or out of any figure. It is essential to make use of every bit of kinetic energy available as you enter and ride through a manoeuvre.

For instance, the Stampe will not fly knife edge. However, I’ve done many knife edge passes low and close to finish a sequence and quarter roll to push out in an inverted turn. The apparent knife edge flight is accomplished by humping the nose up as you quarter roll to knife edge attitude, allowing the aircraft to ride a parabolic arc on the kinetic energy of the quick pull up.

To fly a snap roll without undue G and strain it is essential to accelerate from about 60 knots to 80 and enter the snap riding on the energy created by the acceleration.

I was blessed, 42 years ago, with Neil William’s book Aerobatics as my bible for aerobatic training. He wrote the book around the Stampe and his description of figures were precisely tailored for the Stampe.

I would read the instructions, then go up and try the figure and then, usually, come back down to read it again to see what I did wrong. The second flight was often much better.

All rolling and looping manoeuvres can be flown right in front of the crowd, and the lovely round figures flown at low speeds with a good margin of safety are most pleasing to the eye.

All fine flying aircraft tend to become an extension of the pilot and the aeros are flown often without conscious inputs. With the Stampe this is especially so and makes the aircraft a joy to fly!

It is a wonderful experience for me, in my 85th year, to fly “Mam’selle” again, fresh from recover-and-repair and flying like a dream.

Thanks to Grand Valley Aircraft the rigging was perfect, first time, and the Stampe seemed eager to display her fine manners.

Then, with my son Chris flying the photo C-170, Eric Dumigan captured the beauty of a Stampe in flight.

Great story, bit similar to mine and I also flew Spitfire.

If ever you come past Belgium (Trump said it’s a nice city) do not forget to visit the Stampe Museum in Antwerp.

I enjoyed reading your story, the title could be “Born to Fly”.

My Father built airplanes at de Havilland. I have a photo of him in front of the 1000th Mosquito when it was completed.

Great article Dave and Roger, also loved seeing all the older pictures of the family with the plane.

We imagine we’ll be seeing a lot of the Stampe this coming summer.

Howard hopes to see the Spitfire maybe this summer.

Thanks Howard & Maureen

This is the ex-Belgian Air force SV-4b V-16.

Nice to see hime in this article.

Greatings from EBTN / Goetsenhoven Belgium

Jozef Vandevorst

Sounds like a true Love Story. True passion. Looking forward to seeing it.

I flew in this airplane with Glenn Biedermann. We took Hwy 25 to the Queen E, and on to Niagara Falls and back. It was an experience I never forgot. It is great to see this story.

Wow, what a great article! Thanks for the stories.

Incidentally, my dad Ron Uloth, was one of the guys who originally imported your V16 (along with his V22) into Canada back in 1971. Time sure flies.

I was thrillled to find this story. For quite a few years I attended the air shows at Geneseeo, and enjoyed seeing your Stampe on the ground and in the air. It was a treat to be able to chat with Roger a pout the plane and his experiences. It was great to read that the plane still is in the air.

I fly a quarter scale RC model of the Stampe, which flies much like your full scale. I get many comments on how graceful and smooth it looks in the air. That’s just a testimont to what I learned from the chats and watching the shows. Thanks!