Estimated reading time 21 minutes, 52 seconds.

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

July 2, 1937, left a memorable imprint on the history of aviation. The Lockheed Model 10E Electra plane piloted by Amelia Earhart on her around-the-world flight vanished without a trace in the southern Pacific Ocean, over 20 hours after takeoff at Lae, Papua New Guinea, where she and her navigator, Fred Noonan, were last seen alive. Sadly, the closing stage of her longest journey was not completed.

Investigating the Earhart case is Richard Gillespie of The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR). Unlike those who preconceive the plot and then seek evidence to support it, Gillespie formulates the possible scenario armed with hard evidence — in the case of the Earhart investigation, this includes an aluminum sheet with rivet holes, a freckle cream jar, and the signals received by radio stations located in the North Pacific Ocean.

Writer Thomas Ughan spoke with Gillespie on July 3, 2020 — a day after the 83rd anniversary of the Earhart disappearance — to gain insight into the search for artifacts potentially related to Earhart’s final destination.

Thomas Ughan: Let’s start with the existing theories on how Earhart disappeared and what eventually happened to her. Here we have a landscape of conflicting propositions: the crash-at-sea theory, the survival theory, the spy hypothesis, and the Japanese capture scenario with the Jaluit Harbor photo. There’s also a suspicion that the U.S. government knew of Earhart and Noonan remaining in Japanese custody. And finally, your proposition that advocates the importance of the artifacts from Nikumaroro Island and other, less tangible evidence. Is it Earhart and Noonan in the Jaluit photo? The year 1937 proved wrong when it was revealed the picture was dated 1935.

Richard Gillespie: In 1935, Amelia Earhart was in Hawaii and her movements are very well documented. This gets to the essence of all historical investigation: You cannot go into it with an agenda. You cannot decide what happened and then look for evidence that it happened because you will be selective. You’ve got to base it on facts and then go wherever the facts lead you — without emotion. Of course, we all have emotions, and once you look at the facts — having invested time and effort in your theory — you surely want to be right. So, you have to be constantly on your guard against what’s known as confirmation bias.

Ughan: What experts participate in the Nikumaroro investigation?

Gillespie: Archaeologists, navigation experts, anthropologists, and forensic imaging specialists. What we do is change mystery to history through science. We are an educational organization and that’s our purpose: education. We use these famous mysteries to explore, demonstrate, and teach the scientific method of inquiry — how you go about figuring out what is true. And that’s what it’s all about for us.

Ughan: What’s wrong with the theory that the U.S. government knew Amelia Earhart remained in Japanese custody, but didn’t reveal this to conceal their techniques of espionage and maintain military advantage over Japan?

Gillespie: First of all, as far as anyone knows, there are no U.S. government documents related to Amelia Earhart that are still classified. People have filed for freedom of information requests and nobody has ever been denied access to the files. Everything has been declassified. And there’s nothing there to indicate Japanese involvement in her disappearance or that the U.S. knew anything about it. That’s how conspiracy theories work. I’ll believe it if you show me the evidence, and there isn’t any!

Ughan: Let’s talk about the artifacts that you found on Nikumaroro Island, formerly known as Gardner Island, which you consider with a high degree of probability to be her deathplace. Could the freckle cream and the other items have belonged to another woman? Do you never doubt your interpretation of what happened there, or could have happened in July 1937?

Gillespie: The island’s history is scrupulously documented because it was a British colony and records were kept. I can tell you the name of everyone who ever lived there among the total of almost 200 people. I have the British records of who they were and where they lived, and we know what happened where the artifacts were found. We can’t find a record of an American woman ever being on the island, other than possibly Amelia Earhart. So this freckle cream jar is interesting because it’s an American product for women from the 1930s, and there were only Pacific islander women on the island. They don’t have freckles. So, we can’t find a better explanation. We know the bones of a castaway were found at the same location where this freckle cream jar was found. And other evidence leads us to fairly believe it was a woman and almost certainly Amelia Earhart, so the jar gives the best explanation.

Ughan: Who did the freckle cream belong to if not an American woman with a freckle-prone complexion?

Gillespie: Right. But unless you have an artifact that can be specifically linked to Earhart in some way — for example, a wristwatch with an engraving on the back of it…

Ughan: That’d be rewarding.

Gillespie: Sure. We may have something like that, we’re still analyzing that, but nothing we found at the site where the castaway’s bones were found gives us this certainty. So, yes, there could have been another woman who used freckle cream. It seems like a very low possibility, but it’s possible and you have to accept that. You hope for that one thing that removes all doubt, but rarely do you get it in this kind of investigation. Usually, what you get is a preponderance of evidence. A number of different things that all add up and are explained by the same event.

Ughan: Is there another convincing piece in your collection?

Gillespie: We may have a part of the airplane that we’re still examining — this sheet of aluminum we found washed up on a beach after a storm in 1991. It’s the right kind of metal for her airplane. Based on the rivet hole pattern, it looks like a patch was put on her Electra after the right-hand side window of the airplane probably cracked in Miami; they replaced it with a patch without enough care. Now we’re analyzing the best image we have of the patch on her airplane to be able to match the rivet pattern on the aluminum sheet exactly. This way you identify artifacts. Compare the unknown to the known and if they’re alike, that’s what they are!

Ughan: How much fuel did they carry from Lae? Knowing the fuel consumption of Amelia’s Electra model, direction, and so on, can we specify the distance and locate the crash-landing, or landing spot?

Gillespie: Yes, of course. And that’s much of what we’ve done. We’ve spent years uncovering evidence and getting the hard-copy documentation to evaluate those questions. Mind that airplanes always obey the laws of physics. They can do certain things, but can’t do other things. Then you can define those limits. Lockheed modified their Electra Model 10E for Amelia to increase its fuel capacity. Lockheed Report 487 of 1936 included all the specifics of the 10E with all the things you should do to fly that far. All the engineering was done. We also know that before her world flight, Lockheed’s senior engineer, Clarence Johnson, flew with Earhart in her airplane and worked out a profile of power and fuel management for her to get maximum economy. We know from written sources the total fuel she carried on her departure from New Guinea was 1,100 gallons (4,165 litres). She didn’t carry full tanks, being 50 gallons (190 litres) short of full fuel load. We know the airplane’s capabilities, and we have to assume she followed the recommendations of power management. Then, 1,100 gallons was enough for about 24 hours — enough to reach Gardner Island. This way we evaluate a hypothesis that she ended up on this island. Those who believe she hit the ocean, ‘want her’ to hit the ocean about four hours before she ran out of gas. So they have to prove that she ignored the fuel recommendations, or there was another cause of fuel shortage. But there’s no proof that it happened.

Ughan: So she didn’t crash, but landed intact?

Gillespie: She didn’t crash! We know exactly where she landed safely, and I will tell you how we know that. First, with her radio she could transmit on only two frequencies reserved by law for a U.S.-registered aircraft calling a ground station. So, any radio transmission on those frequencies in the central Pacific area where she disappeared was either from a U.S.-registered aircraft or from Earhart — or it was an illegal hoax from somebody who had the capability. We know that she was last heard from in flight at just before 10 a.m. local time by Itasca, a U.S. Coast Guard ship. We also know that she had fuel for a maximum of 24 hours, so by noon on that day, if still in the air, she was without fuel hoping to find Howland Island. At about 6:30 p.m. that evening, Itasca started receiving radio distress calls on her frequency, and HMS Achilles, also down in the central Pacific area, heard her, too. The New Zealand Star freighter also did. And for the next five nights these calls were heard throughout the central Pacific on those frequencies. Lockheed, the airplane manufacturer, said at the time, “If you’re hearing radio calls from this airplane, the radio isn’t submerged and is working.” The radio direction-finding stations on Hawaii, Midway Island and Wake Island also heard them. And they took bearings on these calls that crossed near Gardner Island. That means the airplane has to be on land, and if she’s transmitting this long — five nights in a row — calling for help, she’s able to recharge the batteries so she can run the engine to generate power for the radio. She’s landed safely, and the calls are coming from near Gardner starting just a few hours after she disappeared. A reliably documented radio transmission, on the particular frequency at the particular time, is like an artifact. A hoaxer would have to know ahead of time Earhart was not going to find Howland Island, which is ridiculous.

Ughan: We know she had 1,100 gallons of fuel taking off from Lae, which was enough to get to Howland. Why then did she end up on Gardner? Did she lose her way?

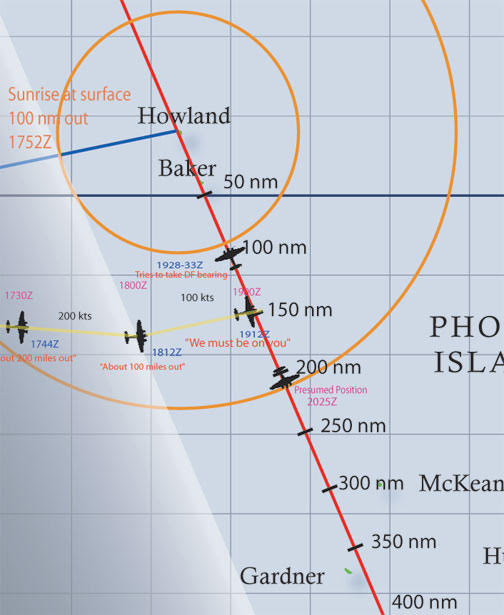

Gillespie: The flight to Howland was expected to take 18 hours. Eleven hundred gallons of fuel gave her 24 hours of endurance, 18 hours plus a six-hour reserve. Early in the flight, she had to make a diversion around some bad weather which cost her one hour, so it took her 19 hours to reach the vicinity of Howland. But, during the night, stronger than expected winds from the northeast drove her south off course, so when she thought she was near Howland (“We must be on you but cannot see you…”) she was actually about 150 miles south of Howland. She knew she was somewhere on a line (157°-337°) that passed through Howland, but she didn’t know whether the island was to her left (337°) or to her right (157°). She searched up and down the line, first to the left and then to the right, looking for Howland (“We are on the line 157-337, running on line north and south”). She didn’t go far enough north to see Howland. Searching for Howland to the south brought her to Gardner.”

Ughan: What events developed after landing, and where exactly did she land?

Gillespie: The U.S. Navy sent a battleship, USS Colorado, from Hawaii down toward Gardner Island. By the time Colorado arrived a week later, the radio signals had stopped. We know why. The airplane had landed on a reef that surrounds the island, which is a broad, flat, smooth area, like a runway. You can ride a bicycle there. But the tide came in, and after five days the airplane was washed off the edge of the reef into the ocean and it sank. It’s a violent place. I’ve been on that reef at low tide. I wouldn’t go anywhere near it at high tide. The Navy didn’t find the airplane. The conclusion was she must have crashed at sea and drowned.

Ughan: What happened next?

Gillespie: Three months later, the British landed on Gardner Island to evaluate the location for future colonial settlement. They weren’t looking for Earhart, but inspecting the place and taking pictures. And one picture shows the western side of the island and the shipwreck of a freighter that hit the reef in 1929. And there’s something sticking up out of the water on the reef, way too far away from the shipwreck to be related to it. We went to the University of Oxford, England, and took off a high-resolution photograph of this picture. Then, our forensic imaging specialist Jeff Glickman did a lot of forensic work to bring out the details; he found it looked like the wreckage of a landing gear assembly from the Lockheed Electra with the tire, the struts, and the other features. I said, “You mean that’s a picture of an Electra landing gear on this reef? I need a second opinion. I need a photo specialist from the Geospatial Imagery Agency to examine this.” And they agreed to do that. When they called me later, they said, “This looks like the wreckage of a Lockheed Electra landing gear.”

Ughan: Did the British find any artifacts there?

Gillespie: Three years after Earhart disappeared, the British arrived to establish a colony there. They sent workers into the island, who discovered a skull. In September 1940, the first colonial administrator Gerald Gallagher arrived and heard about the skull, so he decided to check it. He began a search and found more bones — a partial skeleton. He also found parts of shoes, dead birds, and a dead turtle. He said, “This is a castaway who died here, apparently a woman!” And he thought this might be Amelia Earhart.

Ughan: Did they try to identify the castaway?

Gillespie: They decided to conduct an investigation to check if it was Earhart. The bones were sent to Fiji in December 1940 by order of Gallagher’s superior High Commissioner Harry Luke — although various members of the High Commission insisted on anthropological testing in Australia.

In 1998, after 10 years of searching, we tracked down the original British file in England containing the bone measurements — which were taken in 1941 by a local doctor working in Fiji at the time, to whom the bones were delivered. With no particular training in forensic anthropology, the doctor reported that the bones were of a short stocky European male, not Amelia. The case was closed and the whole thing existed only as a rumor, until 1998 when we found the original file.

Ughan: Another analysis?

Gillespie: We conveyed those results to forensic anthropologists who identify ethnicity and gender. They plugged it into their computer databases available now, and what they got was: “White female of northern European descent, about five feet, seven to eight inches tall.” It’s consistent with Earhart who measured five foot seven. Then we took it further to world-renowned anthropologist Richard Jantz of the University of Tennessee. He noticed that the upper arm bone was short compared to the lower. He said, “I wonder what Amelia was like.” We went to check on one historical photograph where she’s standing in the same plane as something that still exists to measure that thing. The propeller of the airplane she flew across the Atlantic was exhibited in Washington’s National Air and Space Museum. We were able to go there and recreate the photograph, and we got an exact match! So, what Dr. Jantz found and published in the February 2018 edition of Forensic Anthropology was that there is a 99.28 per cent chance that the bones from Nikumaroro are Amelia Earhart’s.

Ughan: This feels hot…

Gillespie: Yeah. So, she got quite far from the airplane exploring the island, but there’s something more. Where those bones were found is really the best place for a castaway to hang out. The island is narrower there, with easy access to the ocean and the lagoon for food. There’s a slight rise in the land there, so you can catch the prevailing easterly winds. And at that time, much of the island was forested with the type of tree that was easy to climb. If you’re a castaway waiting for rescue, you’ll need a place from where you can watch the horizon. So, it’s the right place. Makes a lot of sense. That’s where we found the freckle cream jar and so on.

Ughan: Do we have any evidence strictly related to what happened to Fred Noonan?

Gillespie: We’ve found no sign of Noonan on the island. The man’s shoe found with Earhart’s bones may be one of his she was using. Gardner is very hard on shoes and they are essential for walking on the coral. Several of the radio distress calls describe Noonan as being severely injured. If Noonan died in the airplane, Earhart would not be able to remove the body.

Ughan: Has anyone else invented a theory?

Gillespie: David Billings from Australia is quite convinced that some plane wreckage was reportedly seen in the jungle of New Britain. He thinks Amelia never really got close to Howland Island. The Nikumaroro theory, in our opinion, is the only viable explanation of the established facts. It is the demonstrated answer to the mystery. Everybody says the mystery won’t be solved until the airplane is found. Well, we may have a piece of the airplane, but what appears to be the case is the airplane was destroyed fairly early on — it’s scattered and there’s nothing much to find.

Last year, Bob Ballard, the Titanic finder, was out there looking for the airplane in vain. Everybody wants the airplane out there — and, God, I’d love to have it — but again, we have to look at the facts and accept the reality of what we have. I don’t know if we will ever reach widespread consensus that we have the answer because people want a simple answer like, “Here’s the airplane, folks!”

Well Mr. Ughan. I have like many been intrigued by the story my entire life ( 77 years old) Always much interested in historical fact solving and a need to know obsession . I hold a private pilot’s license in Canada, though not active. I guess this adds to my interest. Your presentation with Gillespie is the best I have read on this. So much has been speculation and inaccurate statements. Thanks for your efforts .I feel more enlightened on the subject than I ever have been to date. Cheers.

July 10 2021

Hello Mr. Little,

I haven’t been on this site for quite long – I’m sorry to reply so late. Thank you very much for your appreciation. This means a lot to me. This is mainly due to Ric Gillespie as he was so kind to share his passion with me. I was just an interviewer sniffing around and trying to find what personally interested me.

Yours sincerely,

Thomas Ughan

Hello Mr. Ughan, what should I do if I have information about the Amelia Earhart’s plane?

First, prior to 1936 Howland island was located 5 miles in the wrong location and I can explain how.

Second, 157-337 has nothing to do with the sun during the summer solstice because June 21 1937 the sun was 23 degrees (67 degrees true) north of the equator. On July 2 1937 the sun would have been 20 degrees ( 70 degrees true) north of the equator.

Amelia was given the wrong true heading and I can prove it. 2556 miles is equal to 2221 nautical miles. If you use 2556 when calculating the true heading you get 78.3 degrees (68.5 degrees compass). BUT if you use 2221 you get 76.5 degrees true heading WHICH IS 67 DEGREES COMPASS HEADING.

They flew 2556 miles on a 76.5 degree true heading then turned right 90 degrees on to 157-337 towards Howland island then turned north where they ran out of fuel. Approximately 50 plus miles north of Howland island and east of true north.

July 10 2021

Hello Mr. Wright,

I am not a navigation expert. I know which way to head north, southwest, etc. however, when it comes to the complexity of flight navigation I can only stand with my brain empty and rely on experts. I think the best idea for you to discuss these issues is to contact Mr. Gillespie of TIGHAR (the organization’s contact email is available on their website) who is probably one of the most renowned specialists in the field of ‘Earhartology’.

Yours sincerely,

Thomas Ughan

This is just an update, I was unsuccessful with trying to confirm the position of the sun on July 2nd 1937. However the position of the sun on July 2nd does not effect my research on whether or not Amelia Earhart and Fred Noonan may have been given the wrong true heading and where flying on a 67 degree compass heading. I believe I have proved that it is possible they might have been flying on a compass heading of 67 degrees. I am now wondering if it’s possible that a 157-337 compass heading can be represented by both 67 degree true heading and a 67 degree compass heading in the same situation?