Estimated reading time 8 minutes, 19 seconds.

Editor’s note: Lola Reid Allin is a writer, photographer, adventurer and commercial pilot based in Belleville, Ont. This is part 3 of a 5-part series by Lola about the under-representation of women in commercial aviation. Click to read part 1 and part 2.

In the 1970s, Canada supported the International Civil Aviation Organization’s (ICAO) decree that pregnancy was a disease, a ruling which automatically downgraded a female pilot’s medical category from Category I, required by commercial pilots, to Category 3.

Lorna deBlicquy, now a Canadian aviation legend, was one of the first Canadian women to make a career in aviation. Her persistent lobbying against the ICAO ruling that pregnancy is a disease helped change government policy. Longing for an exotic career like her brother, a bomber pilot in Second World War Burma, deBlicquy saved her babysitting nickels to pay for flight lessons and soloed in a Piper J-3 Cub on May 11, 1947 — at age 15.

In 1974, she became a Designated Flight Test Examiner, an examiner-in-the-field tested and approved by Transport Canada Flight Training Standards. In 1975, she applied for a job as an inspector with Transport Canada Flight Training Standards and to a commuter subsidiary of Air Canada, as a pilot. She had sterling qualifications, an Airline Transport License, and 6,000 total flight hours accumulated in Canada’s Arctic and subarctic as well as a stint in New Zealand.

When men less qualified than deBlicquy were hired, she publicized this injustice in articles and on radio shows.

Despite her efforts, she wasn’t hired.

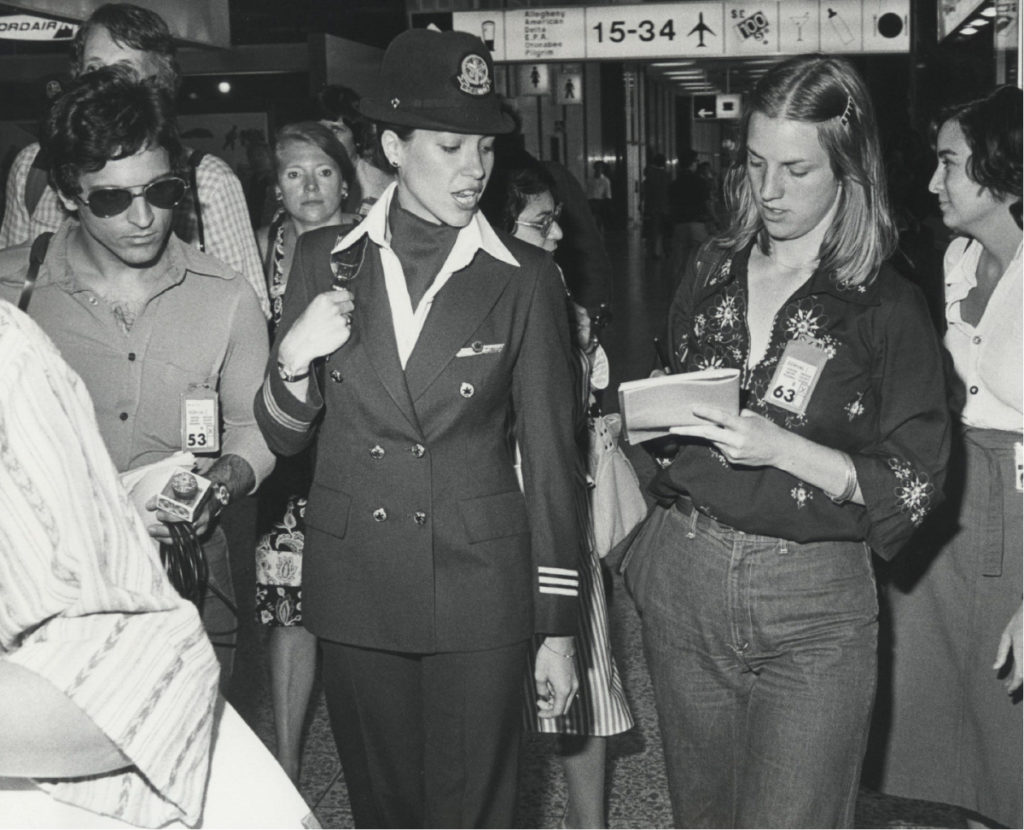

Judy Cameron was the first female graduate of the Aviation Technology Program at Selkirk College, B.C., and the lone female in a class of 30 men. She described her experience as “isolating and difficult.” After graduation, Cameron applied to Air Canada, whose senior officials were interested but directed medical staff to consult studies of female pilots by NASA and American airline companies. When senior officials learned these studies indicated gender irrelevant to emotional stability or the ability to reason logically using a disciplined approach, they hired Cameron in 1978 as a second officer — a non-flying position as navigator.

As the first female pilot with Air Canada, Cameron was a celebrity. One female television reporter enquired, “How do you manage to fly despite the ravages of pre-menstrual tension?”

The challenges that faced women in aviation were not unique to Canada.

Aviation was the only career Britain’s Yvonne Pope Sintes wanted. Because Britain barred women from being commercial airline pilots in the 1950s, she became a flight attendant and, like many other women, used her earnings for flight training. When Sintes earned her commercial pilot wings, she applied to the Royal Air Force, ignoring their published refusal to consider females. Following a tortuous route, she became a flight instructor, and then an air traffic controller — one of two female controllers in Britain. Her determination did not pay off until two decades later when she started earning her living as a pilot, but felt her male colleagues “didn’t like me at all.”

In America, 17-year-old Emily Howell Warner decided on aviation as a career during her first airplane ride. She became a commercial pilot, and then a flight instructor. She first applied to Frontier Airlines in 1968 and frequently resubmitted her application. Sliding beyond age 30, she lost all hope of flying for a major air carrier, especially since some of her former students — all males — had been hired by Frontier. In 1973, five years after her first application, someone gambled to hire her as their first female pilot. Warner began her career as first officer on a Frontier Convair 580, then the de Havilland DHC-6/100 Twin Otter. In 1976, at age 36, she became the first female American airline captain, flying the Twin Otter.

In 1984 in the land down-under, another aviatrix fought her own battle, recounted in the book Letting Fly: Deborah Wardley, Australia’s Trail-blazing Pilot. In 1971, 18-year-old Wardley earned her private pilot wings. By 1976, she was a well-qualified commercial pilot and instructor with 2,600 hours. Between 1976 and 1978, Wardley applied often to Ansett Transport Industries — who ignored her, yet accepted 10 male instructors into their pilot training program. In 1978, Ansett Transport Industries masqueraded their disinterest by interviewing Wardley, but found reasons not to hire her. Knowing her qualification equaled those of the males hired by Ansett, she appealed to the State of Victoria’s Equal Opportunity Board, created in 1977, to assess alleged discrimination based on marital status and gender.

Her landmark case, Deborah J. Wardley v. Ansett Transport Industries (Operations) Pty Ltd., was the first gender discrimination in employment case this board contested. Although 69-year-old aviation tycoon Reg Ansett denied charges of discrimination, he publicly declared, “…while some females might be able to fly airplanes, they were unsuitable as pilots for airline operations.”

Ansett believed an all-male pilot crew was safer, more efficient, and without physical limitations that would permanently or temporarily influence their ability to perform as pilots. In his opinion, women’s limitations included, but were not limited to, inherent insufficient strength and debilitating menstrual cycles. His primary argument targeted pregnancy and childbirth, contending the lengthy disruption of a woman’s ability to perform flight duties would jeopardize safety and incur postpartum re-training costs for the company.

After a prolonged battle, the Equal Opportunity Board ruled Ansett’s refusal to employ Wardley illegal. The government ordered Ansett to include her in the next training program. Instead of abiding by the legal directive to hire Wardley, Ansett launched an appeal to the Supreme Court of Victoria — and delayed intake and training of all new pilots. When this court dismissed the appeal, the company launched an appeal to the High Court of Australia.

Ultimately, this also would be defeated, but Ansett Transport stalled in the interim. Ansett included Wardley in a training program but attempted to expel her based on false allegations, a ploy squelched by the pilots’ union. After classroom training, her male colleagues proceeded to flight training whereas Wardley’s name did not appear on any training schedule.

Fortuitously for her, one of her flight students had been John Calvert-Jones, brother-in-law of Rupert Murdoch who, with Sir Peter Abeles, acquired Ansett Transport in 1979. Calvert-Jones learned of her predicament and told Murdoch, who arranged flight training for her. Within a fortnight, she became the first female pilot employed by a major Australian airline. On her first flight, she flew as co-pilot on a Fokker F27. In the next decade with Ansett, Wardley flew the McDonnell Douglas DC-9, Boeing 727 and 737.