Estimated reading time 11 minutes, 8 seconds.

One hundred years ago, an intrepid group of Canadian aviators completed a significant nation-building effort – the first crossing of Canada by air. The flight began at Canadian Air Board Station Dartmouth, N.S., at 8 a.m. on Oct. 7, 1920, and touched down at Minoru Park Racetrack in Richmond, B.C., at 11:25 a.m. on Oct. 17 — having flown nearly 5,400 kilometres (3,355 miles) in 10.5 days and logging just over 49 hours of flying time.

This noteworthy accomplishment needs to be viewed in context. The First World War had recently finished, and a new combat arm, the Air Force, had been born over the fields of Flanders, the deserts of the Middle East and the trackless wastes of the Atlantic and North Sea. Canada played a significant role in achieving victory in the air as more than 20,000 young Canadian men took to the skies. Though they did so as part of the British Flying Services and not as part of a Canadian military air service.

As Canada approached the end of the war, it became apparent that a national aviation policy had to be developed. Accordingly, the Canadian Air Board, a department of the Dominion government, was established in 1919 to oversee the development of aviation in Canada. The Board not only had to develop a regulatory framework for aviation from first principles, but also had to accommodate two competing visions (civil and military) for the future of aviation in Canada.

It was quickly realized that to survive, the Air Board would have to demonstrate the utility of aviation to the Canadian public and, perhaps more importantly, to Canadian politicians. It is evident that the Air Board’s senior staff — nearly all veterans of the First World War and, therefore, accustomed to risk — seized on the idea of a transcontinental flight to achieve their objective.

Following an internal request in early August 1920, approval was given by the board to carry out a transcontinental flight using relays of aircraft to be flown from Halifax to Vancouver.

Responsibility for the flight was divided between the Air Board’s three branches: the Certificates Branch to organize ground facilities from coast to coast; the Flying Operations Branch to fly the first part of the flight between Halifax and Winnipeg using seaplanes and flying boats; and the Canadian Air Force (CAF) to fly the Winnipeg-Vancouver section using landplanes. Aircraft for the flight were provided from the so-called ‘Imperial Gift’ of war-surplus aircraft donated by the British Air Ministry.

Aircrew and technical personnel were selected from the Flying Operations Branch and the CAF — at this time a non-permanent, non-professional air militia under the control of the Air Board. LCol Leckie, as the superintendent of the Flying Operations Branch, chose to fly the leg from Halifax to Winnipeg with Squadron Leader Hobbs as his co-pilot. Air Cmdre Tylee, Air Officer Commanding, CAF, volunteered to be a passenger from Winnipeg to Vancouver. His pilots would be Flt Lt Home-Hay from Winnipeg to Regina, Flt Lt Cudemore from Regina to Calgary, and Flt Lt Thompson from Calgary to Vancouver.

Problems with weather and serviceability hampered the trans-Canada flight throughout –particularly during the initial stages. The aircraft chosen for this leg was a Fairey III C, a seaplane designed initially for the trans-Atlantic competition of 1919. Great reliance was placed on the seaplane’s promised range; it was believed to carry out a non-stop flight from Halifax to Winnipeg in 24 hours.

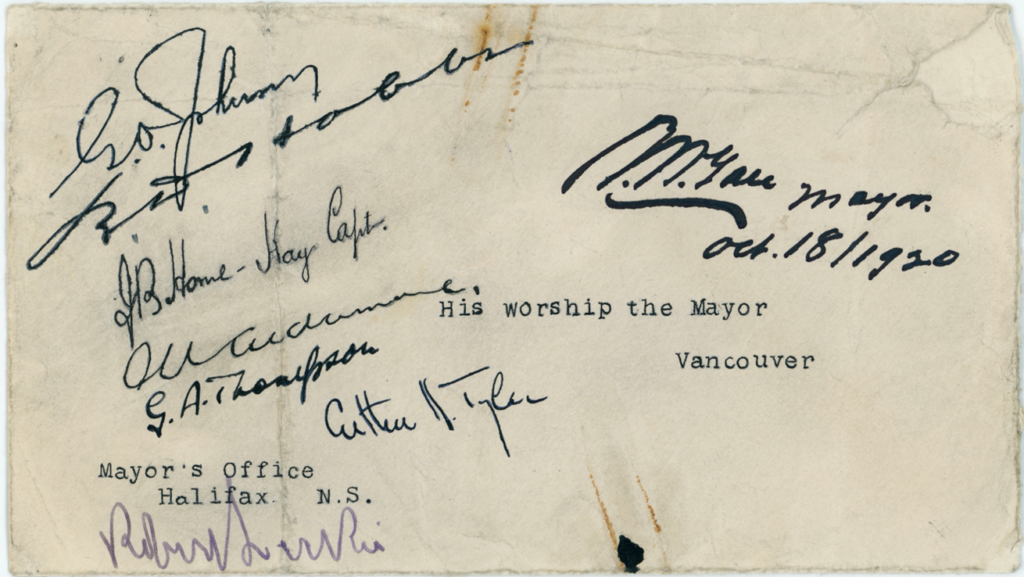

Test flights on the aircraft in Montreal, Que., in late September revealed that the range was nothing like promised, and the planned legs were adjusted accordingly. After several frustrating delays, including weather and technical delays in Fredericton, N.B., Leckie and Hobbs finally landed at Air Board Station Dartmouth on Oct. 5. At this point, letters were loaded on the aircraft from mayors across the country addressed to Vancouver’s mayor. As each leg of the flight was completed, the bag of letters was carefully transferred to the next aircraft in the transcontinental relay.

At 8 a.m. on Oct. 7, the Fairey departed Halifax and headed to Rivière-du-Loup, Que. Alas, the problem-plagued Fairey ran into turbulent weather over the Bay of Fundy and the engine cowling ripped off, striking the externally-mounted fuel pump and dousing Leckie in fuel. A forced landing was carried out on the Saint John River, and the aircraft was so badly damaged it required replacement.

Leckie called up a Curtiss HS-2L flying boat from Dartmouth. Following an exchange of crews, Leckie and Hobbs flew on to Fredericton to refuel and then on to Rivière-du-Loup. Rather than carry on that evening to Winnipeg, the crew wisely elected to spend the night there.

The following morning, Oct. 8, Leckie and Hobbs took off for Ottawa, Ont., onboard a twin-engine Felixstowe F.3 flying boat, which had arrived from Montreal the day before. Engine trouble in Ottawa delayed their departure to Winnipeg until the following day. On Oct. 9, the F.3 arrived at Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., but dense fog precluded the take off. The next day, after leaving the ‘Soo,’ Kenora was reached in the afternoon, and after a short delay to repair a leaking radiator, the aircraft left for Winnipeg.

Following the Winnipeg River to Lake Winnipeg, the crew headed southward along the Red River to a planned landing near St. Vital, Man. Once again, heavy mist precluded a landing, so Leckie opted to land further north on the Red River at Selkirk.

The precious bag of letters was immediately sent on to the St. Charles airfield in Winnipeg where Tylee and his pilot, Home-Hay, were waiting. Their DH.9A took off at 4:30 a.m. on Oct. 11, heading west. Following an unplanned stop in Regina, Sask., due to engine trouble, Tylee changed aircraft there and carried on with Cudemore to Calgary via Medicine Hat, Alta.

The leg from Calgary to Vancouver presented significant challenges, both from the altitude of the mountain passes and the poor weather. On Oct. 12, Thompson and Tylee were weathered in. The following day, they eventually got away from Calgary and headed into the Rockies. They crossed the Selkirks via Rogers Pass, but west of Revelstoke, B.C., they were turned back by heavy snowstorms and eventually landed at Crowle’s ranch.

Oct. 14 was another weather day, but on Oct. 15 the flight continued. After crossing the Monashees via Eagle Pass, they were forced back by fog and landed at Merritt, B.C.

An attempt to cross the Cascades was made the next day, but the airmen were turned back once again. Finally, on Oct. 17, the weather in the Coquihalla Pass opened sufficiently to allow the aircraft to slip into the Fraser Valley in B.C. At 11:25 a.m., they touched down at the Minoru Park Racetrack in Richmond, where the fliers were greeted by the Mayor of Vancouver, R. H. Gale. The precious bag of letters was handed over, at last.

This was not, however, the end of the flight. An impromptu extension to Esquimalt, B.C., was agreed at a celebratory dinner in Vancouver on Oct. 19, where the fliers were urged to continue their flight to Vancouver Island. Leckie and Tylee ‘borrowed’ a Curtiss HS-2L from the Jericho Beach Air Station and took off on Oct. 20 for Esquimalt. Unfortunately, they became lost in the murky weather and eventually were forced to spend the night in Friday Harbor on San Juan Island ,Wash. — American territory.

The crew finally arrived safely in Esquimalt on Oct. 21, and called on the Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia to present letters from the Lieutenant Governors of Nova Scotia, Manitoba and Saskatchewan. And there, the trans-Canada flight finally ended.

The Air Board’s objective of stimulating interest in aviation in Canada proved to be successful. Although the path was neither straight nor smooth, the trans-Canada flight firmly established aviation, both civil and military, in the Canadian psyche.

Please remember these dauntless aviators. They were the pioneers who demonstrated the truth of the statement of former Governor-General Vincent Massey, who said, “The aircraft came to Canada as a godsend. It probably has meant more to us than it has to any other country.”

And it was the trans-Canada flight of 1920 that showed the way ahead.