In 2003, Alberta’s Shock Trauma Air Rescue Service (STARS) made history when it performed a patient transport mission by helicopter under night vision goggles (NVGs) — making it the first civil air carrier in Canada to use NVGs operationally. According to STARS senior pilot Greg Curtis, NVGs represented a solution to a safety problem for the air ambulance provider, which had recently started responding to accident scene calls in uncontrolled (and, often, poorly lit) environments. “There were sleepless nights,” Curtis recalled recently. “We had to bring some closure, some peace of mind to how we were going to operate at night.”

STARS pilots who were flying nighttime missions over Alberta’s prairies immediately appreciated the improvements in situational awareness that came with NVGs. As the organization gained experience with the equipment, it decided it could also use NVGs to develop procedures for safe nighttime operations in the Canadian Rockies. Previously, these 3,000-metre mountains had been off-limits to STARS after dark, but soon pilots were flying through them at midnight to conduct life-saving rescues and medical evacuations. The impact on the organization’s coverage area was profound.

“It’s been so successful. It’s unbelievable, the number of lives that have been affected by the program,” Curtis said of STARS’ operations with NVGs. Moreover, he said, the introduction of night vision technology to the organization remains “one of the most significant things we’ve ever done from a risk and safety perspective.”

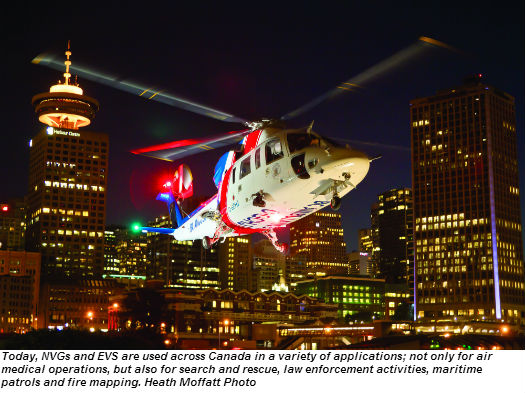

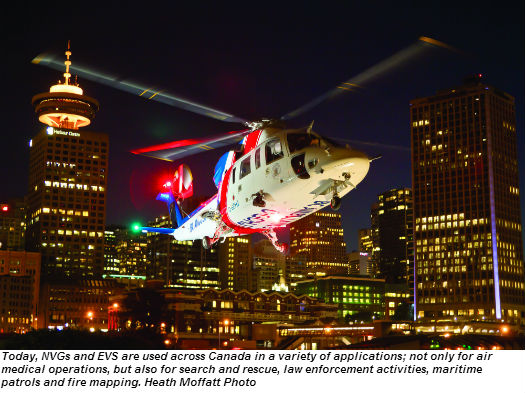

A decade after STARS blazed the trail, an increasing number of Canadian operators have come to appreciate the benefits of NVGs and other night vision imaging system (NVIS) technologies, including enhanced vision systems (EVS), which transmit images from an infrared camera to a display inside the cockpit. Today, NVGs and EVS are used across Canada in a variety of applications: not only for air medical operations, but also for search and rescue, law enforcement activities, maritime patrols and fire mapping. Although NVIS technology is still less common in Canada than it is in the United States, Canadian operators continue to adopt it steadily. They have also taken a strikingly professional approach throughout this adoption process, voluntarily seeking out the best equipment and industry practices, even in the absence of a firm regulatory framework.

“The credit has to go to industry. The operators in my opinion have done an amazing job,” said Transport Canada inspector of flight standards Stephane Demers, expressing hope that this trend will continue as more Canadian operators come to appreciate the safety potential of NVIS. Indeed, he said, “My personal goal is that in a few years it would actually do away with unaided night VFR [visual flight rules operations] in areas with very little cultural lighting.”

ADOPTION PROCESS

Developed as a military technology, night vision goggles were adopted by U.S. Army aviators in the 1970s, but it was several decades before they found their way into the commercial aviation sector. In the 1990s, the U.S. air medical operator Rocky Mountain Holdings (now part of Air Methods Corp.) sought permission to use NVGs from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), which responded with some hostility and suspicion. It wasn’t until the end of the decade that Rocky Mountain Holdings obtained approval to conduct NVG operations; once it did, the rest of the U.S. air medical industry was quick to follow its example. Today, NVGs are ubiquitous in the United States’ large helicopter air ambulance sector, as well as in that country’s airborne law enforcement operations.

NVG technology was a little slower in coming to Canada, in part because of International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) restrictions that complicate the process of exporting it from the U.S. However, it’s also true that the concept of commercial NVG operations was just as foreign to Transport Canada as it had been to the FAA. Demers recalled that, when STARS approached Transport Canada for permission to use NVGs, “we really didn’t have anyone who understood what NVG or NVIS stood for.” Still, the regulator recognized that what STARS was proposing “made a lot of sense,” and it worked with the organization to develop a framework for NVG operations.

Other operators soon put in their own requests for NVG approval, including the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). RCMP chief pilot Jacques Giard told Canadian Skies that the RCMP’s NVG program started in Comox, B.C., where RCMP pilot Scott Healey began working with the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) to learn more about NVG operations. With RCAF guidance, the agency developed a plan for NVG implementation, and certified its first aircraft for night-vision operations in 2006. Today, five of the RCMP’s seven Eurocopter AS350 B3 AStar helicopters, and both of its Eurocopter EC120Bs, have been modified for NVG operations. Most of its helicopter pilots have now received advanced training on NVGs, allowing them to operate at night in mountainous terrain and other challenging environments. “There are not too many places that the advanced NVG pilots can’t operate, keeping in mind that the main reason for [NVG] use is to improve safety during night missions,” Giard said.

The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (MNR) was another early adopter of NVGs. According to MNR Aviation Services operations manager Bob Crowell, the MNR’s chief pilot at the time, Don Filliter, worked closely with the National Research Council (NRC) of Canada to, first, identify potential uses for NVGs, and then develop a plan for implementation. “We looked at where night vision goggles could be used within Ontario,” said Crowell. “We had some support within our management group to prove the concept.” One immediately obvious application was in patrols for illegal nighttime hunters – missions that the organization was already performing, in a limited way, unaided. MNR also identified potential for NVGs in fire mapping, spotting and night suppression; in supporting search and rescue missions with the OPP; and in conducting nighttime medical evacuations of firefighters. With a compelling case for the technology in hand, MNR obtained financial support from the Ontario Public Service Ideas and Innovation Fund, which enabled it to commence NVG operations in 2007.

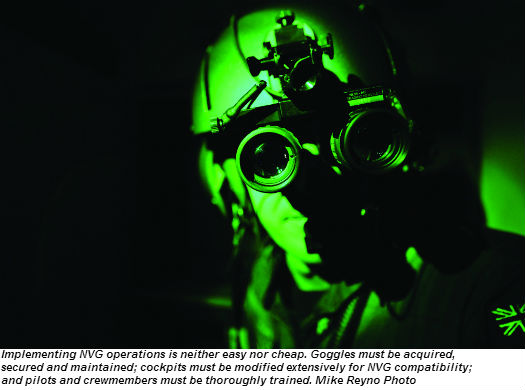

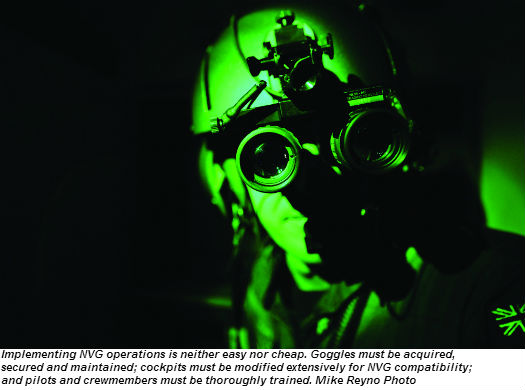

Implementing NVG operations is neither easy nor cheap. Goggles must be acquired, secured and maintained; cockpits must be modified extensively for NVG compatibility; and pilots and crewmembers must be thoroughly trained on the equipment. Recognizing the need for detailed guidance on NVG and other NVIS operations, Transport Canada began working with operators and industry associations to develop a set of relevant guidelines. That effort culminated in February 2012 with the publication of Advisory Circular 603-001, which outlines recommendations for NVIS equipment, aircraft lighting, training and flight crew requirements. One proposed recommendation that received considerable attention was the requirement for NVG pilots to also possess instrument ratings, consistent with the in-house policies of early adopters like STARS and MNR. Transport Canada eventually decided against the requirement, on the grounds that it would impose an excessive burden on operators who were not routinely conducting instrument flight rules (IFR) operations. In such cases, said Demers, “I would rather have someone with good NVIS technology and good training, and maintaining currency.”

Although the guidance in the advisory circular is intended to become regulatory at some point, it’s not clear when that will be. Because of staffing and budget issues, Transport Canada has yet to initiate a rulemaking process for NVGs; once it does, that could take several years to complete. In the meantime, Demers said, the industry has done an excellent job of maintaining high safety standards. “We haven’t had any problems with operators refusing to do what we recommend,” he said. “They’re conscientious . . . they’re purchasing good equipment, they’re following the guidance we’ve put out.”

NEW APPLICATIONS

According to Demers, there are now more than a dozen civil operators in Canada using NVGs. Although the pace of new adoptions has slowed somewhat, Demers said there are still one or two new requests for approval for NVG operations each year. “It’s only going to grow in popularity,” he predicted. Richard Borkowski, president of the Texas-based NVG modifications firm REBTECH, concurred. REBTECH conducted cockpit modifications for many of the country’s first NVG users (including the RCMP, OPP and MNR) and continues to have a strong presence in Canada through a relationship with VIH Aerospace. “I think it’s still a very good market for us,” he said.

One recent adopter of NVG technology has been Cougar Helicopters, which last year decided to add NVG capability to its offshore search and rescue (SAR) program in Newfoundland and Labrador. “In the past we were doing night support, but it was really limited to going out and hoisting off a rig,” said Cougar SAR chief pilot Wayne Timbury. Cougar realized the potential of NVGs to expand its mission capabilities, and turned to VIH to complete the necessary cockpit modifications on both its primary and back-up Sikorsky S-92 SAR helicopters. For training and operational guidance, it tapped into the expertise of Texas-based night vision solutions provider Night Flight Concepts. Crews began training on NVGs in January; at press time, approximately 80 per cent of them had been qualified on the devices. Although performing offshore SAR missions under NVGs is without doubt a demanding proposition, Cougar’s SAR program is aided by a generous training budget: “Basically every night the weather’s good, we do a training flight,” said Timbury.

The Idaho-based night vision company Aviation Specialties Unlimited (ASU) played a key role in two other groundbreaking NVG projects in Canada. One of these was working with British Columbia’s Coulson Aviation to modify a Sikorsky S-61 helicopter for NVG operations, with an eye toward nighttime aerial firefighting, a practice that is already widespread among public-use helicopter operators in Southern California. Coulson has developed an innovative system for ensuring accurate water drops at night using its Sikorsky S-76B “FireWatch” helicopter, which is equipped with an Axsys Technologies V9 multi-sensor camera system, an infrared laser designator and an AeroComputers moving map system. This command-and-control aircraft identifies areas for water drops and highlights them with its laser designator, which is visible to the

S-61 pilots under NVGs.

“The S-61 flies right to the laser, does its drop and leaves,” explained the company’s Britt Coulson. “It’s a very clean system, requires no run descriptions and maintains a sterile radio environment.” The company expects to demo the system in Australia this year, and it is also in discussions with various U.S. states about employing the technology there. According to Britt Coulson, however, interest from Canadian forestry agencies has been lukewarm at best, so the company expects to introduce the system outside Canada first.

ASU also worked with Provincial Aerospace Ltd. out of St. John’s, N.L., to modify a Beechcraft King Air 200 for NVG operations, achieving simultaneous Supplemental Type Certifications from Transport Canada and the FAA late this summer. As Provincial Aerospace’s vice president of aerospace services Jake Trainor noted, there tend to be more applications for NVGs within helicopter operations, because of helicopters’ ability to operate away from lit airports. However, Provincial Aerospace, which performs maritime surveillance for a number of Canadian entities, saw the potential for NVG technology in this special mission role, which requires nighttime maneuvering at relatively low altitudes. “It is another tool that can be added to the box,” Trainor said of the use of NVGs. “It increases effectiveness and safety.”

Although NVGs remain the best known and most widely adopted NVIS technology, an increasing number of operators are also coming to appreciate the advantages of EVS, either used alone or in conjunction with NVGs. Bob Yerex of the EVS company Astronics Max-Viz praised Transport Canada for taking the lead in developing guidance for EVS implementation (something that is still comparatively lacking in the United States). Indeed, Transport Canada has taken an intentionally broad-based approach toward developing NVIS guidance – one that should be able to accommodate future as well as existing night vision technologies. “They’re looking objectively at, what is the problem and what are the solutions available?” said Yerex.

The Government of Manitoba’s Air Services Branch is one of the Canadian operators using EVS, although it has encountered a few hiccups in implementing the technology. According to the Branch, the province had dual sensor EVS systems installed on its two Cessna Citation 560s, which are used for medevacs. However, it discovered that the fairings for the externally mounted cameras caused excessive vibration in flight. The Branch is now waiting on Cessna to develop an improved installation. Manitoba also tested single sensor EVS systems in some of its firefighting fleet, which now includes two Canadair CL-215 and four Bombardier 415 water bombers. Although the single sensor system was found to be an effective aid in seeing drop patterns and operating in reduced visibility due to smoke, it couldn’t find an ideal mounting location for the cockpit display. So, the Branch is now waiting on approvals to upgrade its water bomber cockpits with multi-function displays, which will be able to show EVS video as well as flight information.

Despite these hurdles, the Branch suggests that EVS will assist in their continued safe and effective delivery, and may eventually allow its Citations to conduct reducedvisibility taxi operations at airports where those operations are not currently permitted. The Branch also noted that insurance underwriters have been particularly supportive of this technology in Manitoba’s specialty flight operations.

CALLING ON THE EXPERTS

A common refrain among the operators that Canadian Skies spoke with for this story was the value of seeking expert advice in developing and implementing night vision programs. For their part, NVIS experts praised Canadian operators for their diligence in educating themselves on the technology, with Adam Aldous of Night Flight Concepts calling the Canadian learning culture “one of the best of the world. They don’t have any problem going outside to see what are the best practices.” Implementing night vision operations is such an expensive proposition that most Canadian operators have been willing to invest in doing things right. Expert advice is particularly useful when it comes to U.S.-sourced NVGs, because the consequences of even inadvertent ITAR violations can be devastating.

Commercial operators who want to adopt NVIS technologies should begin by submitting a proposal to Transport Canada, following the guidance in Advisory Circular 603-001 (this is also something with which outside experts can assist). According to Demers, Transport Canada will be looking for a summary of the equipment they want to buy, what types of operations they want to do, and how they intend to accomplish initial and recurrent training. From that point, the pace of the approval process will depend not only upon the completeness of each proposal, but also upon the availability of Transport Canada inspectors with NVIS expertise. Demers acknowledged that Transport Canada currently has a shortage of principal operations inspectors qualified to conduct oversight of NVIS operations, with some regional offices more affected than others. This is a problem that has hampered Fort McMurray, Alta.-based Phoenix Heli-Flight, for example, as it has worked to implement NVGs on a new Eurocopter EC135 air medical helicopter. (In September, Transport Canada advised Canadian Skies that it was working with Phoenix Heli-Flight to resolve the issue.)

NVIS technologies certainly have their limitations. Regarding NVGs, pilot Doug Holtby of MNR cautioned, “The things work so well, it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that there are hazards out there. . . . You can become overconfident very quickly.” Nevertheless, they have made a dramatic impact on the safety of commercial aviation operations in Canada, and have the potential to do even more. Reiterating his personal preference that he’d like to see unaided night VFR operations “go the way of the dodo bird,” Demers observed, “Canada has a lot of night. There are places so dark that you might as well stick your head in a pillow . . . To me, anything is better than black space.”