Estimated reading time 15 minutes, 18 seconds.

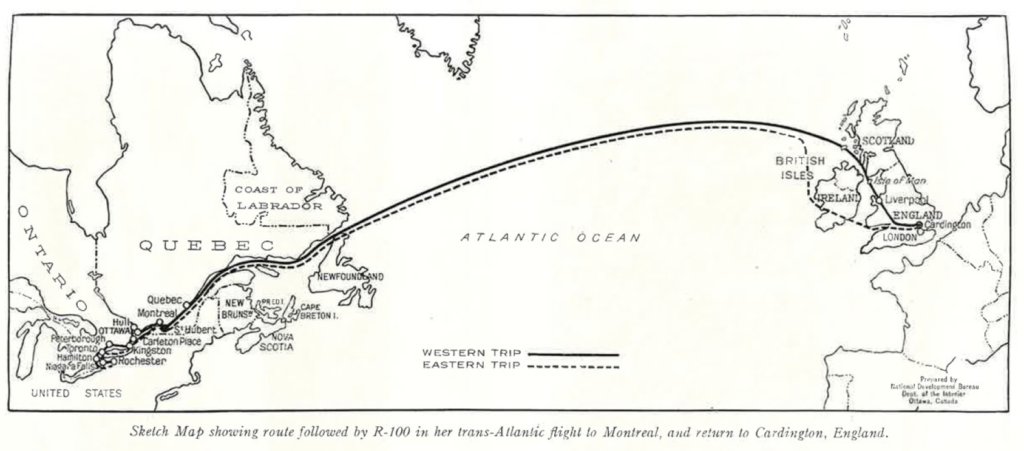

Ninety years ago, almost a million and a half Canadians looked skywards to see His Majesty’s Airship R-100 slowly sail across the sky on a 13-day visit to Quebec and Ontario following a record setting 3,364-mile (5,414-kilometre) non-stop flight from England.

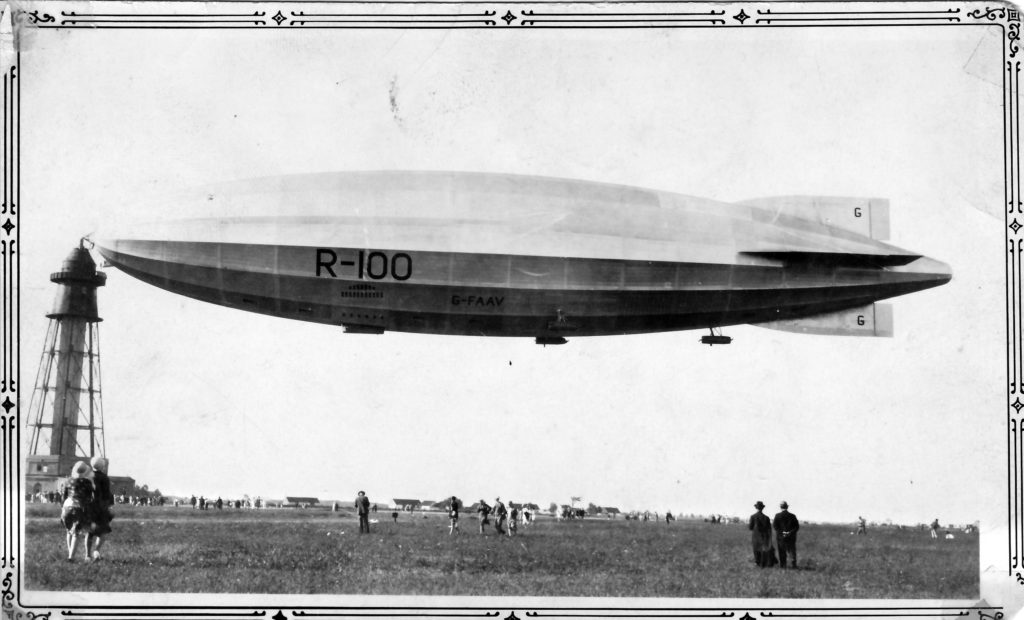

The 719-foot 9.5-inch (219-metre) long R-100 was the largest airship in the world in 1930 (along with its sister ship R-101), and was designed to carry 100 passengers and 37 crew on regularly scheduled mail and passenger flights to Canada, Egypt and India.

The excitement generated by the R-100’s arrival inspired 800,000 people to travel to St. Hubert Airport to view the moored airship, which was three times longer than today’s Boeing 747 or Airbus A380.

The trans-Atlantic voyage between July 29 to August 16, 1930, promoted the coming age of scheduled airship flights linking Canada and England, but in a twist of fate this never occurred.

Imperial vision

In 1924, the British government sponsored the Imperial Airship Scheme to link the far corners of the Empire with scheduled airship service. The government committed to fund the construction of two airships, one built by private industry (R-100) and the other by the government-owned Royal Airship Works (R-101).

Canadian Prime Minister MacKenzie King was briefed at the Imperial Conference in London in 1926 and made a commitment to build an airship base in Eastern Canada to support regular trans-Atlantic mail and passenger service.

A second airship route to India resulted in the construction of an airship mast in Ismailia, Egypt, and a mast and hangar in Karachi, India (now Pakistan).

St. Hubert Airport

The next year, a British team came to Canada to help select a suitable site.

At the time, the Canadian government believed that communities and aviation companies should build their own airports. The government tried to convince the City of Montreal to construct an airship base and airport, but the city was not interested.

A one-square-mile plot of flat land on the south shore of the Saint Lawrence River with clear approaches was selected for the airship base in August 1927. The location was about six miles (10 km) from the centre of Montreal, four miles (6.4 km) from the Longueuil ferry wharf, and adjacent to the St. Hubert Station on the Canadian National Railway main line and the Chambly Highway.

St. Hubert became the first civil airport built and owned by the Canadian government. The centrepiece of the $1 million development was a 208-ft (62-m) high illuminated, orange and black mooring mast that was a marvel of mechanical ingenuity.

The iconic steel mooring tower was designed by the Department of Public Works in Ottawa and built by Canadian Vickers, which was also actively building aircraft at its shipyard on the Montreal waterfront.

The mast was equipped with an elevator and a circular stair case to the ground to move passengers and crew. It was also equipped with pipes running from the ground to the top of the tower to replenish an airship with fuel, water and hydrogen gas.

The controls in the mast were designed so a mooring officer and an assistant could easily moor giant dirigibles with a set of mechanical controls and winches and the support of a large contingent of staff on the ground.

The ground floor of the tower contained three large rooms filled with huge winches, brakes, transformers and motors. And set back from the airfield was a hydrogen gas plant.

The R-100

The R-100 was built by Airship Guarantee Company, a subsidiary of Vickers, in First World War airship hangars relocated to Howden, Yorkshire.

The airship was designed by English scientist, engineer and inventor Barnes Wallis and used his revolutionary geodetic airframe construction technique. (Wallis is probably best known as the designer of the Wellington bomber and the inventor of the bouncing bomb used in wartime by the RAF’s “Dam Busters.”)

The internal structure consisted of 16 longitudinal girders that connected 15 16-side transverse frames positioned at regular intervals between the nose and the tail, and had a maximum diameter of 133 ft (40 m).

The exterior was covered with linen fabric painted with silver aircraft dope, and the hydrogen gas that provided the lifting power was contained within the airframe in 15 gas cells that had a total capacity of five million cubic feet.

The R-100 was also designed to collect water ballast in flight. This included rain and moisture collected on the upper surface when it passed through clouds, which was funneled to internal ballast tanks. Collecting water inflight helped compensate for the weight of fuel burned by the engines.

Construction of the R-100 started in 1926 and after many delays (primarily caused by labour strikes) the airship made its maiden flight on Dec. 16, 1929.

The bow of the R-100 contained an attachment fitting for the mooring mast, facilities for the transfer of passengers, fuel, water and hydrogen gas, and a crew observation station.

This connected to a 280-ft (85-m) enclosed corridor leading to a three-floor passenger compartment below the gas bags. The top two floors contained 14 two- and 18 four-bunk cabins for 100 passengers, and had promenade decks on the outside that faced huge windows on either side of the airship that provided a spectacular view of the earth. The decks were connected by a large double staircase with the 56-seat dining room and all-electric kitchen on the lower level.

The crew quarters, dining area, captain’s cabin and navigation and metrological rooms were located below the passenger cabins.

The control car attached to the bottom of the airship contained the control wheels for the rudders and elevators as well as the engine controls. It was connected to the crew quarters above by a ladder.

Six 650-horsepower Rolls Royce Condor III engines powered the R-100. These were mounted in three nacelles containing two engines each, with one engine powering a 17 ft (5.18 m) tractor propeller and the other a 15 ft (4.57 m) pusher propeller at opposite ends of the nacelle.

Two nacelles were mounted to the underside of the R-100 about 190 feet (58 m) behind the passenger cabin, and there was a third nacelle 90 feet (27 m) further aft.

Trans-Atlantic Flight

The R-100 departed Cardington, Bedfordshire, for Canada under the command of captain Ralph Sleigh Booth on the evening of Tuesday, July 29, 1930, with 37 crew and six passengers, including deputy chief engineer Nevil Shute Norway (who using his pen name Nevil Shute became a famous novelist).

The ocean crossing was uneventful, and the airship entered the Gulf of Saint Lawrence flying over the Strait of Belle Isle separating the island of Newfoundland and the Labrador Peninsula. On reaching Quebec City, almost every ship in the harbour blew its horn in a welcome greeting. At the time, it took at least five days to sail between Quebec City and Southampton.

The R-100 was forced to reduce its speed flying up the Saint Lawrence towards Montreal after some violent winds tore some of the fabric covering off the tail fins. The R-100 reached Montreal at night.

Then at 4 a.m. on Friday, Aug. 1, the crew dropped a mooring line from the nose and two yaw lines from the rear of the R-100 as it floated 500 ft (150 m) above St. Hubert Airport.

The mooring line was attached to a cable attached to the telescoping receiving arm at the summit of the mast, and the yaw lines passed through heavy pulleys attached to two of 24 cement anchors ringing the mast at a radius of 740 feet (225 m).

Three winches then pulled the R-100 towards the mast until fasteners attached to the receiving arm and to the nose of the airship snapped together at 5:37 a.m., marking an end to the 78-hour and 49-minute flight — eight hours of which were attributed to the damage suffered over Quebec.

St. Hubert welcomes fans

More than 200 journalists and photographers were on hand to report on the arrival of the R-100. Official commentary was provided in English and French only after pressure was apply by local French language newspapers and Quebec Members of Parliament.

Local newspapers reported that the R-100 was 215 ft (65 m) longer than the White Star Line’s SS Laurentic, which was the largest ocean liner serving Montreal in 1930.

Nearly 800,000 people journeyed to St. Hubert to view the R-100 during its 13 days in Canada, including 3,000 who were able to tour the mooring mast and the airship.

A train station was specially established in downtown Montreal, and on Saturday, Aug. 2 alone nearly 150,000 people took the train to the airport. The Quebec government also recorded that 131,977 cars visited the airport during the R-100’s stay, carrying half a million people.

Visit to Ontario

It’s estimated that another million Canadians viewed the R-100 on its 26-hour flight over Ontario on Aug. 10 to 11, 1930, with 16 VIP passengers from the government, military and industry. The route took the R-100 over Ottawa, Kingston, Peterborough, Oshawa, Toronto, Niagara Falls, St Catharines, Hamilton, Burlington, Gananoque, Prescott and Cornwall.

In Toronto, local newspaper photographers photographed the R-100 over the city from the roof of the Bank of Commerce building on King Street.

Photos published during the 1930 visit showed female kitchen and dining room staff, but no women were flown onboard the R-100 during its visit to Canada.

The R-100 departed St. Hubert mooring tower at 9:30 p.m. on Wednesday, Aug. 13 and arrived in Cardington, U.K. at 11:06 a.m. on Saturday, Aug. 16 after a flight of 57 hours and 56 minutes. On the return flight to England there were 16 passengers including 10 Canadian and British journalists.

Tragedy

The spotlight then shifted to the R-101, which was scheduled to make its maiden overseas voyage with a flight to Karachi (then part of British India), with a refuelling stop at Ismailia, Egypt.

The R-101 departed Cardington on Oct. 4, 1930, at 6:36 p.m. GMT and sailed towards France in deteriorating weather. Then at just after 2 a.m. GMT over France, the airship went into a sudden dive and lost around 450 ft (140 m) shortly followed by a second dive where it hit the ground near a forest outside Allonne, southeast of Beauvais, and burst into flames.

The R-101 crash killed 48 of the 54 passengers and crew onboard, including four officers and four crewmen who had flown to Canada on the R-100. Also killed were many of the leaders of the British airship program as well as Lord Thomson, the Secretary of State for Air in parliament.

The probable cause of the crash was loss of forward buoyancy, due to weather-induced damage, causing the nose to pitch down violently followed by a hot engine contacting extremely combustible hydrogen gas leaking from the airship. The pressure to depart in less than ideal weather was an underlying issue contributing to the crash.

One year later, the Imperial Airship Scheme was cancelled, and the magnificent R-100 was ordered scrapped.

Postscript

St. Hubert Airport became the centre of civil aviation in eastern Canada. It was the first airport lighted at night; the first with a radio range; the first with a control tower; and the first with snow removal.

The airship mooring mast was dismantled in 1938 and St. Hubert became a military airport after Montreal’s Dorval Airport opened on Sept. 1, 1941.

In 2007, Montreal aviation historians located many of the 24 concrete airship mooring blocks on the airport property as well as a tether ring, which is now part of a collection of the Montreal Aviation Museum. The 438 Tactical Helicopter Squadron at St. Hubert has a 10-foot (three m) wooden propeller made in Montreal to replace a damaged R-100 propeller, but it was never used.

The Quebec Aerospace Museum says the location of the iconic R-100 mooring mast (coordinates 45 31 13.59 N 073 25 20.46 W) placed it on the airfield about halfway between the 438 Squadron hangar and the L’École nationale d’aérotechnique (ÉNA) campus.

Hi Ken; Nicely detailed description of the R100’s visit to Canada. On my website I have the “Muddy York Tours” presentation of same . Not quite as extensive as your piece.

Cheers, Bob

This is a very interesting and factual account of the R-100 flight to Canada. There is a part of this description that may be misleading, if untrue. The statement that the airship accident caused it to “pitch down violently followed by a hot engine contacting extremely combustible hydrogen gas leaking from the airship.” That hydrogen burns is fact, but when it caught fire is important. If after the crash, then it is not a cause and vice versa. It is hard to get such a light gas to contact engines near the bottom while in the air. Any leaking hydrogen goes straight up.

The R 100 on it’s Ontario flight was to fly down the Humber River to the Place Pier in Toronto at lake Ontario. This was not the case as it flew down the Credit River to The grain mills on the Credit river Streetsville Ontario. Here it got caught in a down draft and hit the trees with the aft engine rudder area ripping off some branches astonishing, some people swimming here at the moment! The engines were gunned and the R100 rose to just clear the south embankment trees located here and disappear . I learned this from the shocked people who witness this while swimming at the” Old Swimming Hole ” Streetsville Ontario. I also have a photo post card of the R100 at this moment.

That is simply not true. Fake story.

hello gentle men , i have a piece of the R 100 , my grandfather was a Captain sailed out of Montreal in the 2os and thirtys Capt Ralph P Fuller he was in 1st World War and the Second ,he may have been a guest on the Flight across Ont , the fabric is silver on the out side and red on the inside in perfect condition ,he had it in a envelope on the inside he wrote his intials and a date R.PF. R-100 may 22 1932 ,i never new what it was till i typed in what it said on the fabric and up came all about who and what it was from ,he passed never met him so was clueless untill the internet .now i no ,he sailed all around the world working out of montreal on a steam ship

I am told that my father’s brother, Paul Reading, crossed the Atlantic on the R-100 as the only newspaper man aboard her on that maiden flight to Montreal. He’d likely have done so at the behest of the Toronto Star and Weekly Herald..

Be interesting to see crew and passengers names from that initial flight.

My grandfather crewed the 1930 R100 crossing to Montreal. I have several photos. My grandmother was a seamstress who worked on the airship itself. I myself am from the UK but happened to end up living here in Canada.