Estimated reading time 9 minutes, 48 seconds.

History is rarely as simple as we wish it would be, with tidy narratives that begin and end in places everyone can agree upon, with facts that are never in dispute and interpretations that form an eternal consensus.

But in history there are often touchstones whose significance is clear–events that help us understand who we are in the present, how we got here, and where we may go in the future.

In Canadian aviation, one of those touchstones is the story of the Ruhr Express, the first Lancaster bomber built here, part of an ambitious program that not only helped win the Second World War but contributed to the formation of a modern aviation industry that is among the best in the world.

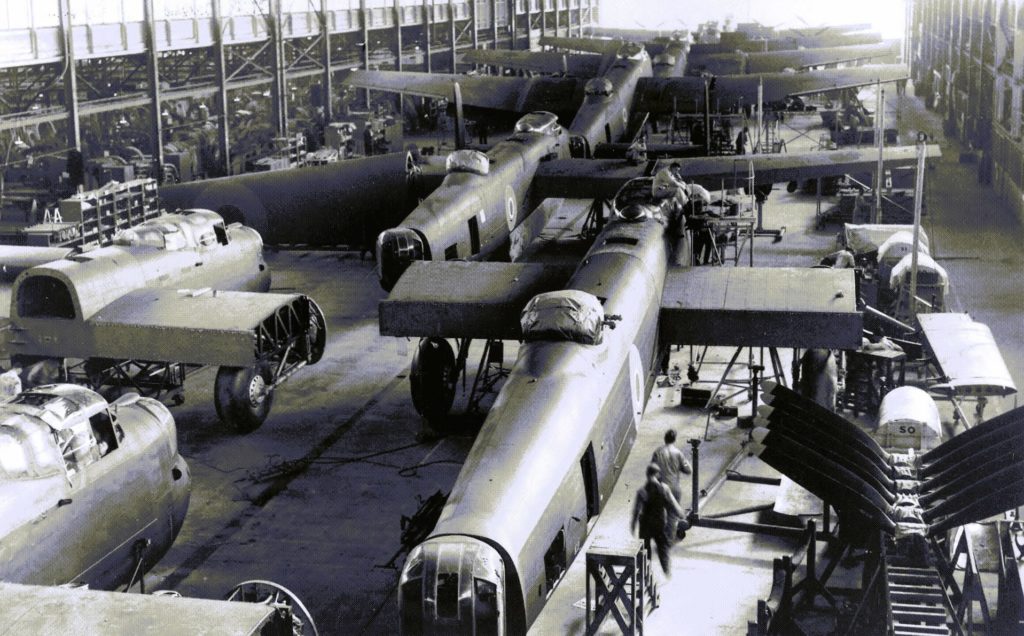

Built in the space of about 16 months in the early 1940s, the Ruhr Express was the first of more than 420 Lancasters built in Canada during the war, according to K.M. Molson and H.A. Taylor’s Canadian Aircraft Since 1909, a survey of major achievements in the Canadian industry.

The aircraft division of Montreal-based National Steel Car, a company known for making rolling stock for railroads, initially spearheaded the Lancaster program, according to literature from the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum (CWHM) in Hamilton, Ont.

But various concerns led the Canadian government to expropriate the company and form a Crown corporation known as Victory Aircraft Limited that built Lancaster bombers at a relatively small factory in Malton, Ont.

Canadian Lancasters were designated Lancaster Mk. X, and were originally to be equivalent to the British Lancaster Mk. III, but with North American instruments, radios and ball bearings from the United States, according to Molson and Taylor. A completely new wiring system was also added, contributing to headaches for ground crews that trained on British versions of the aircraft.

Canada’s Lancaster program was a massive undertaking that sprang up quickly, and it required contributions from outside Victory Aircraft.

While most components were initially tooled and built at the Malton plant, the bomb doors, flaps, ailerons and elevators were built by Ottawa Car & Aircraft Limited, according to Molson and Taylor.

Many components were later subcontracted out, with Canadian General Electric Co. Ltd. in Toronto making fuel tanks, tailplane, fins and rudders. The aircraft’s outer wings were later subcontracted to Fleet Aircraft of Fort Erie, Ont., an early example of the collaboration that helps define Canada’s modern aviation industry.

The Ruhr Express, also known as Canadian Lancaster prototype KB700, first flew on Aug. 1, 1943 in Malton, with a christening ceremony on Aug. 6 attended by most of the Victory Aircraft workforce and broadcast on radio across Canada.

It arrived in Britain on Sept. 15 and made its first attempted raid on Berlin on Nov. 22, but engine failure required it to turn back short of the target, according to Molson and Taylor.

This was one of many mechanical problems that plagued the Ruhr Express, though David Clark, an amateur historian with the CWHM, noted such problems were not uncommon in new aircraft, “especially in the first aircraft off the production line of a new factory that had gone from blueprints to production with such speed.”

Initially part of the Royal Canadian Air Force’s 405 Squadron, it was reassigned to 419 Squadron at the end of April 1944, according to Molson and Taylor.

The Ruhr Express was perceived as slow and difficult to fly, likely due to the fact it was the first aircraft in an upstart program with a long service life, as well as differences between Canadian Lancasters and their British equivalents that made maintenance difficult. A successful flight in the Ruhr Express became a badge of achievement for older crews and a rite of passage for newer ones within the squadron, said Clark.

Still, the aircraft was a workhorse that flew 49 missions before it crashed after landing at an airfield on Jan. 2, 1945. There are differing accounts of the crash, but historians agree the aircraft collided with heavy equipment on the ground, caught fire and never returned to service.

The legacy of the Ruhr Express and Canada’s Lancaster program is considerable. It was part of a Canadian aviation industry that employed about 116,200 people at its height in 1944 and produced thousands of combat and training aircraft, including Lancasters, Mosquitos, Hurricanes, Cansos, Helldivers, Bolingbrokes, Lysanders, Ansons, Harvards, Cornells, Tiger Moths and Norsemen, said Clark.

After the war, production at Victory Aircraft reduced dramatically, along with its workforce. But the company continued to play a crucial role in the aviation industry after it was sold and re-named A.V. Roe Canada Limited.

Better known as Avro Canada, the company went on to produce Canada’s first domestically-designed and built jet fighter aircraft, the CF-100 Canuck. It is perhaps best known for the Avro Arrow fighter interceptor program, which the government controversially cancelled in 1959.

While the loss of the Arrow is seen as a symbol of what Canada’s aviation industry may have become, the Ruhr Express helped lay a foundation that made such ambitious projects possible.

“Canada’s aviation industry barely existed in 1939 but by the early 1950s the country had one of the world’s finest aerospace industries, which was an incredible achievement in such a short period of time,” said Clark in an interview with Skies. “Ruhr Express and Victory Aircraft were a major part of that development.”

This summer, the CWHM is taking steps to ensure this story is not forgotten. The museum is altering the port side of the Lancaster in its collection to resemble the Ruhr Express, using a temporary vehicle wrap–similar to those seen on cars, buses and airliners–to mimic the Ruhr Express paint scheme.

Visitors will be able to fly in the altered Lancaster over the summer and see it on static display. This is the latest in a series of temporary modifications the museum has used to highlight notable Lancasters.

“Although we’re not going coast to coast with the aircraft, we are going to be able to complete the story by showing off the aircraft that was produced at Malton,” said Al Mickeloff, marketing manager for CWHM.

For more information about the museum’s Lancaster project, and to read Clark’s history of the Ruhr Express and other notable bombers, visit www.warplane.com.

Extremely interesting report on the ‘ CWHM Lancaster ‘ , the Ruhr Express . I , personally, would like to visit Canada (again ) , one day , &enjoy a Flight in one .

The aircrew standing next to KB700. The FSGT on the far right is Michael Bachinsky, flight engineer on the trans-Atlantic ferry flight to UK.. He enlisted

under his polish surname name, but later in life converted it to English so others could pronounce it easier. He recalls the ferry flight was unremarkable except when an engine began acting erratic. He hit the Pesco pump to increase the supply of fuel and the engine purred normally there after. A National Film Board of Canada cine photographer gave Mike a reel of 35mm film. Bachinsky bought a 35mm camera in England, cut and spooled his own film, and took photos while stationed with 431 Squadron. He had 200 negatives taken at Croft showing his crew, the bombers, ground personnel loading ordnances into the bomb bay, flight line sequences, life-raft training in a swimming pool, the enlisted mens’ mess, building and hangars. He even took daylight photos of 431 Lancs flying loose formation bombing targets in Germany. When 6 Group returned to Canada, he took photos of Lancs and other RCAF aircraft at a base in Nova Scotia.

Mike originally served with 44 Squadron as a flight engineer with Rhodesian pilot Happy Taylor in 1943. The crew was one of the first to complete 25 ops over Germany–truly a rare event at this period of the war. During one mission, returning to England, their Lanc collided mid-air with a Sterling bomber at night flying low over Denmark to escape nightfighters. Both damaged aircraft landed safely in England. Mike received a DFC.

My great grand Uncle was Mike Bachinski and have only recently learned of him.

WOW ! lots of unknown History here.

To add to that last photo. The man in the door holding the dog in the kb700 is my grandfather Reginald burgar. He was the tail gunner. He served with the 419th.

My great uncle Michael Bachinski is under the two 00’s.

The man in the door holding the dog, Bambi,is also my grandfather Reginald Burgar.

My father was a navigator in 408 F/O W.R. Arnill DFC He knew the pilot who flew the Ruhr Express and told me it was no accident the day it came back from a raid and its landing gear “accidentally ” didn’t go down and the plane never flew again.

According to the text above, Reg Lane is listed as the pilot who ferried KB700 to Prestwich, Scotland. According to Michael Bachinski’s log book, he lists the pilot he sat next to who ferried KB700 as Clyde Pangborn, an American Ferry Command pilot. They flew directly from Gander to Scotland on the nighttime 9:30 hour flight.

My great grand uncle was Michael Bachinski and was wondering if I could see his log book and photo’s he took? Mike received a DFC. I don’t know what that is?