Estimated reading time 7 minutes, 54 seconds.

“Turbulence” and “trouble” are a few pages apart in most dictionaries, but there’s a case for having them listed sequentially in the lexicon of aviation, because the costs of turbulence to the industry are troublesome.

According to NASA, turbulence can cost commercial aviation over US$100 million annually. This is due to crew and passenger injuries, unscheduled maintenance, revenue lost when aircraft are taken out of service, and operational inefficiencies.

Add to that the incalculable costs to private, corporate and military aviation, and the potential total emphasizes the need for more accurate ways to predict turbulence.

The Weather Company, an IBM Business, says studies have shown that encounters with turbulence are the leading cause of non-fatal injuries in commercial aviation.

In July, for example, turbulence contributed to 24 injuries on a JetBlue flight in the U.S. and to three injuries aboard a flight into Billy Bishop Toronto City Airport. Anecdotally, litigation is increasingly common even though passenger injuries are often attributable to a failure to heed crew warnings. Even if carriers win in court, costs aren’t always awarded in their favour.

Increasingly aware of the financial as well as meteorological risks, a “who’s who” of international carriers appreciates the value of more and better forecasting—which brings The Weather Company into the picture. Billing itself as the world’s “largest private weather enterprise,” The Weather Company delivers an average of 20 billion forecasts daily.

“We have 140 carriers globally that are relying on at least part of our platform and service,” senior vice-president Mark Miller told Skies. “They include 45 of the top 100 global carriers, so we’re more than just a North American company.

“Our focus tends to be on large to mid-size carriers. . . . with more complex networks where weather can have a really significant impact on overall business performance.”

The Weather Company, which includes a global business-to-business division and consumer brands, The Weather Channel and Weather Underground, was acquired by IBM last January. IBM did not acquire the cable TV/broadcast business.

“It’s been a great evolution,” said Miller. “I have seen a lot of change and I’ve seen our position in the market, our value proposition to our clients, develop quite a bit.”

With a BSc in meteorology, a strong background in computer science, and a master’s degree in engineering management, Miller has worked across the spectrum of the company’s markets, but has focused on aviation for the last 15 years.

The Weather Company has no fewer than 40 aviation meteorologists, many based in the Andover, Mass., office, where the business solutions division is headquartered, and others embedded within airlines.

“Our value has always been around enhanced weather services to support better decision-making,” he continued. “We’ve evolved to become an essential platform for commercial flight operations, with our key value being improvements in safety, efficiency and performance. . . . But what we do now with airlines goes well beyond weather. We have a platform and a suite of applications that are used within the airline operation to basically manage flights from pre-flight through to touchdown.”

While individual carriers can have different standards for turbulence advisories, The Weather Company forecasts can reach out 24 hours. “So even for a long-haul flight from, say, Houston to Dubai (the Emirates Airbus 380 takes nearly 17 hours to cover 13,140 kilometres), they have guidance for the whole flight.”

This is augmented by carriers’ own dispatchers, air navigation service providers, and the aircraft’s own radar. “Through a combination of sources, including our own application and services, they can readily identify potentially hazardous areas,” said Miller.

“We’re basically aggregating as many observations from aircraft as we can. . . . Those come into our [facility] from aircraft, where we present it to our aviation meteorologists who then can continually update and revise their real-time and forecast guidance. Whenever we get a new turbulence report, we can automatically alert aircraft traversing that area.”

In this case, “real time” really means that within 30 to 60 seconds of receiving an observation from one aircraft, it’s accessible to other pilots, including the growing number with tablets in the cockpit.

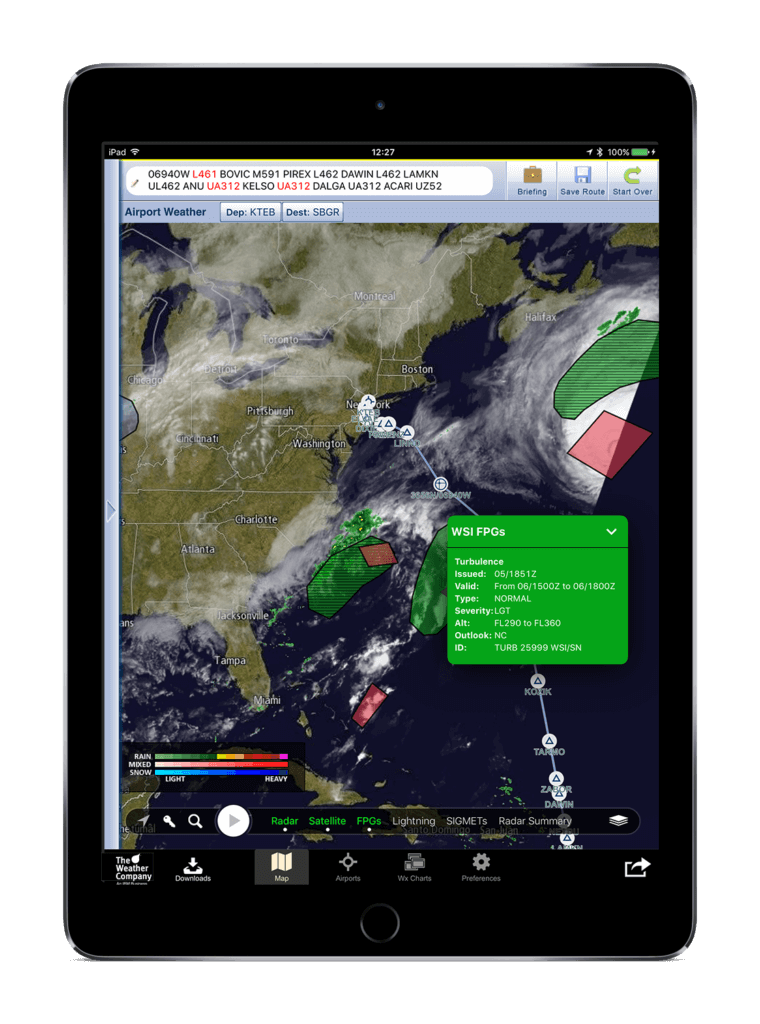

“If they have that connectivity, we display it on Pilotbrief, our iPad app, which provides both the real-time report as well as our forecast guidance, all displayed relative to their flight plan and other relevant information.”

It also can offer rerouting options.

The Weather Company upped its game in June when Mark Gildersleeve, president of business solutions, confirmed that Chicago-based Gogo—a leader in in-flight connectivity with installations aboard more than 2,500 aircraft in 17 commercial fleets and more than 6,800 business aircraft—would use The Weather Company’s patented Turbulence Auto PIREP System (TAPS), which has already yielded a reduction in turbulence injuries and maintenance calls.

Essentially a turbulence-detection algorithm (a stand-alone set of calculations and/or data processing used to “automate” larger functions); the TAPS resides on Gogo’s server. Aircraft-generated data is used to create turbulence intensity reports for dissemination on Gogo’s air-to-ground and global satellite communication network.

“Leveraging Gogo’s expanded fleet of aircraft, The Weather Company can quickly share real-time turbulence data directly with pilots and dispatchers,” Gildersleeve told the The Weather Company’s aviation conference in Cambridge, Mass. “It is a great example of the Internet of Things (IoT) in action, where we are collecting massive amounts of data very quickly and then using that insight to provide guidance to all flights.”

Going forward, The Weather Company will continue to expand its network and improve its weather modelling capabilities. Miller said IBM is an industry leader in IoT, collecting data from a wide array of devices and sensors ranging from vehicles to buildings in order to improve forecasts and inform better decisions.

“The more data you have assimilating into a numerical weather model, the better the forecast,” said Gildersleeve. “Our big push right now is providing the most skillful forecast for these kinds of high-impact events, so that’s an area where we’ll continue to make our turbulence solution better.”

A lingering challenge is getting The Weather Company’s data integrated into air navigation services, where lead times for new systems tend to be longer.

“It’s more complicated than just providing the data in those environments,” confirmed Miller. “We clearly see an opportunity and as we continue to build out our network and continue to improve our forecast skill around turbulence and our overall system, there are definitely opportunities to help all aspects of the aviation industry.”