Estimated reading time 14 minutes, 10 seconds.

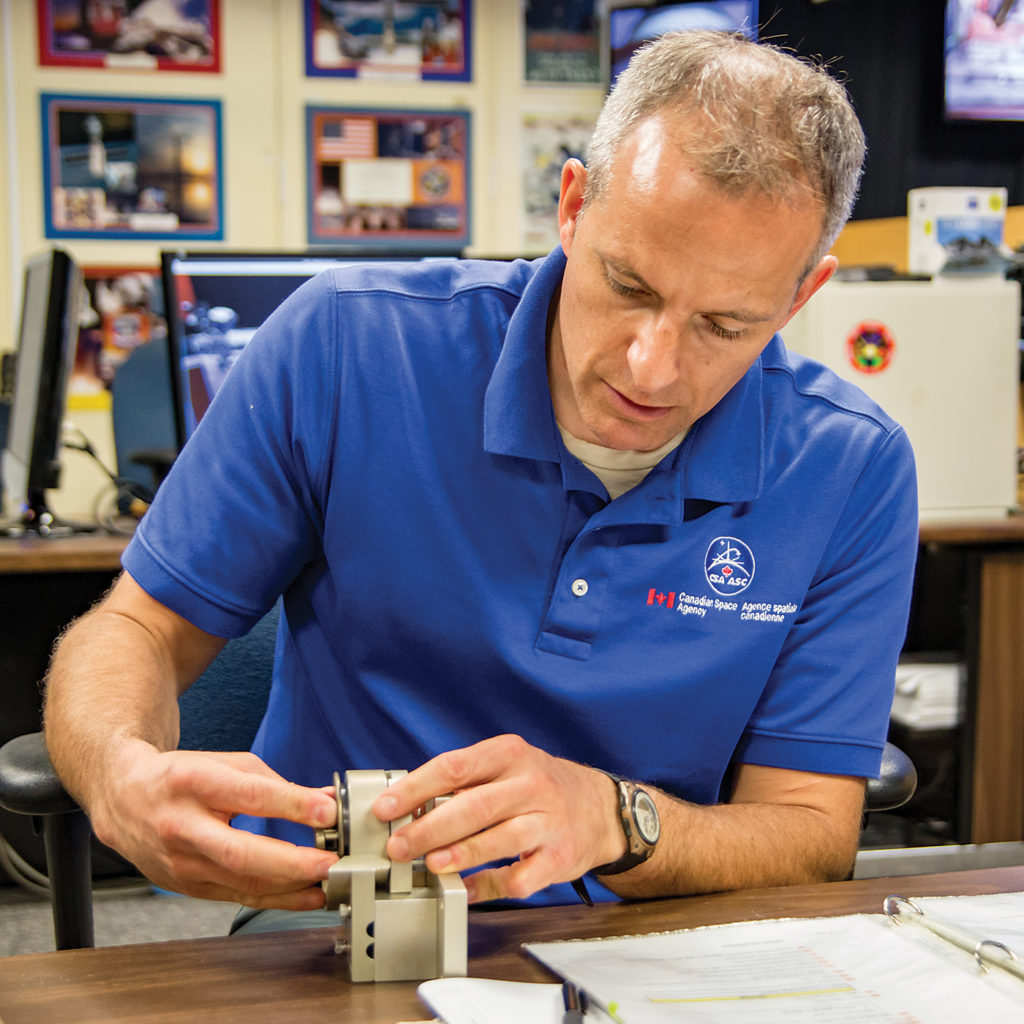

Selected in 2009 by the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) as one of two Canadians to be trained as part of that year’s National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Astronaut Candidate class, David Saint-Jacques is now closing out the final phase of his mission-specific training and is in the midst of completing his final flight-readiness exams; he is preparing to fly on Dec. 20, 2018.

Skies correspondent Sean Costello, in conjunction with SpaceFlightInsider.com, has been covering the professional development of Saint-Jacques and others within the CSA since 2011, tracking Canada’s progress and investments in critical science and health research. In the following report, Costello takes us behind closed doors and into restricted operational areas to learn from instructors, program managers and CSA leaders about all that goes into the preparation of a mission-ready Canadian astronaut.

From a “Canadians in space” perspective, Canada has a strong track record of selecting, preparing and flying some pretty impressive astronauts. From our nation’s first astronaut to fly, the Hon. Marc Garneau (now Minister of Transport) through to our current Governor General, the Rt. Hon. Julie Payette, a total of eight Canadians have flown 16 different missions. Most recently, Col Chris Hadfield (retired, Royal Canadian Air Force) flew to new heights as the first Canadian commander of the International Space Station (ISS), launching aboard a Russian Soyuz capsule in December 2012.

During Hadfield’s five-month mission, he and the CSA made what many would call a science out of creating and sharing a unique mix of engaging photos, informative tweets and entertaining videos about the Earth, space, science and of course–most memorably through his recording of a cover of David Bowie’s “Space Oddity”–music.

But at the core of his mission and efforts, Hadfield was predominantly focused on working through his complex list of medical and scientific research tasks, as well as performing his required station commander duties, all in conjunction with Mission Control in Texas.

It raises the question: How can one person become so well trained and prepared to accomplish so much, especially when they are so physically isolated and separated from the wealth of common resources available to folks still on the ground?

During visits to Johnson Space Center, Baikonur Cosmodrome, Roscosmos Mission Control and some Canadian locations, a clear picture emerged of a typical Canadian astronaut’s path to the stars.

Shaping a future candidate

In the pre-applicant phase, would-be astronauts are actively defining themselves through their studies, their career development and other goal-oriented, personal growth activities. While some lines of study might clearly relate to the astro-sciences, other perfectly appropriate fields include those focusing on science, engineering or medicine–as long as candidates follow their passion and establish a pattern of successful learning and retention of complex material.

Ultimately, that is what selection boards are concerned with; that, and evidence of some highly valuable personal qualities such as resourcefulness, good judgment and a sense of teamwork.

Assumptions that astronaut candidates need to be serving in the military or already be a licensed pilot in order to qualify are incorrect.

Speaking of Saint-Jacques, Edward Tabarah, head of the Canadian Astronaut Corps, told Skies: “David had never flown an airplane when we hired him, but he came up to speed very, very rapidly. He started with an instructor, then he soloed, then he got his IFR [instrument rating].

He acquired that additional skill, but he came to us having already earned a PhD in astrophysics, having worked in astrophysics in Japan [in Japanese, having learned the language], and then switching directions, by becoming a physician–a medical doctor working in the North, in isolated areas. Obviously, he had enough ‘right stuff’ without having to be a pilot.”

Applying and interviewing

During an astronaut recruitment campaign (Canada has held four to date), would-be candidates begin the selection phase by completing and submitting very thorough application packages, detailing such information as their school and professional work history, very specific health and fitness information, as well as the applicant’s personal thoughts and motivations associated with their application.

During the selection phase, which typically takes close to a full year, candidates are subjected to great scrutiny, ensuring that only the strongest, mentally and physically speaking, will advance. For reference, during the last two campaigns in 2009 and 2017 (each of which were held to find two candidates), the CSA received more than 5,300 and 3,700 applications respectively

So, what is the key to advancement during this phase? Candidates must show they can learn quickly and apply the knowledge practically.

“The robotics course itself is over two weeks in length, but within six hours we’re able to give [potential candidates] a classroom and an activity and test them on fairly difficult tasks,” said Tabarah. “That, to me, gives me the confidence that they will succeed in the robotics training. We’re not teaching the robotics now; we’re just making sure they have what it takes to do the mental gymnastics to be able to excel in the robotics training.”

Hired! Time to begin your training

Once selected and hired, astronaut candidates have a few months to make the necessary arrangements for transitioning to their new lives and career, eventually making their way down to Houston, Texas. All Canadian, American and Japanese astronaut candidates are required to live near the Johnson Space Center (JSC) training facilities, while European Space Agency (ESA) and Russian trainees live and train overseas, visiting JSC as required.

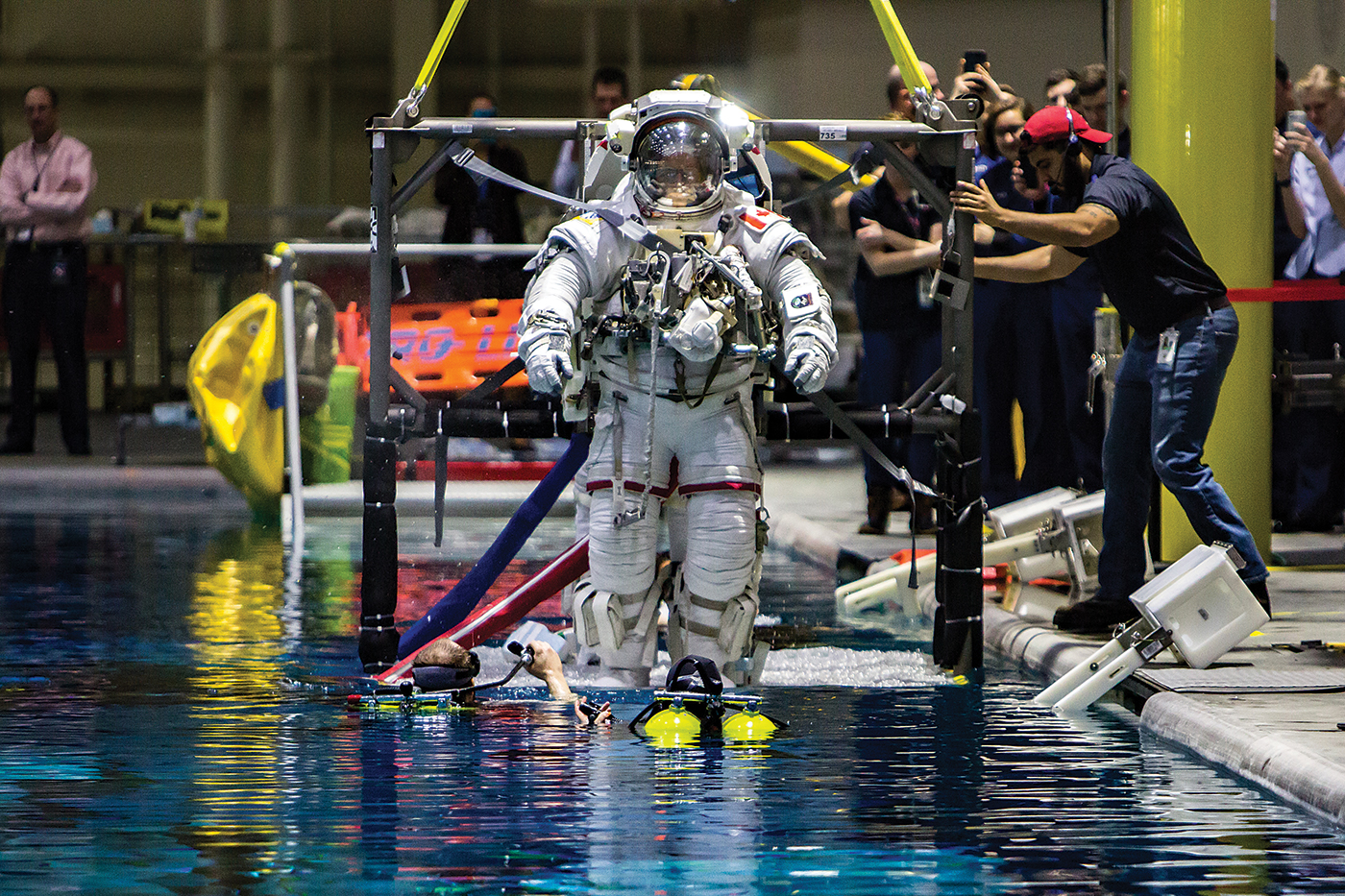

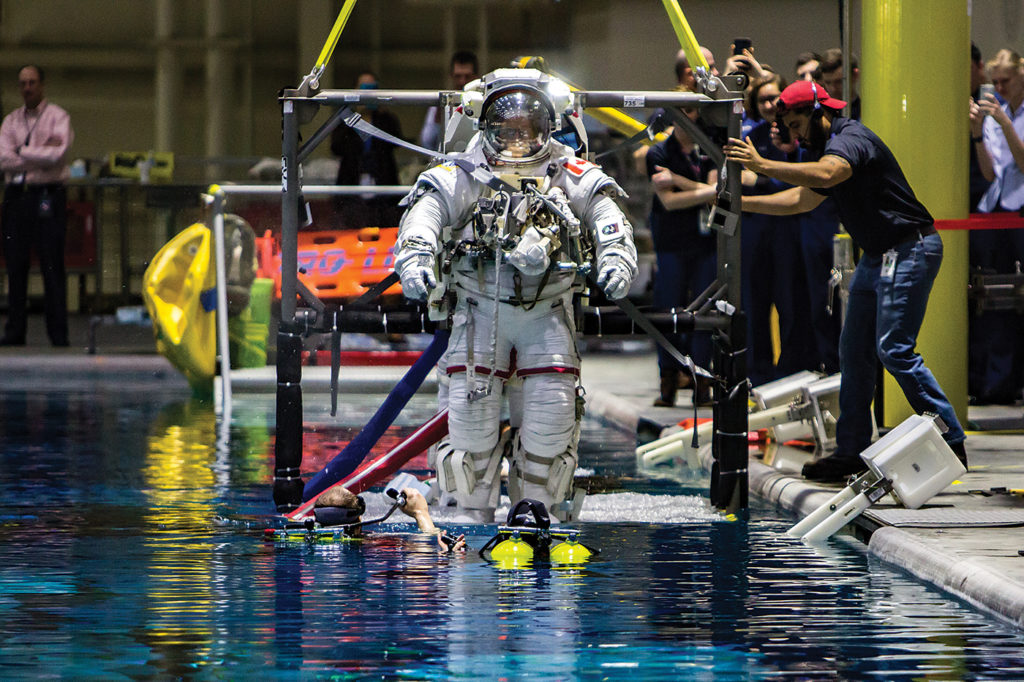

lowered into the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory for extra-vehicular activity (EVA) training. Sean Costello Photo

Following the May 2009 CSA announcement confirming Saint-Jacques and fellow classmate Jeremy Hansen as the successful candidates, they joined three Japanese and nine American candidates to form a 14-person international class, nicknamed “The Chumps.” This class was NASA’s 20th astronaut candidate group.

At this stage, Tabarah explained, a modern-day astronaut candidate is expected to complete two years of basic training to bring all candidates to the same level.

“We give them language training, EVA (extra-vehicular activity, or spacewalk) training, robotics training–but there’s an awful lot of other training as well, like survival training and pilot training,” he said.

“They all pilot the T-38 [Talon] jet, but we also give them private pilot training because although we’re not flying a shuttle anymore, we feel that pilot training is real. Your decisions have consequences. It’s very operational, it’s very much rooted in good communication, being good at following procedures, attention to detail, hand-eye co-ordination–all of those good things that will serve you in your astronaut training and in being a good, effective crew member.”

According to CSA astronaut and RCAF Col Jeremy Hansen, class supervisor for NASA’s Astronaut Class of 2017 (including Canadian candidates Joshua Kutryk and Jenni Sidey-Gibbons), this is also when the candidates get their first exposure to the ISS partner agency properties.

“They won’t all go as one group, but they will all go to do what we call their pre-assignment training in Japan (for the Kibo module), in Germany for the ESA (Columbus) module, and at the CSA in St. Hubert (Montreal) for Canadarm2 training, for robotics training.”

Your mission: Continuous learning as you await ‘the call’

Following graduation, successful candidates are now considered mission-assignable astronauts. Two years into their new career, it is at this stage that one could conceivably be tasked with preparing to fly a specific mission, although it is much more likely that they will be assigned a support role within the space program. There, they will continue to develop their skills, being challenged to grow and work in international teams as they will when they fly aboard the ISS.

For Saint-Jacques, this phase of astronaut development lasted five years, during which time he was very active with additional training and duties, including participation in different Earth-based analogous training expeditions, including the underwater NEEMO 15 mission and the underground CAVES 2013 mission.

According to Hansen, the importance of these expeditionary missions cannot be overstated: “We’re developing astronauts to become explorers by exploring here on Earth, but we are also leveraging these Earth exploration opportunities to exercise how we would explore the lunar surface, or even Mars.”

Congratulations, you’re mission assigned!

Due to the vast amount of preparation and mission-specific training which must occur prior to launch day, the announcement that an astronaut has been mission-assigned usually comes some 30 to 36 months ahead of their flight.

In the case of Saint-Jacques, his assignment was shared with the world on May 16, 2016, at the Canada Aviation and Space Museum. His training began that August.

“Today, I stand on the shoulders of all the astronauts who came before me,” Saint-Jacques said moments after the announcement. “They inspired me–they were my role models. They sparked my curiosity about space and made me want to experience space flight for myself. Space exploration is the next step for humanity, and I am proud to be part of it. I would like to thank the Canadian Space Agency for giving me this incredible opportunity. I am humbled to represent Canada on this mission and promise to give it my very best.”

Mission training: You only thought you knew what busy was…

Mission-specific training is the next chapter in every astronaut’s journey to the stars, and it’s a complex and very tightly choreographed ballet of learning and practical simulations. In addition to preparing for the work and science that they will be performing on station, astronauts also need to prepare for healthy living in microgravity, including training on specialized strength-training equipment, as well as learning everything that one would need to know in order to maintain and operate their football-field sized orbiting home, all while travelling at 27,000-plus kilometres per hour and at an altitude of some 400 kilometres.

Sitting with Skies for an onsite interview in Baikonur, Kazakhstan, Tabarah explained the complexity of the coordinating efforts: “Training happens in all five partner countries; mostly in Houston at JSC, but also in Tsukuba, Japan; Cologne, Germany; Star City in Russia and of course at CSA headquarters in St. Hubert.”

When asked about the approach to planning and scheduling, Tabarah continued, “What we do is script basically all the training for the entire 26 months (of mission-specific training) and we just divide by week; these weeks are in the U.S., then you go to Russia. On your way to Russia, sometimes you’ll go to Europe; occasionally we give them a week of vacation.”

Taking a moment to expand on the human aspect of the training, Tabarah was quick to point out that the CSA recognizes that the astronaut is not the only person impacted by the heavy demands.

“You never want to send someone to Russia for a week and then straight back to the U.S. We’re conscious of the jet lag and all of the effects of changing time zones, but we are also conscious of the family life. David has three very young children; although he has a very capable spouse, the children don’t understand that their father is gone for a long time, shows up and then he is soon gone again–so we are very conscious to try to minimize the impact of the schedule.”

Pre-launch: Bridging the gap between your future and the past

Following the bulk of an astronaut’s mission-specific workups, pre-launch activities begin to take centre stage. As all ISS crew members currently fly to orbit in Russian Soyuz MS spacecraft, much of this time is spent in Star City, just outside Moscow.

remained quarantined behind glass. Sean Costello Photo

The Russian State Commission evaluates the assembled crew as they perform fully-suited launch and landing simulations, injecting challenges to gauge their readiness to address the many contingencies which may appear during flight. Based on his experience and training, Saint-Jacques was assigned to fly as Flight Engineer 1, the co-pilot of the Soyuz capsule, colloquially referred to as the “left-seater.”

Not all pre-launch activities are technical in nature; crewed Russian launches are always preceded by a number of traditional cultural ceremonies and activities, from the planting of a tree alongside another similarly planted by Yuri Gagarin (the first human to fly to space), to the launcher, crew and families being blessed by a Russian Orthodox priest.

During the pre-flight press conference and family visits, both the prime (flying) crew and the backup crew are seated behind a glass wall, part of their two-week quarantine period. They are permitted outside, but three metres is the typical buffer maintained between crew members and non-quarantined individuals.

Two days prior to launch, the assembled launcher is rolled out to the launch pad and raised into position. The backup crew attends and witnesses these events, both to learn from the experience as well as to report back to the prime crew on the progress of their ship; it is considered bad luck for the prime crew to watch these proceedings themselves.

As Saint-Jacques, a member of the backup crew for the June 2018 Soyuz MS-09 launch, stood in quarantine watching the prime crew’s Soyuz roll out, he shared some thoughts on becoming one with his crew-mates.

“This is an interesting time for us to be here as a crew,” he said. “We’ve had a lot of time together, training in Star City. We’ve already become ‘one’ technically; we’re like one machine controlling the spacecraft, but all the time that we’ve spent here in isolation, it’s helped us form more personal bonds. This is a little glimpse of what our life will be like on orbit, when we’re actually roommates!”

Launch day: Your flight is now boarding

Finally, it’s the day they’ve been dreaming of and working toward.

Following a joint crew breakfast and the autographing of their room doors at the Cosmonaut Hotel, astronauts walk to waiting buses while being serenaded by the classic Russian song, Trava U Doma.

Prime crew on one bus, backup crew on another, it’s off to building 254 for suit-up and pressure checks. Following some final terrestrial words with loved ones (still through glass), the prime crew marches out to present themselves to the State commission, obtaining final permission to fly.

Standing with Saint-Jacques at the June 2018 launch, just 1,400 metres south of the now-crewed Soyuz, his mind was clearly following along the checklists he’s learned during training. As the countdown clock ticked down, he mused, “For me, it’s a very personal moment, because I know and love these people. I know exactly where they are in their training; I know exactly what they’re doing right now. I can imagine myself in their shoes, right now.

“I think, in their hearts, the mission has already started, because now the last helper from the launch platform team has left the spacecraft, the hatch is closed, they’re strapped in, power is up and they’re already working their procedures. In their hearts and minds, they’ve already started their mission to the International Space Station.”

Saint-Jacques’ inaugural mission, Expedition 58/59, is scheduled to launch on Dec. 20, 2018. Readers wishing to follow the mission’s progress or learn more about the science which Saint-Jacques will be performing on orbit can visit the Canadian Space Agency’s website.