Estimated reading time 9 minutes, 15 seconds.

Greater Montreal is home to more than 200 aerospace companies. Ranging from small private outfits to massive corporations with operations around the globe, its residents together represent one of the world’s most important aerospace nodes.

Examples of its leading players include Airbus, Bell, Bombardier, CAE and Pratt & Whitney Canada (P&WC). A jewel in this industrial crown is the latter’s Mirabel Aerospace Centre (MAC).

Located at Montreal-Mirabel International Airport, 40 kilometres (24 miles) northwest of Montreal, it is comprised of a leading-edge turbofan engine manufacturing facility and the global base for P&W’s turbine engine flight testing.

Background

Pratt & Whitney Canada has long had a substantial presence in the Montreal area. Incorporated in November 1928, it was established on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River at Longueuil. Ninety years later, P&WC’s head office and primary manufacturing plant remain there.

In March 2004, Bombardier began to evaluate the possibility of creating a new generation airliner to replace the thousands of aging Boeing 737s and McDonnell Douglas DC-9s that were in service. The key selling point of such an aircraft would be its reduced operating costs. A large contributor to that improved economic performance would be more fuel-efficient engines. Subsequent to a thorough analysis, Bombardier selected Pratt & Whitney to be the sole engine supplier for the new airliner.

The engine was the new PW1524G geared turbofan. The aircraft would evolve into the C Series family with two models-the 100-to-130-seat CS100 and the 130-to-160-seat CS300.

With P&WC onboard the Bombardier program, a decision had to be made about where the new engine would be produced. While its Longueuil facilities may have provided the required capacity to start out, P&WC wanted to develop a clean sheet facility that utilized the latest manufacturing methodologies, known as lean manufacturing. Around this time, P&WC was upgrading its fleet of flying test beds (FTBs) from a pair of Boeing 720s to a pair of rare Boeing 747SPs.

In late October 2004, the expansive airfield at nearby Mirabel became a cargo-oriented airport with the cessation of passenger services. Airport and government authorities wanted to stimulate Mirabel’s economy by attracting corporations that would benefit from being onsite. Bombardier Aerospace was already producing its successful family of regional jets (CRJ200, CRJ700 and CRJ900) there, so when it announced that the C Series models would be built there another piece of the puzzle fell into place for P&WC.

Furthermore, Mirabel’s long runways and lack of air traffic congestion made it an ideal base for P&W’s FTB operations. The availability of suitable real estate for both a hangar complex and a new manufacturing plant was another positive. In addition, the new complex would be located within the Montreal Foreign Trade Zone at Mirabel. As such, it would qualify for special tax-related benefits. Finally, the provision of supplemental funding of approximately $150 million towards construction and equipment costs from the Province of Quebec was granted.

In October 2008, the go-ahead was given to develop the MAC in two phases. The first phase was inaugurated in October 2010 and contained P&W’s global flight test operations base. Its large two-bay hangar houses the pair of specially modified 747SPs.

The MAC’s second phase was officially opened in May 2011. It contains the manufacturing plant and two large jet engine test cells. Each cell is 92 metres (300 feet) long and 35 metres (115 feet) tall. They can accommodate engines that produce up to 35,000 pounds of thrust.

The MAC’s total footprint of 27,800 metres (300,000 square feet) also includes machine, paint and metal-working shops; administrative offices; a medical centre; and a kitchen/cafeteria. The entire complex was designed to meet Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) standards. For example, it has a large passive solar wall, energy efficient lighting and expansive glass panels that enhance the use of natural light. The total cost of the development was approximately $600 million, of which some $90 million was for the first phase.

Given that it was a clean sheet design, P&WC wanted the manufacturing facility to have “next generation” capabilities. This meant the use of advanced manufacturing technologies and the implementation of the latest production principles to ensure efficiency, flawless quality and a perfect environment, health and safety (EH&S) culture for its employees.

To meet these objectives, P&WC studied the manufacturing operations of more than two dozen major corporations across a broad range of industries to determine the best practices employed around the world. Suppliers were then asked to advise on the design and operating methods of the required equipment. Production processes were then simulated and validated before being installed.

Equipment is only half of the production equation. Human talent is the other. An achievement-oriented culture among the employees is mandatory. The company worked with union managers and aerospace educational institutions to define job descriptions, candidate identification guidelines and employee selection methods. In addition, training programs were developed.

Evolving production process

The traditional manufacture of a given product typically involved hundreds of suppliers that provided thousands of parts for that product.

These parts were held in inventory by the manufacturer, then were delivered as required for final assembly. Today, tens of suppliers provide tens of modular components (each consisting of hundreds of pre-assembly parts) for the same product. As a result, the manufacturer has significantly reduced parts inventories, has fewer production responsibilities and shorter assembly times.

Some companies have progressed further by introducing so-called lean manufacturing techniques. A key tenet of lean manufacturing is that production levels of a particular product shift as customer demand dictates. As a result, the time to produce each unit is reduced, inventory levels of parts and finished goods decline, productivity increases and the utilization of assets (plant and equipment) is enhanced. This methodology is said to result in a 20 per cent improvement in production output compared to the traditional process.

Manufacturing at the MAC

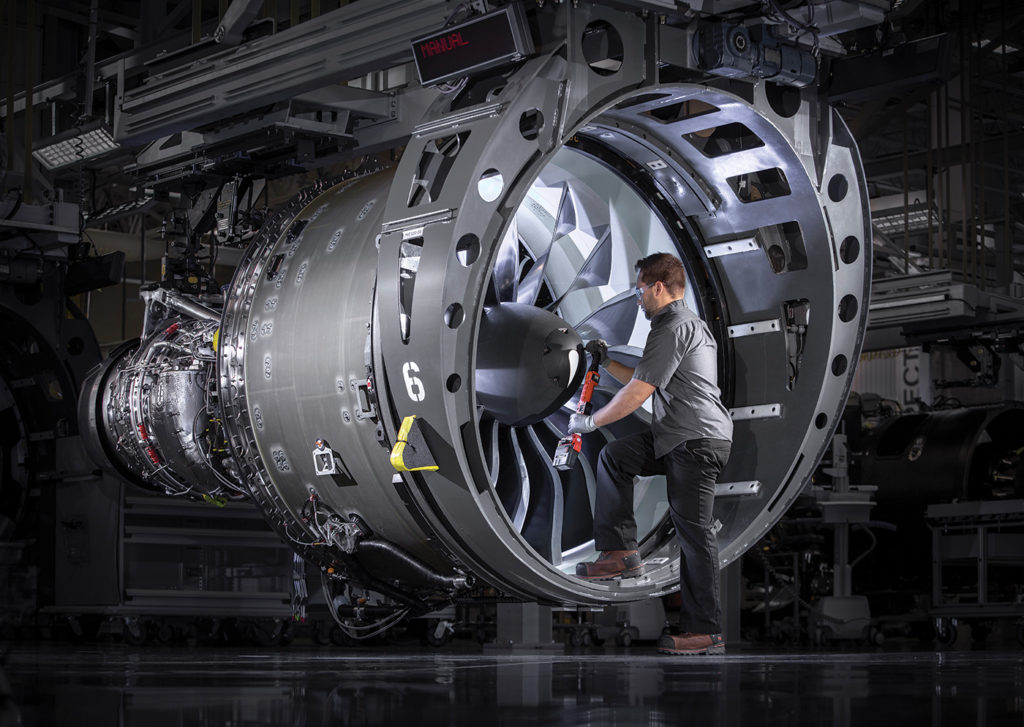

Instead of being assembled at fixed workstations, the engines at the MAC proceed along an overhead assembly line that moves according to programmed pitch increments. This pre-set speed can be modified as needed to deal with any production-related issues on the line.

As it progresses down the line, each engine is rotated so that assembly personnel do not have to climb above it when installing components. This greatly reduces the potential for injuries. The specially trained workers are multiskilled, thereby improving shop floor productivity.

The work environment at the MAC is different than most workplaces, as it is paperless. Communication with the operators on the floor is done via wireless workstations. Information such as the daily task list, specific assembly instructions and production status is provided on screens rather than sheets of paper.

The MAC’s assembly line was designed to significantly reduce the movement of parts and components on the shop floor during the manufacturing process. Tools and parts required by personnel are delivered to their workstations by robotic vehicles. Furthermore, it is a clean space. Jewellery of any type, personal electronic devices (including cell phones), food and beverages are not allowed on the production line. This eliminates the risk of accidental damage to or contamination of an engine. It also removes potential distractions from the tasks at hand. All this is to ensure that each engine is completed without any quality or performance issues.

Once an engine is completed, it has to be inspected and then tested prior to delivery to the customer. After a visual inspection, each engine is transported by a laser-guided mobile robot (automated guided vehicle or AGV) from the assembly line to one of the two engine test cells. There it has test instrumentation fitted to it prior to entering the cell. Once it has undergone a series of rigorous tests, it is prepared for shipment to the customer.

The MAC’s manufacturing facility currently has approximately 300 employees. Only a small number of those are on the shop floor at any given time. When Skies visited the facility, a survey of the production line from a boardroom above revealed a very clean and efficient work environment. The plant operates seven days a week, with two shifts every weekday and a single shift daily during the weekends.

Marc Gravel, the MAC’s director, took obvious pride in the performance of his team. When asked how he screens potential hires, he explained that strict hiring criteria are used to vet candidates. This includes theoretical exams, practical situational reviews, psychometric tests and face-to-face interviews. The latter are used to determine how an individual would react in a challenging situation. Clearly, academic achievement alone does not guarantee a position on this team.

Future prospects

When asked about the future of the MAC’s production business, Gravel noted that the plant currently produces approximately 250 engines per year. The facility has the capacity to double that output. He said that such an expansion would be dependent on two factors.

First, given the growing demand for jet engines that are more fuel efficient, produce lower emissions and are quieter, P&WC’s current products are very well positioned. Going forward, there may be additional models as market demand dictates.

Secondly, the four families of engines currently produced at Mirabel are associated with aircraft models that have either recently entered service or are still in the process of being certified.

Pratt & Whitney’s decision to develop the Mirabel Aerospace Centre has proven to have been a fruitful exercise. Thanks to its leading-edge facilities and its highly motivated team members, the MAC will likely achieve impressive results going forward.

These pictures are amazing!!!